Leadership is not a cloak thrown over your shoulder. It’s your life.

You are the founding CEO of a thirteen-month-old tech startup, SparkLight Digital. Your decision to start your company with Joe, a buddy of yours from your college days, was ignited by a passion and a vision — hence the name. You couldn’t bear the idea of continuing to work in a cushy nine-to-five corporate job. You needed to be your own boss. You needed the buzz you could get free climbing your way up a cliff of your own creation. You wanted to make an impact on the world.

But what a journey. It’s been gut-punch hard. Five days straight, five hours of sleep a night. Three of you huddle over computers perched on a single Home Depot door-turned-desk in the middle of your apartment. Scattered on the floor lie two pizza boxes littered with half-chewed crusts and empty energy drink cans. Joe has been coding for 18 hours straight — his head just dropped onto the keyboard. Vijaya, the product and user experience expert you hired, is exhausted. You’re down to the last $10K in the bank. You owe $12K to creditors. The rent for your apartment is coming due. Only Vijaya is taking a salary. Both Joe and you have poured all your savings into the company. Nothing left there. The credit cards are maxed out. Everyone’s parents are tapped out. You’ve been scouring LinkedIn for hours, making a list of angel investor prospects to chase. It’s four in the morning, so it’s a bit too early to send the meeting-request InMails. You’ll wait until 7.

. . .

The first task of any entrepreneur is to recruit one or more co-founders. Perhaps no decision is more consequential. You must find one or two people who possess complementary skills to yours. Both you and your co-founders must be wicked smart. You all must have the financial capacity to survive at least a year with no pay. If possible, choose someone you know very well. Someone you’ve worked with before. This reduces risk.

. . .

Thank God there’s a guy who said last week he’s in for $500K. The problem is, you haven’t yet told him your only beta customer wants to cancel. The GM from Toyota of Palo Alto just emailed you last Monday, saying there have been too many bugs and integration issues. His sales team has revolted — they won’t use your product. You camped out at his office for two days and did everything you could to reel him back in, promising to fix everything in a week, but it’s not going to happen. You feel trapped in that dream where a monster is chasing you, and you’re trying to run, but your feet are stuck in the mud. At every turn, each decision feels like life and death, because it is.

The heat of startup life is intense. In the forge, steel either tempers or cracks. Your character informs (and is shaped by) every decision you make. It’s time for a decision — do you tell the investor your only customer has canceled?

Joe’s awake again. It’s 7 AM, and he’s shouting at you. Vijaya has her arms crossed, and she looks like she agrees with Joe. The investor InMails will have to wait. Joe can’t believe you’ve decided to tell the one investor who has bought into the vision that we’ve lost our only customer. He wants you to consider the customer “not lost” until the next billing period. You explain as best you can. As you summon your next point, he swears, throws his hoodie over his head and walks out the door. You’re not sure he’ll come back.

. . .

In the beginning, there is a team. This founding team is the company. It is the essential organizational unit, the archetype for every team your company will create as it scales. It is pure. There is unfettered continuous communication. There’s total flexibility, paired with existential consequences. Because there’s inertia, all forward motion is directly linked to shared initiative. Nothing gets done without sustained effort. All problems are shared problems; most solutions are shared solutions. The authority structure is clear — there’s a leader, and there are followers. Together you achieve the impossible routinely because you have no choice. Everyone pulls their weight. Everyone fights above their weight class. You are a team.

. . .

Even now, your team has a culture. Thirteen months in, your culture is simple: “Total austerity. Total honesty. Total commitment. Never say die.”

. . .

The composition of your founding team is the most crucial decision of all. If you’ve chosen well, each member has job optionality, so you and your vision must compel. You need skill, commitment, and accountability. You need brilliance, courage, passion, and tenacity. These are the necessary things. For at least the first three years, your life will be epic hardship and toil as you wage a relentless battle with panic and despair, broken only occasionally by moments of euphoria. You need people who won’t quit, and who will do whatever it takes. Against all the odds. No matter what.

