SparkAction CRM crossed 4,000 dealer stores in June, punctuated by the re-signing of the 130-store McBride Auto Group. One year on DealerGasket’s CRM system and McBride store general managers throughout the country were frustrated by its limitations, especially the cumbersome price quote feature. All around them, competitive stores on SparkAction CRM sent out accurate price quotes every day, without the manual entry of monthly incentives required by DealerGasket’s CRM. Soon, GMs at McBride stores mobilized an internal campaign of complaints and demands. Finally, Jack Acton, SVP Operations at McBride, canceled DealerGasket and authorized the switch to SparkLight Digital’s SparkAction CRM. All 130 dealerships launched within eight weeks of signing.

By crossing this milestone, SparkLight Digital now boasted a market share of 25% in the automotive CRM market. DealerGasket was second at 14%, with the remainder of the market made up of many smaller players. SparkLight Digital’s annual revenue run rate exceeded $130M. Reflecting on your success was exciting. Only seven years ago, your ideas for this company consisted of whiteboard drawings. Now you were CEO of a 280-person company with offices from Bengaluru, India to Kansas City, to San Francisco — plus sales offices in New York, Atlanta, Dallas, Chicago, LA, and Toronto. In seven years, you raised over $115M in venture funding — the most recent a $50M E round anchored by Bain Capital, your D round investor.

Despite your pride and excitement, you knew that there was no time to rest. With the dominant share position in the automotive CRM market now in hand, the limits to company growth began to loom. If SparkLight Digital were to remain just an automotive CRM company, growth would eventually cap out.

You and Rohit, your CEO coach, prepared extensively for an exec group strategy retreat. Together, you framed the financial dimensions of the challenge. The board, with its recent addition of Aleksandar Savic from Bain Capital, gave you a goal to take the company public within three years. To maximize valuation at the time of the IPO, you would need to continue to grow at a minimum pace of 30% a year. In other words, in three years the revenue run rate had to be over $280M. If SparkLight Digital remained an automotive CRM company only, such growth would be virtually impossible. The entire auto CRM market (the total addressable market, or “TAM”) comprised under $500M. And even if somehow you could get there in three years, there would be no room left for future growth.

That left two options in the automotive vertical. The first was to extend further into the automotive digital space. In the automotive digital market, two product categories of significance remained available for expansion: dealer website platforms ($700M TAM), and the financial systems called dealer management systems or “DMS” ($2B TAM). Another option would be to extend beyond auto, into other market verticals.

The latter option was worth considering. SparkAction CRM’s distinguishing capability was its capacity to provide consumers information about products of interest — including the price — before they walked through the doors of a store. This arms-length data-gathering step built trust. Consumers got comfortable with pricing and selection first via online interactions. By the time they entered the store, price resistance was invariably lower and propensity to buy higher.

Over the years at different gatherings, you sometimes met people running various types of retail operations. These purveyors of furniture, heavy machinery, boats, motorcycles, and RVs uniformly found SparkAction CRM’s capabilities interesting. You heard more than once that such capabilities could be as relevant for selling a sofa (or a tractor, lawn mower, or RV) as they were for selling a car.

These possibilities and questions became research projects for different executives to test hypotheses before the strategy results. With two months of preparation time, you expected solid work. As you assembled your executive group for the strategy retreat at a funky hotel in Half Moon Bay on a warm, sunny mid-September day, you looked forward to a vigorous debate. You sensed that the company’s very future hinged on its outcome.

