Your board meeting is going well — in fact, the excitement is palpable. Everyone leans in. The three VC partners are to your left (Mark Goldstein from Imagination Capital, Sal Infante from Smash Capital, and Anik Kapoor from Kapoor Capital). Fess Fieldstone and Joe are at the end, across from your spot at the head of the table. Everyone fixates on your slides as you stand at the front of the room and go through them.

Fess can barely contain himself. Three times already, as you made a key point, he interjected with verbal punctuation (“Amen,” “Yes, yes, yes,” and “That’s what I’m talking about.”).

Slide by slide, you unfold the data. It’s abundantly clear that SparkAction CRM 3.0 is an out-of-the-park home run. You just crossed 1000 dealers on the platform, with a backlog of closed won deals waiting to launch. Annual revenue run rate is $18M and climbing fast. Logo churn dropped to 12% a year. And the dealers who started with the sales side CRM are now upgrading to the service side at twice the price. The revenue gains from these existing customer expansions surpass the lost revenue from customers who cancel — which means negative revenue churn. Competitor pricing actions and bad-mouthing provide proof positive that SparkLight Digital is a serious threat to incumbents.

Finally, Fess slams his fist on the table and jumps to his feet. “Dammit, we’ve got a racehorse by the neck, and we’re keeping it in a corral. This thing can fly. The guys at every one of my stores tell me this CRM has got the sales guys and the service guys working together like never before. Sales and profits are up at all my stores. SparkAction CRM 3.0 is the reason. Now we gotta make damn sure the other CRMs don’t have time to catch up. Get the horse out of the barn, put it on a fast track, and give it a kick,” he says.

There is unanimous agreement. It’s time to hit the gas. For that, you will need another funding event. You and the board agree you will raise a $30M C round, targeting a close in two months. The money will give you the dry powder to aggressively scale up marketing, sales, and customer success — and invest more in product and engineering. You set the target at $70M pre-money valuation. Given your traction story, and the fact you have 15,000 more dealers available to sell to in the US alone, you’re confident you can get it done.

. . .

Hire slow, fire fast.

For tech startup CEOs, this is a critical rule of thumb. In a growing company, your future depends not so much on ideas, traction, or capital, but on talent. With the right talent, the ideas, traction, and capital follow. So every hiring or promotion decision is consequential. Hire by hire, promotion by promotion, you build the collective competency and capacity of your company. Hire and promote well, and the future opens like an oyster. Hire and promote poorly, and it sinks like a stone.

Recruiting and Hiring

The choice to hire someone is a wager of time and money. As in a poker game, it starts with an ante. The ante is your deep understanding of why you need the job in the first place. Sound organization design should lead you to the conclusion that the job, its requirements, and its timing are appropriate.

You then consider your betting options. You recruit for the skills and capabilities you seek, moving candidates from top of funnel, to mid, to bottom. You conduct a thorough assessment of finalists, including conversations with references. Finally, you place your bet. You bet that you understand enough about the prospective hire’s domain expertise in relation to job requirements. You bet that this person has the commitment level to do the job conscientiously and consistently. And you bet that this person is culturally aligned.

The unfortunate reality is that most hiring managers bet wrong. Leadership IQ’s Global Talent Management Survey, published in 2013, showed that an astonishing 46% of all new hires fail within 18 months. Further, only 19% of new hires are an unequivocal success.¹

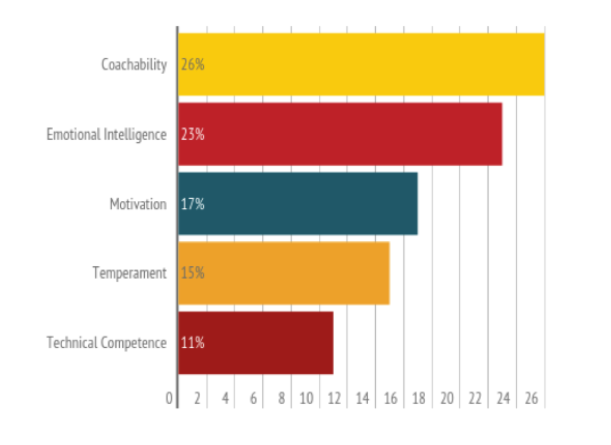

The three-year study surveyed 5,247 hiring managers from 312 public, private, business, and healthcare organizations. Collectively these managers hired more than 20,000 employees during the study period. Interestingly, only 11% of failed hires were due to a lack of technical skill. Attitudinal problems drove the majority of failures. The following chart depicts the primary failure areas:

For a tech company, failure at this rate exacts a considerable cost. Productivity declines as poor performers disrupt workflows. Culture damage occurs as good performers become tainted and demoralized by the duds around them. A divergence between expected results and actual results creates lost time. And management attention on the business declines as the “Performance Improvement Process” (PIP) black hole expands. Executives spend precious time documenting performance shortfalls and giving warnings to comply with legal requirements for employee termination.

