The Tiger Project Team is off and running. Systems architecture drawings and user interface designs paper the walls of the Fieldstone Toyota conference room. A new designer, Allison, sits at a desk in the corner. Everyone squeezed closer together to make room. As she works on her computer, Allison looks uncomfortable. It’s now really tight in here.

Your first big decision after the downsizing was to charter the Tiger Project Team. It seems to be paying off. The team is hard at work, and you’re encouraged by its progress. Joe emerged as a solid team leader. All team members are fully engaged; development proceeds apace. Even though it seems that every meeting features at least one big argument, the team’s work output is steady, and the emerging CRM design looks sound.

Your second big decision was what to do yourself.

You chose four personal priorities. One, to raise the seed round — your existing investors put up $600K, but you needed to find $400K more. Two, to support the handful of dealers who chose to remain on your price quote product. Three, to engage more deeply in the marketplace. Four, most crucially, to maintain close oversight of the Tiger Project Team.

Four months ago, you accomplished the funding challenge, the first of your priorities. Two new investors put up $200K each, bringing the round to $1M as planned. With your current $100K burn, you have enough money for another seven months — until at least April of next year. You were pleasantly surprised to find that most of your original price quote customers figured out how to work within the constraints of your product, and it’s working well enough for eighteen of them to stay on board. You’re not trying to sell new customers. A few reached out, but you respectfully declined. Except for Bill (the only employee supporting existing customers), everyone’s focus is on building the new CRM product.

After securing the seed round, you met with operations and marketing executives at Toyota, General Motors, Ford, Subaru, Mazda, and Volkswagen. BMW and Honda meetings are coming soon. In each of these meetings, you sought validation that price transparency is indeed a strategic imperative for manufacturers. You received consistent validation that it is. Furthermore, these manufacturer executives demonstrated an interest in SparkLight’s pursuit of a next generation CRM. They openly shared their research, which confirmed that consumers increasingly seek a mobile-friendly car buying and car servicing experience.

But another theme emerged in these conversations. Social media has become a brand killer for both manufacturers and dealers. And dealers, in particular, are doing a lousy job managing their own reputations. A number of the execs you spoke with wondered whether a next-generation CRM could help. Could negative social media posts be flagged and reported to dealers via the CRM? Could simple workflows be developed so that these negative posts received rapid apologetic or appreciative responses? Could social media reputation analytics be cleanly presented that provide insights not just for dealers but also for manufacturers?

You also met with dealer GMs and dealer group principals. Technology options have exploded. Dealers are drowning in a sea of one-off tools. They confided that the shift to mobile caught them unprepared. Dealers also expressed their frustration with increasingly hard to manage workflows. They don’t need yet another tool. They need one uber communications hub for everything — from sales leads to service communications to social media reputation management. The problem is that such a hub doesn’t exist.

This feedback from manufacturers and dealers galvanized you. Your vision is more fit and trim, as are your ambitions for the Tiger Project. But Joe resists hearing about it. To Joe, these insights feel like scope creep. He can barely imagine getting a robust mobile-centric sales CRM solution out the door by year end; this uber communications hub sounds overwhelmingly expansive in reach. The team is too small and the time too short to do everything. He argues for radical prioritization.

. . .

A team is a tool to do mighty things.

A team brought Apollo 13 back to earth. A team built the Macintosh. A team led the Darwin Project that saved Ben Horowitz’ OpsWare. But too often, leaders use the word “team” to designate any group of people who work together. Functional groups, executive groups, and workflow groups are routinely named teams. However, a collection of workers is no more a team than a flock of sheep, a gaggle of geese or a murder of crows. The word “team” must be earned.

A real team is a sophisticated problem-solving tool. It meets a high standard in both attributes and performance. To create a team is a significant investment. It makes sense to deploy only when the assignment of individual responsibility is insufficient, given the task at hand.

