You finally closed your $15M B round in May, almost a year after the A round. Imagination Capital led the investment; Kapoor Capital followed. Of all the people that made it possible, Victor and Serena are at the top of the list. The Fall trade show was most decisive in closing that round. The deals secured at the show, plus the ones that came soon after as a direct result of the show totaled over 100 stores. Once they were all launched (a massive challenge in its own right), company revenues popped up to a $5M run rate.

Even better, as more dealers switched to the SparkAction CRM, the buzz built throughout the auto dealer community. SDRs found it easier to get through on their calls, and the conversion to scheduled demo appointments improved. By Spring, the company’s revenue run rate was $7M, and trends pointed towards a $12M run rate by year-end. These numbers came at the perfect time. The exciting traction story propelled your B round, leading to a $50M pre-money valuation. With 18% of the company in founder’s shares, your paper net worth was now just under $12M. In less than four years, you went from drawings on a whiteboard to a company worth $65M post-money — and a transformative personal nest egg, at least on paper. Not bad.

With confidence in a predictable and repeatable revenue engine, you gave Victor and Serena permission to scale Sales and Marketing. In fact, your new investor — Mark Goldstein from Imagination Capital — had danced a one-note samba on your ear for the past four months: “Hit the gas! Hit the gas!”

This morning, you walked through the five-person Marketing department and the fifty-person Sales department. Despite adding nine thousand square feet to your office space; you were using it up fast. You reflected on the fact that across the country, in Boston, New York, Chicago, Dallas, and Los Angeles, five Regional Sales Directors were presently securing meetings with principals at the country’s largest dealer groups. Here at headquarters, the sales department was abuzz with chatter. Yes, the engine hummed.

To his credit, at the Fall trade show, Victor dealt head-on with his inappropriate treatment of Serena in the Bobby Petrak meeting. He knew he owed Serena an apology, and he gave her one — right away. Serena graciously accepted it. They went out to dinner that night and had a long conversation. So began a new chapter in their business relationship.

Now, nine months later, it’s a whole different story. Victor and Serena are power partners. They developed an integrated attack plan for gaining new customers, and it’s working. The Sales Operations and Marketing Operations directors are a well-oiled workflow team. As Marketing generates leads, Sales now receives and follows up on them with efficiency and effectiveness (from lead, to call, to a scheduled appointment, to a held appointment, to a Closed Won conversion).

To drive brand awareness, Serena built a comprehensive, multi-touch engagement strategy — integrating thought leadership, active participation on auto dealer social blogs, strong SEO efforts, selective digital demand generation spending, “lunch and learn” meetings in the big markets, and a significant trade show presence at the three shows a year that matter most. She took an account-based approach, building a database of all the single-store dealerships and dealer groups in the US and Canada with the names and contact information for all decision makers and influencers. Marketing uses this data for email campaigns and Sales for telemarketing. The messaging schema that drives the campaigns and telemarketing talking points is spot on, customized to different segments and personas (for instance, dealer groups vs. single store, and dealer principals vs. store GMs). It all came at a price — non-labor marketing spend now exceeds $2M a year — but it’s worth it.

Your new head of Finance, Jack Waltz, joins you in today’s Q3 board meeting. He presents the Financial Performance update. Imagination Capital led the B round with a $9M investment. Anik Kapoor’s firm, Kapoor Capital, came in with $6M more, and Fess Fieldstone invested another $1M. Upon close of the B round, the investors agreed that common shareholders would hold two board seats. So the SparkLight Board of Directors now boasts as its members: Goldstein, Kapoor, Fieldstone, plus you and Joe.

The Fall trade show is again around the corner; you are mobilizing for another breakout show. Right after that, it’s renewal time: in the next two months, over eighty contracts will come up for annual renewal. Victor is preparing for that as well.

As your board meeting wraps up successfully, you remind everybody of the next meeting — December 10. At this next meeting, you will approve the Financial Plan for the coming year.

You thought ahead. As you shake hands with your board members and walk out, you look forward to the exec group retreat you set up for two weeks from today. At this two-day retreat, you will nail down the key strategic initiatives for the next six months, and secure every executive’s commitment to the Plan for the coming year.