On the first day, the retreat convened in the boardroom. Around you at the table sat Joe (co-founder and VP Engineering), Vijaya (VP Product), Bill (VP Customer Success), Victor (VP Sales), Serena (VP Marketing), Tina (VP HR), Jack (VP Finance), and Rohit, your CEO coach. As you looked around the room, everyone abuzz with chit-chat, you took a moment to reflect. Joe and Vijaya were with you from the beginning. They grew from individual contributors to leaders running sizable staffs of engineers and product managers. Bill struggled through tragedy to become a highly talented and valued executive, now running a customer success group of fifty people. Victor and Serena were completely different personalities. At first, it seemed they would inevitably crash and burn. But they eventually figured out how to work with each other, and now they were a real power partnership. As to Jack Waltz, he runs a stable ship in Finance — though in a year or so you will appoint the person who takes the company public to act as CFO above him. Jack knows this. And Tina, though new, is proving to be a reliable HR partner, providing unvarnished feedback about the health of the culture and the assessment of talent. With a swell of wonder, you marveled that all rose to the moment and seemed ready for the epic journey ahead.

You began your opening presentation by laying out a bold challenge: “Together, we will take SparkLight Digital public within three years.” You underscored that this would require sustaining a high growth rate. You posed three questions:

1. To become a $280M revenue company in three years, what revenue contribution must come from SparkAction CRM itself, from new automotive digital products, and from products serving verticals outside of auto?

2. If new products, what products? If new verticals, what verticals?

3. Given the desired revenue mix, what will it take to get there?

Over the course of two days, each executive presented research and provided insights and opinions. Presentations, debates, brain walks, and Post-It note exercises commingled in a symphony of ideation and discernment. When discussions deteriorated into rat holes or people got stuck holding onto positions, Rohit, your CEO coach, artfully guided the group back on track. By the end, a consensus emerged. You would propose a plan to the board to expand immediately into the boat, RV, and motorcycle markets. The product adjustments required to meet the needs of these markets were thought to be small, so it felt like the right place to start. The heavy machinery and furniture markets would soon follow.

Meanwhile, you would bring on a banker to help you identify and cultivate acquisition targets in the dealer website platform space. Some interesting companies served that market. There would be substantial synergy between the lead generation capabilities of a well-designed, consumer-centric dealer website, and the lead follow-up capabilities of SparkAction CRM. You theorized that such synergies would give you a significant sales advantage.

The one-two punch of vertical expansion plus acquisition-driven expansion would be SparkLight Digital’s ticket for growth heading into an IPO.

As the retreat wrapped up and you all headed to La Costanera for dinner, you felt confident that you had an ambitious plan to support taking the company public within three years to bring to the board.

Flush with excitement and anxiety, you plunged headlong into a future of your creation.

. . .

As your company scales, one critical architectural decision is how to balance horizontal and vertical structures. The choice you make in this regard has significant consequences for your company’s market focus, efficiency, management control, and employee empowerment.

You will recall from Chapter 11 of People Design, that organization architecture defines the allocation of authority. The formal organization chart is just one layer of organization architecture. Cross-functional workflow groups and project teams are two other layers. To delegate power, advance organization knowledge, set direction, and maintain execution disciplines, it is necessary to understand the interplay among formal structure, workflow groups, and project teams.