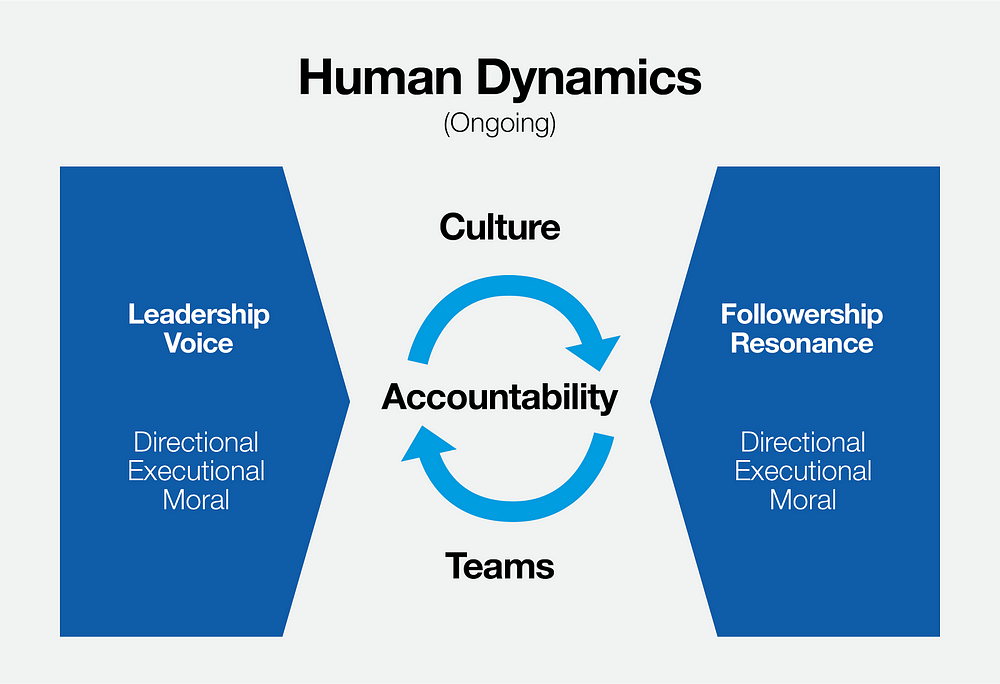

To overcome inertia, leaders project their voice. There is directional voice: “here’s where we’re going.” There’s executional voice: “here’s what matters now, here’s how we’re doing, here’s what you need to fix and here’s when I expect it done.” Depending on the situation, a leader might seek input from one follower, or all, or none. Or she might delegate the decision while never abdicating accountability for it. Both directional voice and executional voice are transactional.

And then there’s moral voice: “I will do the right thing, not the easy thing — and I’ll do it the right way.” Here we see the fruits of courage, caring, and other virtues. Moral voice is transformational. It is the wellspring of inspired followership.

Great leaders masterfully exercise all three types of voice.

Like a tuning fork, employees become followers when the projection of voice by leaders creates resonance. Followers experience directional resonance: “I buy-in to your vision.” They experience executional resonance: “I’m aligned with what you expect, I can accept the plan, and am ready to commit myself to my part of the plan.” But more than anything, followers are inspired and motivated by moral resonance: “I know you will do the right thing in all circumstances, that you care about me as a person, that you want me to grow, and that you have my back.”

Followership is not a costume, worn by your employees to retain their jobs. It’s a free will decision to commit the full measure of one’s passion, knowledge, and skills, and to submit to and trust in your authority. “Employee” is not the same as “follower.” Followership is an act of personal sacrifice, not yielded lightly.

A company can succeed for a time under leaders with strong directional and executional voice and weak moral voice. But such leaders ultimately forfeit followership, which, if you think about it, is everything.

Culture comprises the norms of behavior that guide company employees. It defines the acceptable range of freedom between total order (bureaucracy) and total chaos (anarchy). It reinforces acceptable authority patterns. It puts focus on business imperatives such as product quality and customer delight. It defines how human dignity is respected, and reveals the degree of attention the company places on human development. While leaders can and should guide and influence culture, it is ultimately created by what is heard and seen much more than by what said. Disproportionately, a culture is shaped by the observed values and behaviors of the CEO.

The leader-follower dynamic plays out in teams. Team. We should not use this word lightly. Teams are usually small: 2–8 people. Each team member possesses complementary skills in a relevant domain, in problem-solving and decision making, and in interpersonal effectiveness. A team exists for a purpose that is meaningful and shared. A specific, difficult-to-achieve objective is understood. Each member of the team buys into a common approach to its work, and everyone is ready to hold each other accountable. Everyone does real work and shares the load, including the leader. There is conflict — at times colossal — but inevitably the leader and followers nudge each other into collaboration. Without these attributes, a group is not a team.

Accountability is shared between leaders and followers, and amongst members of a team. The subordinate in the accountability relationship owns the obligation to report transparently on the status of an assigned responsibility. The superior owns the obligation to scrutinize, test, and challenge. This shared accountability plays out in all superior-subordinate relationships. Occasionally, it is also observed in team-based, peer-to-peer relationships. If so, this is a reliable indicator that the team has achieved elite levels of performance.

The words “leader,” “follower,” “healthy culture,” “team,” and “accountability” should not be used cavalierly. They are earned through the blood, sweat, and tears of real effort.

. . .