. . .

It helps to start with first principles.

Responsibility can only be assigned by someone with authority to assign it. In the governance of a company, authority relates to stock ownership. Owners select the board which has control. All things being equal, the owner of the highest number of outstanding shares wins. But things are not always equal. VCs and other investors often receive preferred shares carrying supermajority voting rights or rights to a disproportionate number of board seats.

The board is the ultimate decision-making body — it has decision control. The board delegates possession of authority to the CEO, within pre-defined boundaries. The CEO delegates authority to executives, who delegate authority to their subordinates.

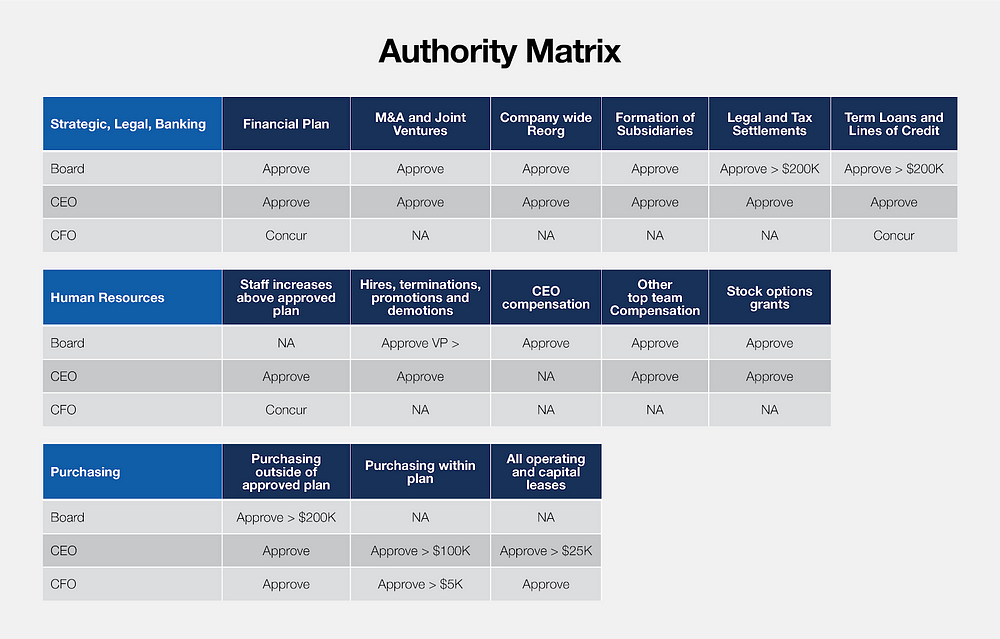

Ownership, control, and possession — these are the building blocks of authority. Here is a typical authority matrix for an early stage startup:

Let’s assume you have full authority as CEO to design the organization of your choosing. In your organization design, you must allocate responsibility and authority to specific roles. Associated with each box on the org chart, you first define the role itself regarding its responsibility. Responsibility includes:

- Span of control

- Span of influence

- Activity expectations

- Output expectations

Once you clarify responsibility, you then determine the amount and type of power — called “authority” — you delegate into the role.

Span of control decisions are crucial. The higher up the hierarchy you go, the wider the assigned responsibility and more expansive the delegated authority is likely to be. While broad responsibility and significant delegated authority are the norms at the executive level, it’s still critical to be crystal clear on specifics. Faced with any vagueness, an executive incumbent will interpret span of control expansively, while those around her will likely interpret it narrowly. Political infighting is the inevitable result.

As CEO, it’s also essential for you to help each executive define her span of influence. If the span of influence is not clarified, executives may miss opportunities to develop strong cross-functional partnerships, and the risk of cross-functional conflict rises. When executives nurture their most critical peer relationships through healthy mutual influence, silos break down and more gets done.

At the top, activity and outcome expectations derive from strategy: direction-setting, financial planning, and strategic and financial goal achievement. As you move down the organizational hierarchy, activity and outcome expectations are increasingly tactical. At every level, clarity is critical as to each position’s activity and outcome expectations.