Whenever there is a task to complete, a leader must assign someone the responsibility to perform it. Depending on the task, there is a continuum of responsibility assignment options, from fully individual to fully collective. As CEO, you might:

- Assign individual responsibility for work to be produced by just one individual

- Assign individual responsibilities to multiple individuals who share similar work inside a functional group

- Assign individual responsibility to functional leaders who coordinate activities as an executive group

- Assign individual responsibilities to multiple individuals who comprise a workflow group

- Assign collective responsibility to a team for a work product

When the desired output is primarily dependent on individual action, a leader assigns individual responsibility. Whenever this occurs, superior and subordinate share a straightforward accountability relationship. Expectations are made clear, progress is monitored, and feedback is given. For instance, most of the activity and outcome expectations for CFOs, engineering VPs, marketing directors, salespeople, customer success managers, growth marketers, product managers, dev ops engineers, financial analysts, and data scientists can all be managed perfectly well via assignment of individual responsibility.

A functional group — such as the sales department, customer success department, or engineering department — is usually not a team. It is a collection of people executing a function. For example, eight account executives, each working on a list of named accounts, do not make up a team.

The executive group is usually not a team. The level of mutual accountability, the degree of commitment to a common approach, and the clarity and specificity of the shared goals typically fall short of the “team” threshold. Most often, the executive group is a collection of functional leaders who share information, align on strategy, identify gaps between desired and current performance, debate priorities and the allocation of resources, and identify functional handoff issues to resolve. But the real work that results from this coordination is left to each of the functional leaders, acting on their own.

Operations are defined by workflows. When collaboration is required for a workflow to run effectively, the collaborators comprise a workflow group. In a workflow group, each individual is assigned a set of individual responsibilities, including the responsibility to ensure close coordination and clean handoffs at the nexus between roles. For instance in marketing, the brand marketers, growth marketers, and product marketers must work together to execute a standard messaging schema anchored in a single brand identity. Similarly, Marketing and Sales VPs must work together to ensure smooth transmission of leads from marketing to sales. And sales development reps (SDRs) must set up qualified appointments for account executives, who need to show up prepared. All three of these are examples of workflow groups. A workflow group may exist inside a functional department, or between functional departments — such as between marketing and sales.

Workflow groups are usually not teams.

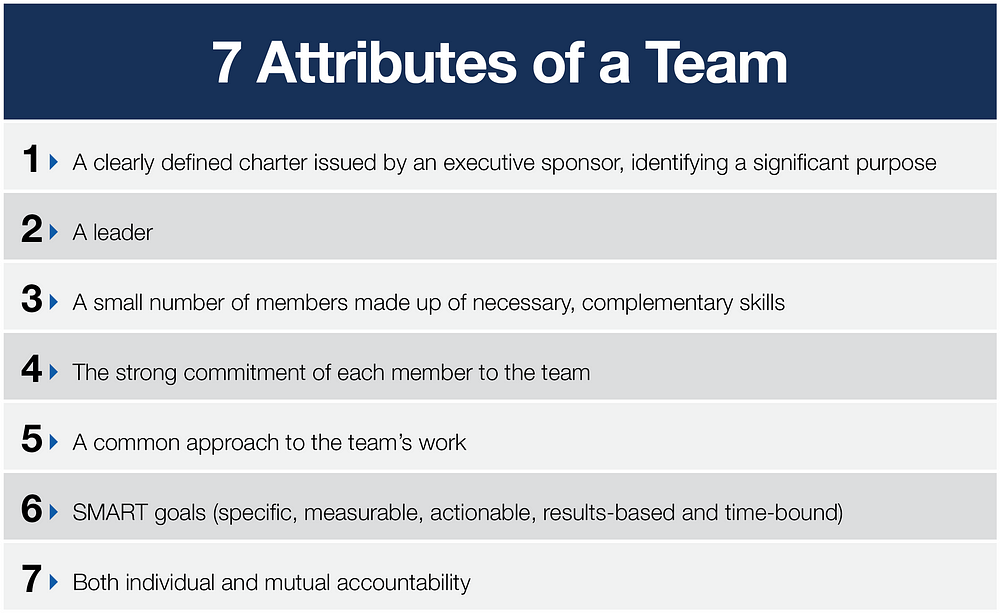

Real teams are different. They earn the word “team” by exhibiting seven key attributes:

There are two types of teams: standing and project based.