Joe’s back. He’s thought about it, and he’s come around to your point of view. On his brooding stroll to the corner Starbucks, he grudgingly put on the investor’s glasses. Peering through them, he realized you’re right. It’s the investor’s money. He needs to know. Even if we die. Which would suck. Vijaya nods as she types away on her computer; she’s been thinking the same thing. Joe returns to coding.

Your first job out of college, working at General Motors, didn’t prepare you for this. You had a job. It was very specific and straightforward. You were part of the dealer best practices team. You made a steady salary. You were the toenail on the elephant. The road kept coming to meet you; your job was to ride along, keep your assigned toe protected, and not get stuck on anything. But now you’re having coffee with a guy who is having serious second thoughts about whether it’s a good idea to write you a $500K check. It’s 9 AM, and it’s already been a long day.

Your potential angel investor, Anik Kapoor, has been peppering you for an hour about how you will solve the “have no customer” problem. Anik runs Kapoor Capital, an early stage VC firm, but he also makes angel investments on his own and he’s considering one now. So you go back over the size of the problem you solve. You remind him that at GM, you traveled the country, assessed dealer performance, and trained dealers in best practices. You noticed that dealers received all kinds of incoming leads, but on average one in five leads from car buyers was never responded to at all, and the ones that got a response had average response times of about 5 hours. And most of the responses were “give me your phone number and let’s talk” messages, no quote included. All of which left car buyers either long gone, or frustrated. Low customer satisfaction numbers proved it. You know with absolute conviction that if this problem can be solved, dealers will sell more cars. And by the way, $600 billion in new cars are sold in the US every year. Anik nods. He gets the problem. And the size of the market. But he needs to see a customer.

As you mull over your next response, your mind is reeling. You can’t be sure which dealership you can convince to buy your ½ price “beta phase” offer. Since you can’t know the yet-to-be-found dealer’s “DMS” (dealer management system), you don’t know if you can hack an integration to get into the dealer’s inventory, but you need this information to generate a quote. You also don’t know his CRM system, another point of integration risk. And even if you overcome these boulders, it is unclear whether or not you can get the dealer to enter and maintain his pricing rules accurately. These need to be entered into your not-very-user-friendly pricing rules interface. This interface is just one imperfect feature in your not-quite-minimum-viable-product.

So you tell Anik, “We’ll be up and running with a new customer in a week.” You mean it.

He looks into your eyes — for a solid minute. He’s expressionless. His brown eyes pierce with intensity. He says nothing. You don’t flinch.

Almost with resignation, he sighs. Anik tells you that if you have a customer live in one week, and the customer validates he’s excited and committed, he will invest $500K as a convertible note with a 20% discount to the A round and a $5M cap.

You flinch. The terms just got worse. But you stand up and shake hands. It’s all you’ve got.

. . .

Like basketball players competing against a talented squad, founders take any opening the defense gives them. High-level plans make some sense to set basic direction. However, as with the basketball coach’s whiteboard x’s and o’s during halftime, the moment the plan is completed, it’s out of date. You get back in the game, respond to the facts on the ground, pivot frequently, reprioritize constantly. You need a founding team of talented players that can act and react fast, and get to the net constantly seeking to “make something out of nothing.”

At this stage, your role as captain of the team is to lead by doing. It’s on you to sell the first handful of customers, score the financing, keep the team focused on the right product priorities, get the bills paid, help resolve team conflicts, and take out the garbage. Roughly in that order.

Before you shake hands with a potential co-founder, make sure you deal with two tough conversations: authority and equity. You are the CEO — your co-founders must accept that. You can fire them. You can reassign them. This they must understand. And because you’re the CEO, you command more of the equity. If you have three founders, the pre-money shares may be split 50/25/25, or perhaps even 40/30/30 — but should never be split 34/33/33. An equal split doesn’t make sense because this does not fairly reward you, the CEO, for the unique responsibility and burden of your role.

. . .

After a quick lunch, you get in your car, drive to Sunnyvale Ford, sneak by the receptionist, pop your head into the GM’s office, and catch the GM at his desk. Fortune is shining on you. Forty-five minutes later, you have a signed deal. Awesome. You call Vijaya, ask her to drive over right away to check out the CRM and DMS systems at Sunnyvale Ford and to begin to spec out the integration. You remind her we need to be technically live in 2 days. Then we must help the GM load in all pricing rules, which should take a day. That leaves four days of quote-sending (hopefully fault-free) before Anik calls the GM to test his excitement. No time to lose.

You pull into your apartment parking lot, hop out of the car, and take the steps two at a time. You remember the angel investors you’d planned to InMail by 7 AM this morning. Funding is never done until the money’s in the bank, so you can’t put all your chips on Anik. If other investors can be found, they should be found. You look at your iPhone. It’s 4 PM. Oh well, better late than never. By 7 PM 18 InMails have been sent. As you head to your room to catch a nap, you see on your iPhone that one has responded with interest.