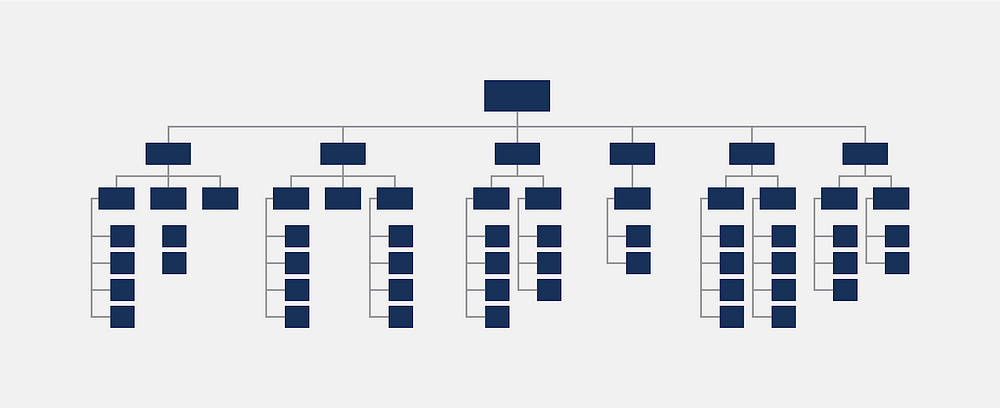

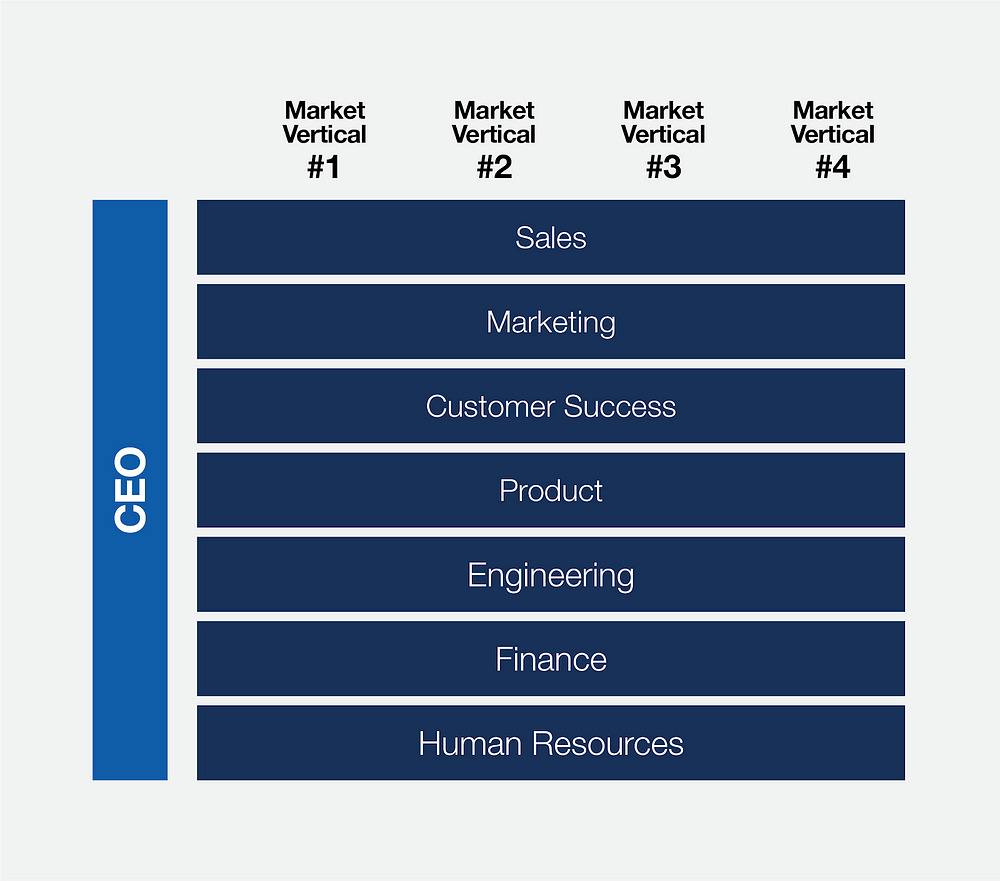

A typical formal organization chart may look like this:

But once we introduce the notion of cross-functional workflow groups and project teams, the picture is more nuanced:

Let’s focus on the typical organization chart for our exploration of a horizontal vs. vertical structure. For some, “horizontal” equates with “flat,” and “vertical” equates with “tall.” Flat organization structures are usually more flexible, self-organizing, and empowering than more hierarchical structures. Flat structures are often the best choice for tech companies that need to respond quickly to the dynamic reality of tech products and markets.

Beyond flat or tall, there is another way to define horizontal and vertical organization structures. In this meaning, “vertical” refers to “market vertical,” and “horizontal” refers to “cutting across market verticals.” In a vertical structure, the market verticals comprise the primary organizing principle, with functions secondary. This contrasts with a horizontal structure, where functions are primary, and market verticals are secondary.