A standing team comprises people whose primary jobs are mutually interdependent, such as a workflow group or, rarely, an executive group. For these members, 100% of their time is on the team, because it’s their jobs. Workflow groups become teams only when a leader assigns an aggressive, time-bounded goal to the group, tied to a significant purpose. For example, a goal may be to meet a critical performance outcome or to conduct a substantial workflow redesign. Most functional and workflow groups do not rise to the “team” standard.

A project-based team draws membership from anywhere in the organization. It too is time-bounded. A clear indicator of whether or not the group rises to the “team” threshold is if all members have allocated at least 30% of their time to the team. If it’s a team, membership is a major priority.

Jon Katzenbach and Douglas Smith in their book, The Wisdom of Teams, put it this way: “Groups become teams through disciplined action. They share a common purpose, agree on performance goals, define a common working approach, develop high levels of complementary skills and hold themselves mutually accountable for results.”¹

Real teams deliver multidimensional, comprehensive work outputs that yield significant business impact. They also serve as powerful developers of talent. Big leaps in personal growth can be experienced by simply being the member of a successful team. The member of one such team becomes prepared to be the leader of the next.

In the beginning, your founding team shows all the hallmarks of a real team. There’s a significant purpose, clear goals (prove traction and get funded), a leader, membership with complementary skills, high levels of commitment, and strong mutual accountability. But as a company scales, the number of employees grows. Levels are added, and roles become specialized. Inevitably, the founding team breaks down.

The loss of the founding team sneaks up on you. It formed so naturally and was a defining factor in your early success. But suddenly you realize it’s gone. When that happens — and if you’re successful, it will — you will confront the fact that from this point forward, any future team will be the result of a proactive leadership decision. It won’t just happen. From now on, you will need to think deeply about what problems require a team. And then you’ll need to take the necessary steps to create one.

The creation of a team imposes a sacrifice on day-to-day operations. It is a decision to invest money, time, and human capital in the hope of a meaningful mid or long-term business impact. Actions with immediate reward get deferred. And because there is a wide array of ways that teams can fail, your company is introduced to increased risk. But you take on this risk in the calculation that the team will drive significant positive change in a critical priority area.

While standing teams are created either to chase a major performance milestone or to execute a significant workflow redesign, project teams have more diverse purposes, such as:

- Make strategic recommendations (task force)

- Build a new organizational unit

- Create and launch a new product

- Fix a current product

- Lead a strategic pivot

- Enter a new market

- Integrate an acquired company

- Negotiate and integrate a business partnership

- Plan and execute a significant step in the scaling of the revenue engine

- Plan and execute a financing round

- Plan and execute a reorganization or downsizing

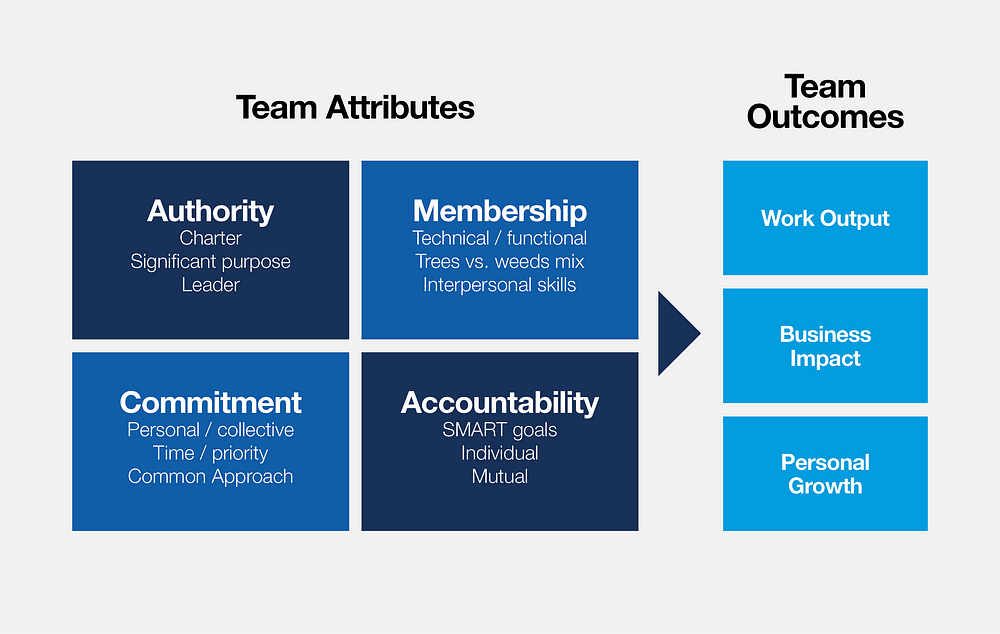

While the outcomes of standing and project teams vary, you must consider the same set of team attributes in creating and managing a winning team, as shown below.