Surely there is a better way.

In 1998, when Amazon had about 6000 employees (today there are 541,000), CEO Jeff Bezos said, “Setting the bar high in our approach to hiring has been, and will continue to be, the single most important element of our success.”² To achieve this objective, Amazon created a new role in the business: the “bar raiser.” The company assigns this role to full-time employees who distinguish themselves as model Amazon employees. Bar raisers redirect half of their time (20 hours or more per week) to interviewing candidates. One condition of employment at Amazon is that new hires must raise the average productivity of the group they enter. Bar raisers bring an independent perspective to that evaluation. Each prospective employee has five interviews of 2–3 hours each. Since the bar raiser is not the hiring manager, he is not influenced by short-term pressure to fill a vacant position. Armed with an irrevocable veto right, he can simply focus on quality. Bezos once said, “I’d rather interview 50 people and not hire anyone than hire one wrong person.”

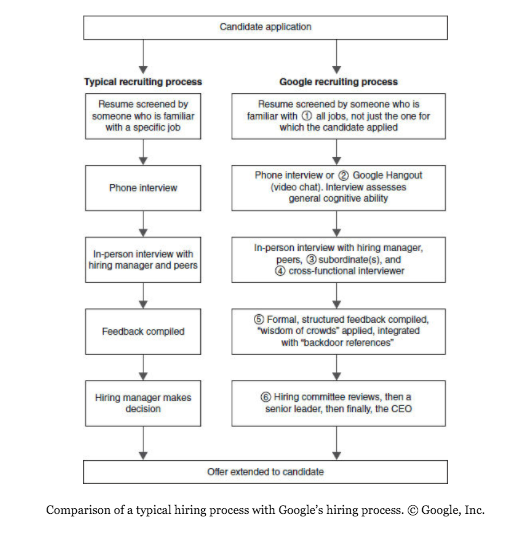

Google is another company with a highly selective recruiting and hiring process.³ Google uses data analytics to optimize every step. The company rigorously tests the predictive value of every recruiting and interviewing technique. For instance, at the top of the funnel, they determined that role-related tests and general cognitive ability tests are the best initial filters. A team of people, following structured interview questions, interviews each prospect who gets through the first stage filters. The average of all interviewer scores (unweighted by level) gives the highest accuracy rate, predicting success 86% of the time. Google’s 86% success rate compares favorably to the previously noted 46% new hire failure rate for the average company.

Google spends twice the time in new hire selection than other companies do. They consider many candidates but choose very few. General cognitive ability, emergent leadership potential, and “Googliness” (capacity to have fun, pursue curiosity, and work conscientiously) are the top three criteria. Role-related knowledge is the final, least important factor.

Here is Google’s recruiting and hiring process. The numbers in the graphic indicate points in the process that are unique to Google:

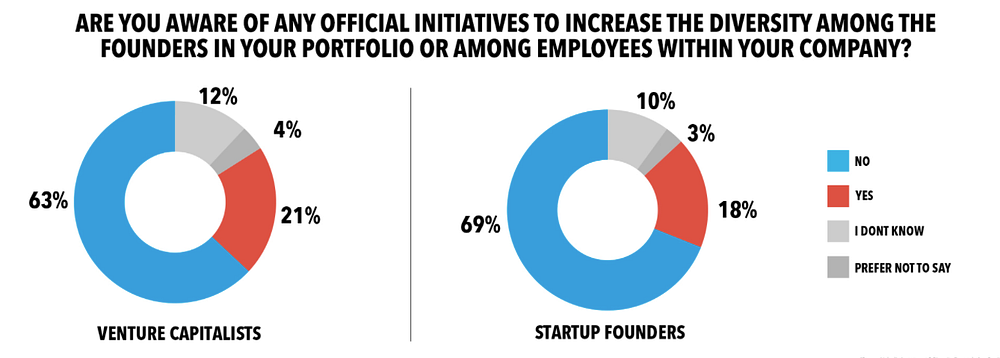

More recently, both Amazon and Google place a high value on diversity and inclusion. The tech sector lags in this area. For example, LinkedIn’s 2016 tech diversity survey found that less than 1 in 5 founders and investors surveyed said their companies had official diversity initiatives in place, as the following graphic illustrates:⁴