Authority follows responsibility. Every time you define the responsibility for a role, you must determine what level of authority to delegate to it. From board to CEO, CEO to executive, executive to mid-manager, and mid-manager to individual contributor, these delegation decisions contribute to leadership leverage. A central principle drives the effective delegation of responsibility and authority:

Always push responsibility and authority to the lowest viable level, given the circumstances.

Two factors drive this decision. First, you must understand the current task-relevant maturity of the responsibility recipient. Is the assigned responsibility too much of a “stretch,” causing the delegated authority to be excessively broad?

Your decision on the “stretch” question depends on context. What’s the risk of failure? If the cost of failure is modest, there is room to stretch more. Why? Because in the act of attempting to fulfill an assigned responsibility and execute delegated authority, an employee’s task-relevant maturity grows. People learn by doing; the more you give people “stretch” responsibilities, the more they grow. This is how young pilots learn how to land fighter jets on aircraft carriers.

But sometimes the cost of failure can be very high. Ben Horowitz talks about “peacetime” leadership vs. “wartime” leadership. When it’s wartime — when the future of the company hangs in the balance, or major strategic initiatives (such as a planned exit or IPO) are underway — a more “command and control” leadership approach is merited. But (all things being equal) if you’re leading the company in “peacetime,” empowerment is usually best.

The point is this. An employee’s effectiveness in fulfilling an assigned responsibility and exercising delegated authority is not binary. There’s an effectiveness continuum. And your employee’s effectiveness is not static — it’s dynamic. The act of trying to do something helps a person become better at doing it.

From top to bottom, your decisions as to the assignment of responsibility and delegation of authority are laden with consequence. They impact not just the immediate performance of your company, but also its future performance. Delegation doesn’t just drive performance; it builds performance capacity — through “teachable moments” that elevate the collective competency. This, in turn, frees top leadership to gaze deeper into the future, think bigger, and act with more ambition.

That’s leadership leverage.

. . .

Two weeks after the board meeting, you convene the two-day exec team retreat at the Ocean View Inn in Montara, just a thirty-minute drive down the coast from San Francisco. It’s a spectacular location, perched on a cliff overlooking the Pacific.

Bill is a great VP Customer Success. He works hard to move customers to “happy” and has an extraordinary capacity to defang an angry dealer. Bill now leads a team of ten customer success managers. He created a technical infrastructure that delivers alerts to the CSMs when dealers fall below what he calls a “happiness threshold.” Fifteen different thresholds are in place. For instance, a fall-off in platform usage, or slow lead follow-up, triggers an alert to a CSM to make a phone call and check in.

It’s a golden morning, and outside the big bay window row after row of waves crashes against the rocks, creating an erratic, rumbling percussion up in the conference room. At 8 AM, Bill is the first to join you. After Bill, your new CEO coach, Rohit, arrives to facilitate the retreat. Next comes Sally Jenkins. Sally is your VP Human Resources, hired three months ago. Moments later, Joe, Vijaya, Serena, and Victor walk in together. Finally, Jack Waltz’s lanky 6’2” frame comes through the door, and everyone settles in.

It is not your first exec retreat — but it’s the first with a complete executive group. The entire cast is now in place: VP Engineering, VP Product, VP Marketing, VP Sales, VP Customer Success, VP Finance, and VP HR. You assembled all the building blocks necessary to scale. Suddenly it hits you: what an epic journey it’s been. We’ve come so far. There’s so much farther to go.

Your opening presentation starts with mission and vision:

Mission: To deliver transparent, data-driven, omnichannel communications between car owners and car dealers that simplifies engagement, speeds conviction, and enhances delight.

Vision: To become the leading omnichannel auto dealer CRM in North America and Europe through superior transparency, simplicity, and comprehensiveness.

You then review progress regarding product and financial results. Next, you identify the board’s expectations for the new year — $20M in revenue — and propose four strategic initiatives that will get you there. These address building out the product, scaling the revenue engine, increasing customer delight, and creating a healthy culture.

You then describe the agenda for today and tomorrow. Today is devoted to a “deep dive” into the four strategic initiatives (including the projects and milestones required to achieve them). Tomorrow’s focus is to build out the fundamental planning assumptions for the financial plan that you will bring to the board.