Authority

You start with the team charter. It identifies the team’s purpose, timeframe, leader, and high-level output expectations (defined as SMART goals).

There is an executive sponsor — not a member of the team — to track team progress and coach the team leader. For a team to thrive, the executive sponsor must give the team space, avoiding the temptation to micromanage. Oversight is essential; done well, it increases team leverage. Micromanagement kills it.

Your selection of the team leader is perhaps the single most significant choice you will make. The leader must have passion for the team’s purpose, domain expertise, and strong interpersonal skills. The leader will be the primary thought leader, building a thesis for the project or standing team’s work output. Leaders also co-create the plan for how the team’s work will be accomplished, socialized, and finalized.

Teams are often comprised of members from multiple functional departments. Members often have formal reporting relationships to people other than the team leader. So the team leader’s capacity to exert influence — drawing upon a combination of widely acknowledged domain expertise and interpersonal effectiveness — is critical. A strong team leader will recognize the role is not just to assign work to others. Every effective team leader shares fully in the real work of the team.

Membership

In considering team membership, ponder the desired work output.

Are you envisioning a brand new company direction? Are you optimizing a workflow? Or are you completing a specific project, such as the opening of a large remote office or penetration of a new market? Membership must fit the mission.

Transformational change involves seven dimensions. Incremental change involves just some of them. Given your team purpose, consider which dimensions are required. These dimensions will point you to the competencies you must include in team membership.

Here are the dimensions of change:

- Envision (data-driven researchers, creative thinkers, senior operators)

- Architect (detail oriented workflow designers, project planners, senior operators, workflow participants)

- Build (workflow designers, project managers)

- Implement (project managers, operators, workflow participants)

- Stabilize (operators, workflow participants)

- Optimize (operators, workflow participants)

- Scale (operators, workflow participants)

In selecting team members, consider cognitive diversity. Research by Suzanne Vickberg and Kim Christfort published in Harvard Business Review concluded that there are four dominant styles in team members:²

- Pioneers — spark energy and imagination; value possibilities; like going with the gut; big picture

- Guardians — value stability; bring rigor; pragmatic; risk averse

- Drivers — rise to a challenge; create momentum; win at all costs; problems are black and white

- Integrators — seek to bring people together; look for consensus; see most things as relative

Team conflict most often arises between members with opposite profiles (i.e., pioneers vs. guardians and drivers vs. integrators). But diversity of perspectives also can increase the quality of decision making, balancing change and stability, risk and reward.