The result of this horizontal/vertical construct is a continuum of possibilities, from a highly verticalized structure to a highly horizontal structure.

Option One: Fully Verticalized Structure

The image above depicts the structure of a holding company, a conglomerate, or a highly diversified company. In such a company, the market requirements, business models, business unit lifecycle, and cultural requirements are so diverse from market vertical to market vertical that there is no benefit in sharing functions. Business unit general managers operate as de facto CEOs of their business units (in the extreme, these units get structured as independent companies). They exercise high levels of control and autonomy. In this model, even the brands of the business units are often bespoke.

The primary organizing principle in this structure is market focus. Everything subordinates to this objective.

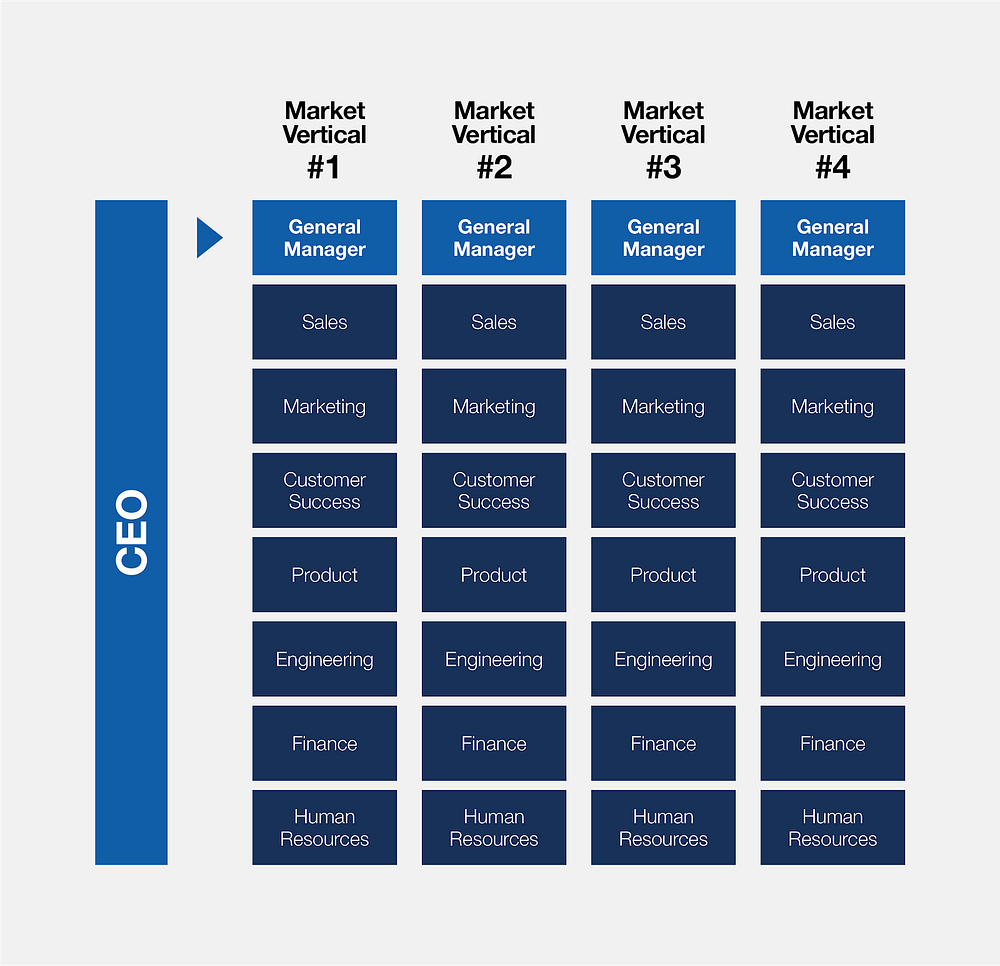

Option Two: Highly Verticalized Structure

The option shown above is similar to the first, in that the business unit leaders have significant autonomy and functional control. But budgets, hiring, and financial systems cut across vertical business units, ensuring a high level of centralized control.