After you sit down, Ro hops up. She walks over to two flip chart stands and asks Bill to stand by one, and Vijaya to stand by the other. One flipchart says “Hopes.” The other says “Fears.”

“OK we will go around the table now, and I will ask each of you to raise one hope and one fear. Bill and Vijaya will capture your comments on the flip charts. We’ll keep going around until everyone exhausts all their hopes and fears. So think about SparkLight Digital’s current position, both internally and externally. Consider the financial objectives the board issued and the four strategic initiatives outlined today. Think about what this will require of you, your peers, and the people you lead. What are your hopes? What are your fears? Sally, let’s start with you.”

Sally hopes that as the company scales, SparkLight Digital maintains its unique culture. She fears that silos will grow and it will be harder and harder to keep a startup mentality and interdependent spirit. She’s also concerned about preserving the culture in remote offices. Other executives pile on, raising concerns about the aggressiveness of the growth objectives, how product roadmap prioritization decisions will be made, whether we’re burning cash too fast, workflow breakdowns that are getting in the way, and so forth.

When Ro turns to Joe, he sighs. “I hope that we can carve out time to overhaul our technical stack and to build on the scalability, stability, security, and speed required for the growth levels you guys are talking about. My fear is that we’ve been on such a mad scramble to survive and push product to market, we’ve never taken enough time to architect everything perfectly. There is technical debt, and we’re not spending enough resources to clean it up. Everyone keeps wanting more new features — but I’m concerned about the stability of what we already have.”

Ro organizes the hopes and fears feedback into five key themes. She encourages everyone to consider these themes as she turns to the four strategic imperatives. The first strategic imperative takes one and half hours to complete. Same for the second. Lunch comes at 12:30 PM and, by 1 PM Ro has everyone at work on the third strategic imperative. In each case, she leads the team through a set of questions: what are the critical requirements for achieving this imperative? What are the obstacles? What key projects must be mobilized? What milestones and outcomes? Who will lead and who will be involved?

It’s now 3 PM, and Ro shifts the conversation to the final strategic imperative. Optimism grows in your heart; the session is going well. As you think about tomorrow when you will translate these four initiatives into your financial plan for the coming year, you sense it’s all coming together just as you intended. The financial plan should roll up to the numbers the board wants. The exec group will be aligned. The board will be satisfied.

You can’t wait for tonight. Dinner at La Costanera, the sublime Peruvian restaurant you and Joe went to after your all-day 1:1 retreat a lifetime ago. You can almost taste your first sip of Pisco Sour, La Costanera’s famous cocktail.

Suddenly Joe bolts up. He holds his iPad like a scandal. He sits right back down, pulls out his laptop. Eyes wide, he stares at his screen and types. As he logs into the platform admin console, he goes stone cold.

“Shit,” he says. “The entire system is down. It looks like we’ve been hacked.”

Vijaya and Bill run over, looking over his shoulder. “Oh crap!” Bill says. “Check the log files,” Vijaya says. Joe’s iPhone buzzes to life — Farook and Foster on the line.

It’s bad. Joe, Farook, Foster, and Vijaya search through the log files to find the source of the hack, to no avail. As the scale of the problem comes into focus, Bill starts emergency procedures. Inside Salesforce, he sends an email to all system users — over 700 people in dealerships all across the US — alerting them to the system outage. He indicates that the technical team is fully mobilized and working to understand the problem — but we don’t yet have a recovery estimate.

Within minutes, Bill’s Customer Success team in the San Francisco office is texting him, saying the phones have exploded with calls. He hastily arranges a conference call to give his team an update and discuss the emergency protocol.

For an auto dealership, the CRM is its central nervous system. When the CRM goes down, the dealership can’t receive leads, call prospective customers, view appointments, or track performance. For an auto dealer, it’s a crisis if the CRM goes down more than three hours.

For the 185 stores live on SparkAction CRM — and their 735 salespeople, internet directors, general managers, and dealer group principals — it was a crisis indeed. Email update followed dutiful update, but Bill’s customer status updates could only say what dealers already knew. The system was down.

For three days.

. . .

Please visit us at CEOQuest.com to see how we are helping tech CEOs of growth-stage companies achieve eight-figure exit value ($10m+).