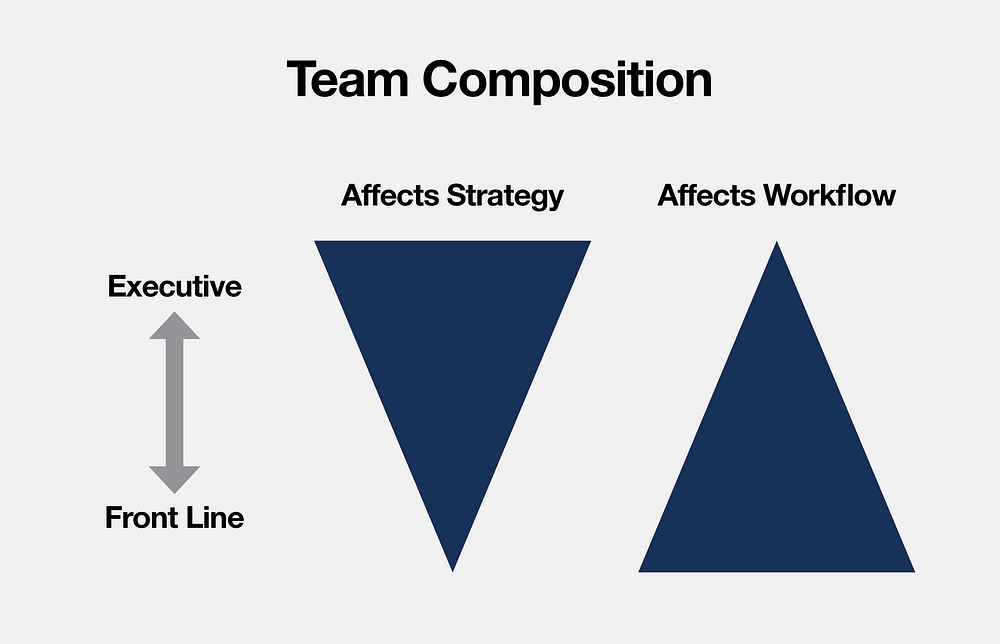

Given the task, what types of critical thinking, creative problem solving, project management, analytical, strategic, tactical, and detail oriented data-driven skills are required? A mix of “trees” people (see the big picture) and “weeds” people (detail oriented, tactical) often is important. And for many teams, multi-level participation is required. The requirements of the task always drive team composition. For instance, in workflow redesign projects, individual contributor participation almost always makes sense:

Since teams can be brought to their knees by one overbearing boor who dominates every conversation, make sure every member possesses basic interpersonal competency. Mutual respect, and the capacity to both listen and advocate are fundamental.

Teams are increasingly diverse, dispersed, digital, and dynamic. Diversity in gender, ethnicity, background, personality, technical skills, and problem-solving approaches opens the door to multidimensional and nuanced solutions. In fact, diversity is often a key factor in the startling innovation breakthroughs seen with the highest performing teams. But it also increases gridlock risk. To mitigate this risk, a strong team leader able to exercise sufficient interpersonal influence is pivotal to a successful team.

It is said that teams form, then storm, and then norm before they can perform. It’s true. Along the way, each team member makes judgments about the competency and commitment of the other members of the team. Weak links are quickly identified and resented. On high performing teams, the skills and capabilities of each member are deeply respected by each other member. Underperformers are not welcome. Strong teams are made of strong members.

Commitment

The commitment to a team is personal.

Team membership is not a side project. It’s a top personal priority. For standing teams, of course, membership is a 100% time commitment. But the commitment must also be to the team’s purpose; each team member must be emotionally invested. For project teams, a member should spend 30% or more of time on team-related work either in meetings or work between meetings.

The commitment to a team is also collective.

Trust doesn’t just happen. It builds through shared experiences, and problems overcome. Team members start by figuring out a common approach to completing the assignment. Agreements must be negotiated concerning the maintenance of confidentiality, willingness to hold each other accountable, and other group norms. The frequency of meetings, the stages of the work, the involvement of subject matter experts at points along the way, and each member’s expected contributions must be agreed. Through these team commitments, individuals sacrifice some independence in return for interdependence. Collective commitments are the headwaters of trust.

But trust becomes genuinely abiding only once the team has overcome significant adversity. Trust is forged in the struggle.

Accountability

Consistent with the charter, the team is accountable for the achievement of SMART goals. There are three layers of accountability.

First, the team leader and executive sponsor share an accountability relationship; the leader must deliver regular progress reports, and the executive sponsor must test, critique, and challenge. Next, each member of the team shares an accountability relationship with the leader. Members must complete their work and provide regular updates to the leader, and the leader must test, critique, and challenge.

In high performing teams, accountability relationships are also mutual. Each member holds each other member mutually accountable. Doing so raises the bar on performance. Good work is not good enough. Only outstanding work will do. All members are so committed to the team that they seek always to deliver their very best work. Profound mutual sacrifice and selflessness define exceptional teams.

The creation of a team is a significant commitment. But when chartered and populated well, teams consistently exceed the output of individuals. Truly transformational innovation almost always emerges from a team, not an individual. Successful teams yield more thoughtful, creative, and nuanced solutions than any one individual could ever conceive. Often, the biggest business challenges are too critical, complex, multidimensional, and cross-functional to be solved any other way.

Should your company be teams driven?