This makes sense when the vertical business units are at similar stages in the business lifecycle, but still exhibit significant differences in product requirements, the business model, and revenue engine requirements. The primary organizing principle here remains market focus, but increased central control and efficiency emerge as secondary principles.

Finance and HR functions cut across the verticals and report to the CEO. In this structure, there is a risk that these functional groups act as bottlenecks if they prioritize the needs of one vertical business unit over the needs of others.

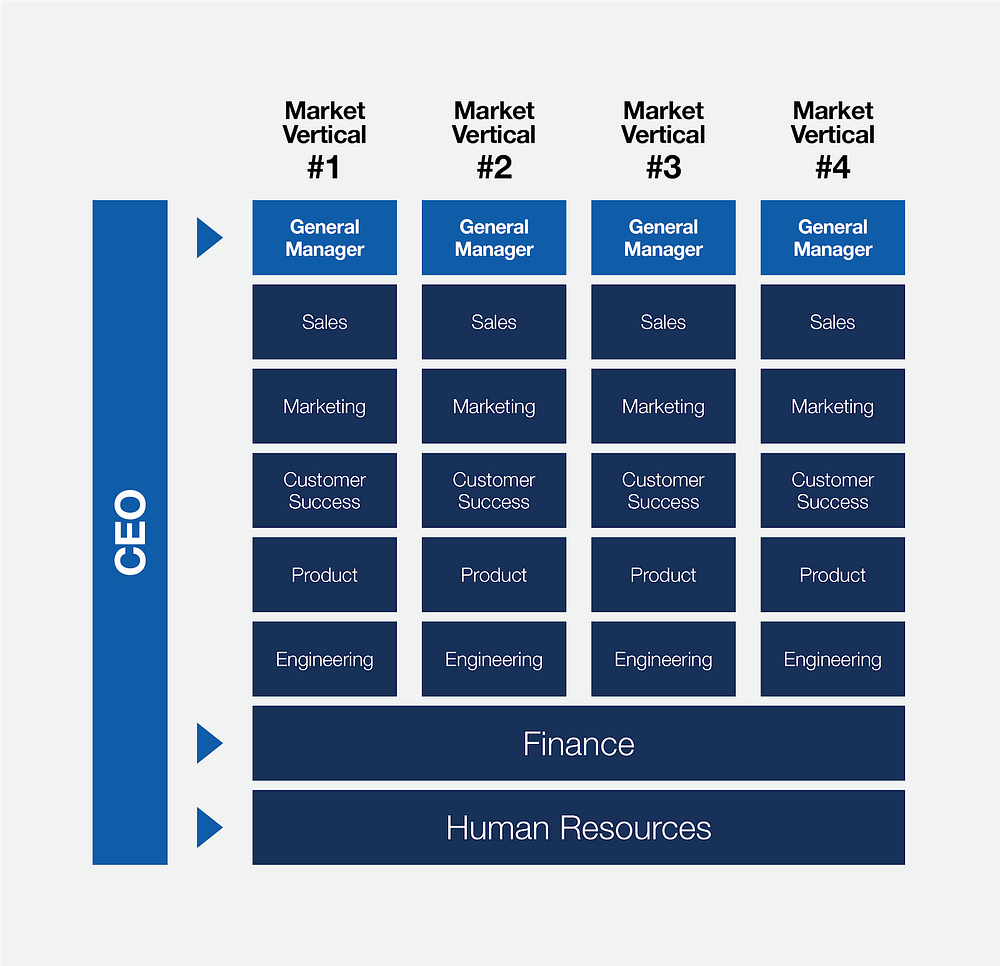

Option Three: Hybrid Structure

If you can serve all market verticals with the same or similar product platform, then it makes sense to organize product and engineering functions horizontally. This also ensures consistency in the marketing, sales, and finance tools stack. This structure is a solid choice when variations in the market verticals drive significant differences in segment personas, messaging, pricing, product feature requirements, sales structure, and go-to-market disciplines.