Too many tech companies consider gender parity and racial, ethnic, age-based, and orientation diversity a secondary or tertiary concern. This is wrong. In a Harvard Business Review article titled, “Why Diverse Teams are Smarter,” authors David Rock and Heidi Grant cite multiple research studies showing superior performance from diverse teams.⁵ The research showed that diverse teams tend to be more data-driven than homogenous teams. This characteristic, among others, drives superior results.

One tech company that pursues diversity with vigor is Yelp. After publishing initial research showing its low levels of diversity, the company set about to change the situation. Yelp now sets specific targets for diversity. In three years, the company increased the percentage of women engineers from 10% to 18%. At the same time, the percentage of Hispanic employees increased from 7% to 10%, and black employees from 4% to 6%.⁶

Diversity and inclusion are critical not only for social and societal reasons but also because they make companies stronger. Yes, a diverse workforce may present extra challenges for leaders to build common ground given an increased variety of life experiences and perspectives. But ultimately, efforts to build diverse and inclusive teams yield higher levels of performance and more holistic decision-making.

The practices at Amazon, Google, and Yelp are instructive. They remind us that a company’s collective competency builds one hire at a time. Google’s first filter is intelligence. Amazon’s first filter is productivity. A primary filter at Yelp is diversity. What are your filters? The failure rate data noted above implies that emotional intelligence should be another primary filter. Step back and think about what matters most in your employees, and apply these filters to every hire.

All of these requirements may increase the length of the hiring process. So be it. If you have to repeat a pattern over and over, it’s better if it’s “hire slow” than “fire fast.”

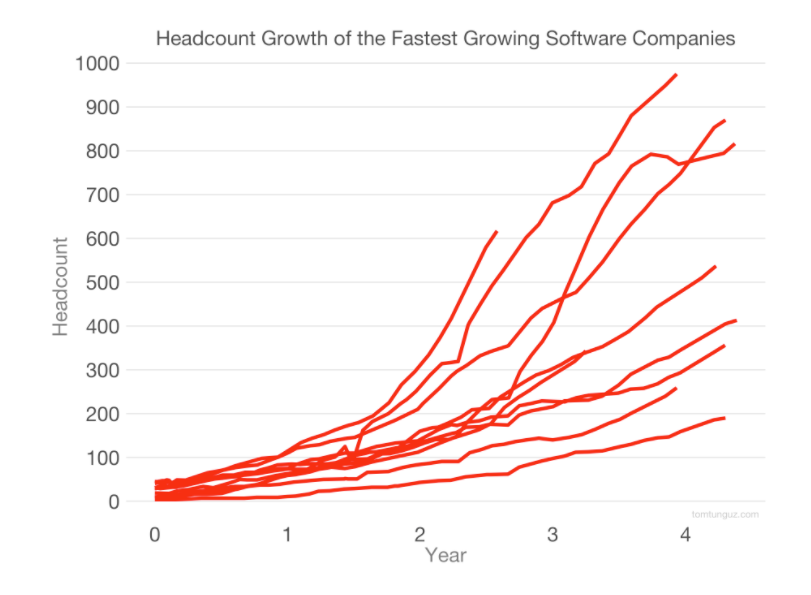

For a fast-scaling company, a “hire slow” mentality introduces a creative tension. You must figure out how to hire slow while hiring many. Tomasz Tunguz from Redpoint Ventures researched the fastest-growing software companies, assessing their headcount growth starting from year zero at 50 employees or less. It looks like this:⁷

The companies represented here all have strong product/market fit in a large market. They made the strategic decision to scale as rapidly as possible to create market dominance. To get there, they sufficiently capitalize their businesses to support rapid headcount scaling. The constraint on headcount growth in these companies is recruiting capacity, not cost.