The more significant the change your company must undergo, the more a team-based approach is merited. As CEO you must continuously assess your current state — your market position and operational reality. Where are your competitive threats? What product shortfalls need addressing? What internal bottlenecks are most critical to solve? These questions may well lead you to recognize that you have a significant need for team-driven change.

But the need for teams is just one side of the coin. The other side is capacity. How many people in your organization possess enough team development skill to be a team leader? How many people can you afford to divert into team-based work?

Every team will require an executive sponsor and a team leader; both must be skilled in team management. Furthermore, you must be able to afford the cost to day-to-day work of each member’s involvement on the team. The number of teams you can charter will most likely be bounded more by human capacity constraints than by need.

One thing is sure. Every time you navigate a team from initial charter and launch to a powerful, successful outcome, you increase your company’s team competency and capacity.

. . .

It’s October, and there is a chill in the air.

Progress on CRM development steadily continues, but you wrestle mightily with the scope question. This CRM must be a Swiss army knife for dealers. To create a comprehensive communications hub requires four spokes: robust sales workflow, strong service workflow, social media reputation management, and multi-store analytics (for dealer groups). It’s an overwhelming amount of work. And since each manufacturer has different legacy systems, the integration burden is enormous.

There are two alternative ways to get there. You could go slowly and methodically, fully completing one spoke before moving on to the next. Or you can quickly introduce minimum-viable-product versions of all four spokes, knowing that they will be full of holes and bugs. The latter approach will force you to follow initial release with an extended “whack-a-mole” phase of hole-filling and bug-fixing.

It’s a tough call. The “focus, focus, focus” mantra rings loudly in your ear. But dealers are sick of one-off solutions. They need a hub. One spoke every nine months won’t work. You have to get to “hub” faster.

After multiple contentious dinner meetings with Joe, an agreement emerges. You will initially build just for General Motors dealers, reducing the integration burden. You will roll out the hub in stages, but a 1.0 version will be up and running by end January — lightning speed in technology terms. It’s risky, but it’s the only way to signal to the market that you have the uber communications hub that dealers desire. “Go big or go home,” you say to Joe.

The plan is set. You will launch a mobile-centric, sales-only product targeted to single-point GM dealers under 100 leads a month by January. By early Q2, you will add an analytics dashboard that will support dealer group views (still sales-only). The dashboard will allow you to move up-market to dealer groups but requires that you begin to support integrations for manufacturers beyond GM. By Q3, you will extend into a few basic auto service department CRM features, and by Q4 you will introduce a straightforward social media reputation management tool for responding to social media posts. When launched, none of these four components will be full-featured, but the most important features will be in place. By that time, you should be able to support integrations into all major manufacturers.

At the next weekly meeting with the team, Joe stands by your side. You lay out the challenge in stark terms. “Folks, anyone who knows anything about technology would say that what I’m asking of you is impossible. How can we get a sales CRM out the door and sold to thirty dealers in three months? Impossible. But that’s exactly our challenge. We don’t have enough money to go longer. Our board believes we won’t be able to raise an A round without thirty happy customers on a new CRM, and I think they’re right. So quite simply, we must do the impossible.”

The team stands in a circle around you. Beatrice straightens. Vijaya nods. Sanjay smiles, and there is fire in his eyes. Farook purses his lips and says, “Game on.” Right after the meeting, there is a burst of animated conversation. Beatrice is already offering to add to her plate. Vijaya feeds off the energy and offers up new ideas for how she can contribute. Sanjay just heads back to his computer and starts coding. Farook starts drawing a workflow on the whiteboard. Joe, encouraged by the team’s initial reaction, also notices that Allison, the new designer, seems ruffled by the intensity around her.

Within two weeks, it is clear that Allison isn’t up to the task. She can’t keep up and doesn’t want to work this hard. The team recognizes it first. Then Joe. Then Allison. Less than a month after her start date, she’s gone.

. . .

Notes:

- Jon R. Katzenbach and Douglas K. Smith, The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1993), 14–15.

- Suzanne M. Johnson Vickberg and Kim Christfort, “Pioneers, Drivers, Integrators, and Guardians,” Harvard Business Review, March-April 2017, https://hbr.org/2017/03/the-new-science-of-team-chemistry#pioneers-drivers-integrators-and-guardians.