As a company scales, this option can support additional regional verticalization — for instance, North America, Latin America, Europe, and Asia — without sacrificing product, engineering, finance, and HR continuity.

This structure exhibits a balancing of organizing principles. Market focus remains central to the design. Sales, marketing, and customer success organizations uniquely serve these markets under a strong general manager who has dotted line access to resources in product, engineering, finance, and HR.

However, the design introduces a tension. Product, engineering, finance, and HR functions have horizontal leaders who strive for efficiency and continuity. The business units have vertical unit leaders who bring unique demands. This tension is healthy when the vertical and horizontal leaders aim for a balance between standardization and vertical-specific uniqueness. But there is also a risk of unhealthy conflict. The hybrid structure puts a premium on the collaborative capabilities of functional and business unit leaders.

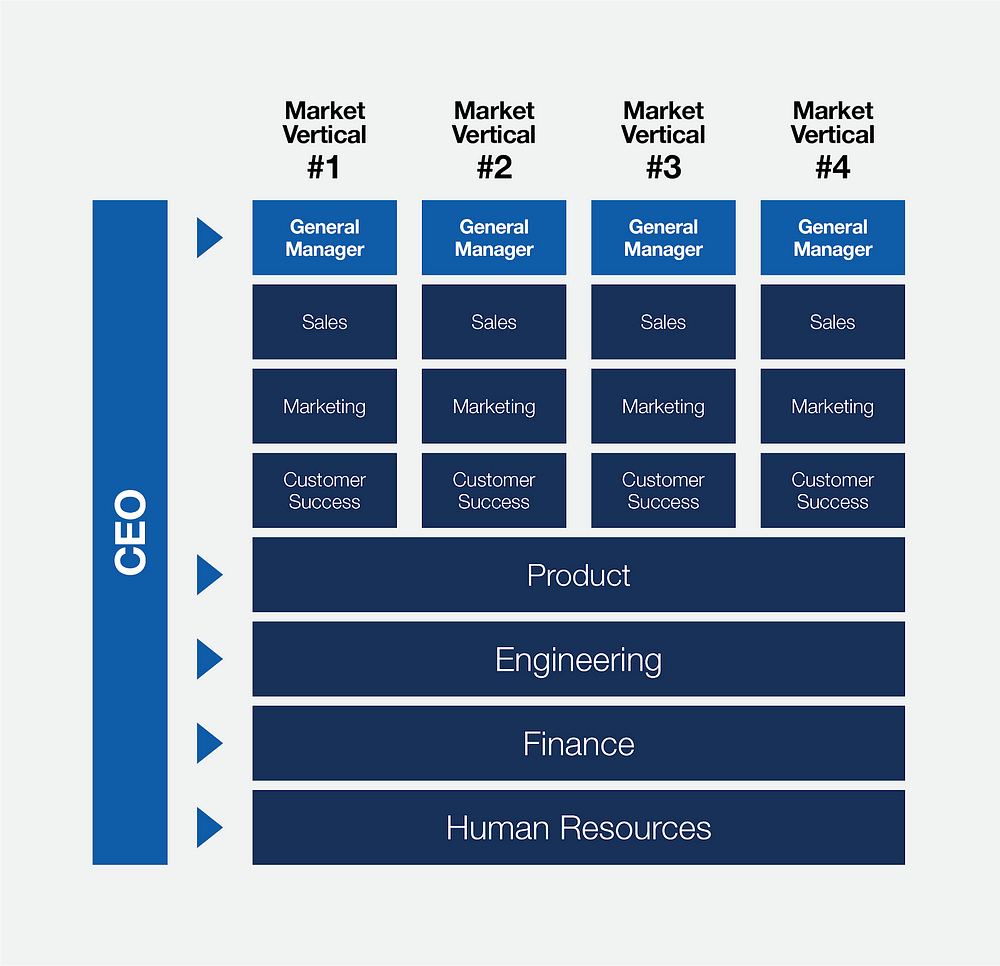

Option Four: Fully Horizontal Structure

In this structure, the differences between verticals are not significant enough to require unique organizational structures. One VP leads sales. So too with marketing, customer success, product, engineering, finance, and HR. In this structure, there still may be vertical assignments at the next level down. For instance, in sales, there may be directors or managers assigned to market verticals or regions. But functional continuity is the primary organizing principle.