How does such a rapid headcount growth rate square with the “hire slow” approach? Indeed, a fast-growing company could achieve its headcount growth objectives by loosening standards. But as both Amazon and Google demonstrate, it’s possible to keep standards high while scaling at a rapid pace. Achieving both requires a hefty investment in money and the time of existing employees.

Recruiting and hiring require substantial effort, especially when you adopt the “hire slow” approach. The process begins by designing a job that is interesting and fulfilling for the target candidate. Then, at the top of the funnel, you must publicize the job posting so that as many qualified candidates as possible see and consider it. In mid-funnel you need a tightly defined, thorough, and fair filtering process. And at the bottom of the funnel, you require competitive compensation and attractive work benefits.

Achieving rapid headcount growth combined with a “hire slow” approach requires significant resources. But if you keep standards high and match your recruiting budget and employee time allocation to the demand for new hires, you’ll scale while elevating collective competency.

Hiring Engineers

For a tech company, no hires are more critical than engineers. The quality and productivity of your engineering group gates the scalability of your product. You must anchor the engineering group with elite senior engineers capable of architecting and building scalable, flexible, secure infrastructure and applications. If you intend to develop a new search engine or offer a complex data or infrastructure platform, you may require many of these senior engineers. Such hires take considerable effort, time, and money. The most prized tech recruiters in the world leverage sophisticated data-driven tools and methods to find and pursue such candidates.

But be careful. Senior engineers are in rabid demand everywhere. They cost a lot of money, and because of the demand/supply imbalance, they can often feel entitled. Every senior engineer on your team is just one bad day and one compelling offer away from leaving you.

For most companies, the bulk of the team doesn’t need to be at this elite level. As Avi Flombaum, Dean of the Flatiron School, says, “The bottom line is that for most products, seeking out rock star engineers is like trying to hire Picasso to paint your apartment.”⁸

Promoting

Sometimes it’s obvious. Your company grows to the point where you need a manager, a director, or a VP. Someone on the inside distinguishes herself, and you are confident she is promotion-ready. Alternatively, it may be equally evident that no one in your organization qualifies for the position you require. Both of these situations are easy in the sense that the next right step is clear.

Sometimes it’s more difficult. A potential internal candidate has some but not all of the qualities you seek for an open management position. Do you go with the inside candidate or go outside?

The decision to promote or hire is consequential; both involve risk. As mentioned earlier, new hires fail almost half the time at the average company. Even at companies with top-tier recruiting practices, new hires fail 20% of the time. If you hire from the outside, your new employee enters the company on day one as a foreign object. It takes time to assimilate an external hire into the company culture. The new employee brings new perspectives, but there is risk of a cultural mismatch. On the other hand, promoted employees are likely to be more culturally assimilated, though as a result they may have blind spots.

If the promotion candidate exhibits a gap between desired and current competency, ask yourself if you have resources available to coach and develop. If you’re in a wartime situation with the company’s future on the line, you may feel you need to bring in a “proven hand” with an established track record. Even then, beware of the superhero syndrome, where you overweight an unknown external candidate’s seemingly impressive background while underweighting the direct experience and proven results of a promising internal candidate. At all other times, when in doubt the promotion path wins. The promoted employee is typically highly motivated to grow into the job. And for all other employees, they will realize they work in a company that provides advancement opportunity.

Your hiring decisions send a cultural signal that impacts the motivation and performance of everyone in the company. Optics matter. This is why you cannot reduce the external vs. internal decision to a prediction of work output for the job in question alone. Over time, a series of decisions to hire from outside instead of promoting from within may cause your employees to conclude that you don’t value upward mobility. And they will act accordingly.

. . .

Since the beginning of SparkLight Digital, you raised over $65M in capital, including the $30M round you recently closed from Bain Capital. Flush with cash, you now have all the resources you need to scale. The only constraints are your capacities to promote, hire, and onboard employees successfully. Despite the focus on all three, you are not at all happy. In fact, you feel like your feet are stuck in mud, or quicksand.

Your conversation with Sally Jenkins, the VP of Human Resources, drags on for over an hour. It’s not going well. You review the facts. Employee attrition averages one per month (12% a year). You approved twenty-five new positions since funding closed two months ago. Since then, just four new employees joined. And two resigned — meaning a net increase of two. Unacceptable.

To make matters worse, the two new hires resulted in short-term productivity losses since the complex hiring process required nearly 80 hours of interviewing for a yield of two new employees.

Finally, you recently promoted six people — two in Sales, one in Marketing, and three in Customer Success. For four of the six promoted employees, the new job is a big stretch. You planned to backfill the open positions quickly and set aside extra time for you and other senior execs to coach and develop the promoted employees. But now, due to the anemic pace of hiring, all six remain in their old jobs as they await relief from the backfill hires.

Your difficult conversation becomes more difficult as Sally doubles down.

“I agree we need to increase the pace of hiring,” she says. “But I’ll be damned if I agree to increase the speed of our hiring process. We have a multi-step, multi-stakeholder hiring process for a reason. Quality is everything. I don’t want to be dealing with a rash of PIPs and terminations in six months because we talked ourselves into hiring poorly.”

“But do the math, Sally,” you say. “You are averaging 39 hours of interview time per hire. If we want these open positions filled within three months, then you’d be asking us to invest over 1000 hours of existing employee time in interviews. That would kill productivity. That’s the equivalent of two people working full time, just interviewing, for the next three months.”

Sally raises her eyebrows. “I know exactly what it means,” she says. “Put another way, for the next three months ten people need to set aside one day a week to conduct interviews. In fact, I am making that exact proposal. Here is the list of the ten people we need dedicated to this day-a-week interview process.”

She hands you a sheet of paper. “As you can see, it includes five of our exec team members: Victor, Serena, Bill, Joe, and Vijaya. And five more from their teams — one director, one manager, and three individual contributors.”

She continues as you glumly scan the sheet. “I already lined up enough recruiters. They are starting to drive the necessary volume of qualified candidates. But you are going to need to tell these ten people to free themselves a day a week for interviews. If you don’t, our capacity to hire will crumble. They will need to figure out how to manage their day-to-day work in 20% less time. Specifically, they are going to lose their Tuesdays. Unless you overrule me on this, their Tuesdays are about to be filled up with interviews.”

You walk away stymied. Twenty-three positions remain open. Six promoted people can’t get into their new jobs. A wider hiring pipeline is essential to solving both of these issues. To do that, the very execs who should be coaching the promoted and running their functions harder and faster will be sucked into an interviewing black hole for at least three months.

You grudgingly acknowledge that Sally’s right — it’s the only way to scale with quality.

Ugh.

. . .

Next up “Chapter 17: 150 Desks — On Managing Workflow Groups”

To see all published chapters of People Design, please click here.

Please visit us at CEOQuest.com to see how we are helping tech founders and CEOs of startups and growth-stage companies achieve $10m+ exit valuation.

. . .

Notes:

- Mark Murphy, “Why New Hires Fail (Emotional Intelligence vs. Skills),”leadershipiq.com, June 22, 2015, https://www.leadershipiq.com/blogs/leadershipiq/35354241-why-new-hires-fail-emotional-intelligence-vs-skills.

- Alan Deutschman, “Inside the Mind of Jeff Bezos,” fastcompany.com, August 1, 2004, https://www.fastcompany.com/50661/inside-mind-jeff-bezos.

- Laszlo Block, Work Rules!: Insights from Inside Google That Will Transform How You Live and Lead, (London: John Murray Publishers Ltd., April 22, 2015).

- Caroline Fairchild, “Investors and Startup Founders Think Tech’s Diversity Problem will Solve Itself,” linkedin.com, November 2, 2016, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/startup-founders-investors-think-techs-diversity-solve-fairchild/.

- David Rock and Heidi Grant , “Why Diverse Teams are Smarter,” Harvard Business Review, November 4, 2016, https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter.

- Rachel Williams, Gauri Subramani, Michael Luca, and Geoff Donaker, “Lessons from Yelp’s Empirical Approach to Diversity,” Harvard Business Review, September 20, 2017, https://hbr.org/2017/09/lessons-from-yelps-empirical-approach-to-diversity.

- Tomasz Tunguz, “How Quickly Does Headcount Scale in the Fastest Growing Software Businesses?” tomasztunguz.com, November 29, 2017, http://tomtunguz.com/headcount-growth/.

- Avi Flombaum, “Startups: Stop Trying to Hire Ninja-Rockstar Engineers,” onstartups.com, August 6, 2012, http://onstartups.com/tabid/3339/bid/87890/Startups-Stop-Trying-To-Hire-Ninja-Rockstar-Engineers.aspx.