This structure makes sense when the variations between market verticals are relatively modest. There may be unique product requirements, segment personas, and messaging, but the underlying value proposition, business model, and optimal go-to-market approaches are consistent.

The fully horizontal structure serves organizations with multiple market verticals where functional efficiency and control take precedence over market focus. Here, the risk is that as markets shift, the company might not notice the shift or might face structural rigidities that inhibit the capacity to respond. Of course, if your company serves just one market vertical and the variation between segments is minor, this structure is the best choice.

. . .

Joe and Vijaya assigned a senior product manager, a junior product manager, and five engineers full time to the task of retrofitting the platform for multi-vertical use. Vijaya advocated that Beatrice should lead this “Amplify Project Team,” and Joe agreed. Beatrice was ferociously customer-centric in her approach to product design. She took a get-out-of-the-office approach to product development; in the early stages of design, she lived in the customer’s work environment. She cared passionately about simplifying the user experience. As she often reminded the junior product managers who worked for her, “You have to walk a mile in the user’s moccasins if you want to find a better path through the forest.”

Within three months, Beatrice and one of her junior product managers visited over fifty boat, RV, and motorcycle stores, spending hours in each. Beatrice sat side-by-side with salespeople to listen and watch. She studied the composition of online consumer inquiries. She observed the steps salespeople went through to respond to the customer. She evaluated the product and pricing databases.

Eventually, it was clear that the key structural components necessary to render an automated price quote response in these new verticals mimicked the technical structure in automotive. The CRM systems in boat, RV, and motorcycle stores were entirely out of touch with today’s mobile, social, transparent reality. As in auto, the same human dynamics were also at play in these verticals. Consumers wanted product and pricing information before venturing into the store. The stores that could provide it rapidly and transparently built trust. With trust came higher store traffic and sales.

It took six months to make the product changes necessary to support new verticals. Beatrice couldn’t be sure, but she suspected that when the decision came to extend further into yet more verticals — such as furniture, heavy machinery, and other markets of interest — there would be few additional product features required. She made every effort to build into the updated product enough flexibility to support all future verticals. Time would tell.

At the end of the Amplify project, the product managers and engineers returned to their regular jobs. Victor and Serena agreed from the outset that the new verticals merited separate staffing. They assigned a product marketer and a growth marketer to a new Amplify work group, along with six SDRs and two inside sales reps. After some doubts, Serena agreed that everyone in the Amplify group — including the two marketing people — would report to a new Amplify revenue director reporting to Victor. The marketers would retain a dotted line relationship to one of Serena’s marketing directors.

Within six months, a steady stream of vertically-specific content was flowing out to prospects. The marketing campaign was brilliant. It made the boat, RV, or motorcycle salesperson the hero and poked fun at the many obstacles faced while trying to provide the customer with an excellent purchase experience. Soon, the Amplify group produced consistent sales results. With two SDRs for every inside sales rep, sales rep calendars filled with appointments. The close rate settled in at 40%. With that, Victor approved a rapid expansion: the Amplify team grew to two marketers, twelve SDRs, and six inside sales reps. As sales performance continued to accelerate, you happily approved Victor’s request for additional sales hires.

. . .

You may also enjoy previous chapters of People Design here.

And if these insights matter to you, please visit us at CEOQuest.com to see how we help tech founders and CEOs of startups and growth-stage companies achieve $10m+ exit valuation.