In the past three months, the temperature climbed steadily in weekly exec group meetings. You and the executive group were frogs in a pot headed towards boiling point.

The migration from independent business units run by specialists to an integrated, generalist-driven structure was stormy. The biggest problem was in marketing and sales. Previously specialists, the shift into generalist roles proved difficult for many. For example, a significant change in account assignments and workflows was necessary in sales. This disrupted pipelines, altered the pitch, and forced new product training.

Another problem was the new product teams — all three struggled in various ways to find their rhythm. The product teams introduced an ambiguous power dynamic. In this new structure, the functional groups were primary. All straight line reporting relationships reported to functional departments. The product team structure was secondary; it cut across the functional groups via dotted line reporting relationships to the product team leader — the VP Product for each of the three product lines. The new organization design depended on strategic buy-in, mutual understanding of both general and product-specific priorities, and a collaborative mindset among all executives and directors.

In the beginning, even Vijaya, VP Product for SparkAction CRM, struggled. She had two direct reports — both of them SparkAction CRM product directors. The other members of her product team — the Marketing CRM director, the Sales CRM director, and the Customer Success CRM director — were dotted line relationships. How precisely should that work? Disoriented at first, Vijaya soon found her footing. She knew Serena, Victor, and Bill well and trusted them. She sat down with each to develop a leadership development plan for every CRM team member. The plan included a monthly three-way coaching session (director, functional VP, and her) so that all directors received developmental feedback. Vijaya took her coaching responsibility seriously. She expected CRM product team members to be good ambassadors for the “end to end strategy,” as well as to advocate for the CRM product.

On the other hand, Ashley seemed lost. As VP Product for SparkInterest Web, she wanted to advance the integration strategy and liked the idea of a collaborative culture. Unfortunately, she had no feel for how to work this way. In her new role, the ability to influence was more critical than the ability to control. But her entire work experience was in top-down, command-oriented organizations, and she found it difficult to develop the skills and reciprocal relationships that the new strategy required. In your regular coaching sessions, you encouraged her to spend more time with Serena, Victor, and Bill to understand their priorities, and to share her own. She began to catch on, but in the meantime, the Web product line suffered. Improvement would take time.

Meanwhile, Pat Jansen, leading the SparkControl DMS team, was positively belligerent. Like the other two product teams, his DMS team comprised directors from sales, marketing, and customer success all with dotted lines to him. Pat tried to manage the team as if they were his exclusive direct reports. Within the team, he imposed a top-down, command-oriented decision style. Recently, he took to berating them for failing to deliver adequate support to the DMS product. As a result, the team was rife with dysfunction. Pat seemed to possess a zero-sum view of the world. The whole premise of the new strategy was anathema to him. For Pat, all that mattered was his DMS product. His attitude put a strain on many peer relationships. Especially for Serena and Victor, Pat’s frequent outbursts and overbearing demands went too far.

The timing could not have been worse. The board wanted you to engineer the final push towards IPO. So, you needed sales to be accelerating, not decelerating. You needed the strategy to be working, not failing. You needed your top executives to come together, not fall apart. The IPO path required a top-tier CFO with public experience, but your ill-equipped head of Finance wanted the job. Furthermore, you needed a fully supportive, aligned, and energized board — unfortunately, they had doubts.

In the last weekly executive group session before the board meeting, everything came to a head. Jack was in the midst of a review of tepid prior-month financial results when Pat suddenly jumped up. Shaking his finger right in your face, he said, “This is your fault. It’s your lousy integration strategy, dammit! My DMS product is caught up in this mess. Now when are you going to put this company back together the way it was meant to be, by business unit?”

Everyone fell silent, all eyes on you. You struggled to keep calm. You stood slowly. “Sit down, Pat.” Pat wavered, and then returned to his chair. “I understand, Pat, that you don’t agree with my decision to reorganize into an integrated structure. I know you didn’t buy into the whole ‘sum is greater than the parts’ idea. But that decision was made, and we are not going back. I said it then, and I’ll say it now. I expect you and every executive to support our strategy. Disagreement is fine. But when a decision is made, we all must come together to execute.”

You continued.

“Pat, I need you to work hard to make this reorganization successful. In particular, you need to work more collaboratively with Serena and Victor. The DMS product will be most successful when it is seen by our customers as a critical component in a comprehensive set of digital solutions. As far as I can tell, you’ve not shown much support for this broader product line, or the broader company, for that matter. You are a key executive, and for the strategy to work successfully, you have to commit yourself to it. Now in one week from today, I walk into a board meeting. By then I need to know that everyone is on board and committed. From today on, I expect that we march as one. Is everyone clear about that?”

Most nodded. Jack and Pat glanced at each other and looked away.

You walked out of the room.

. . .

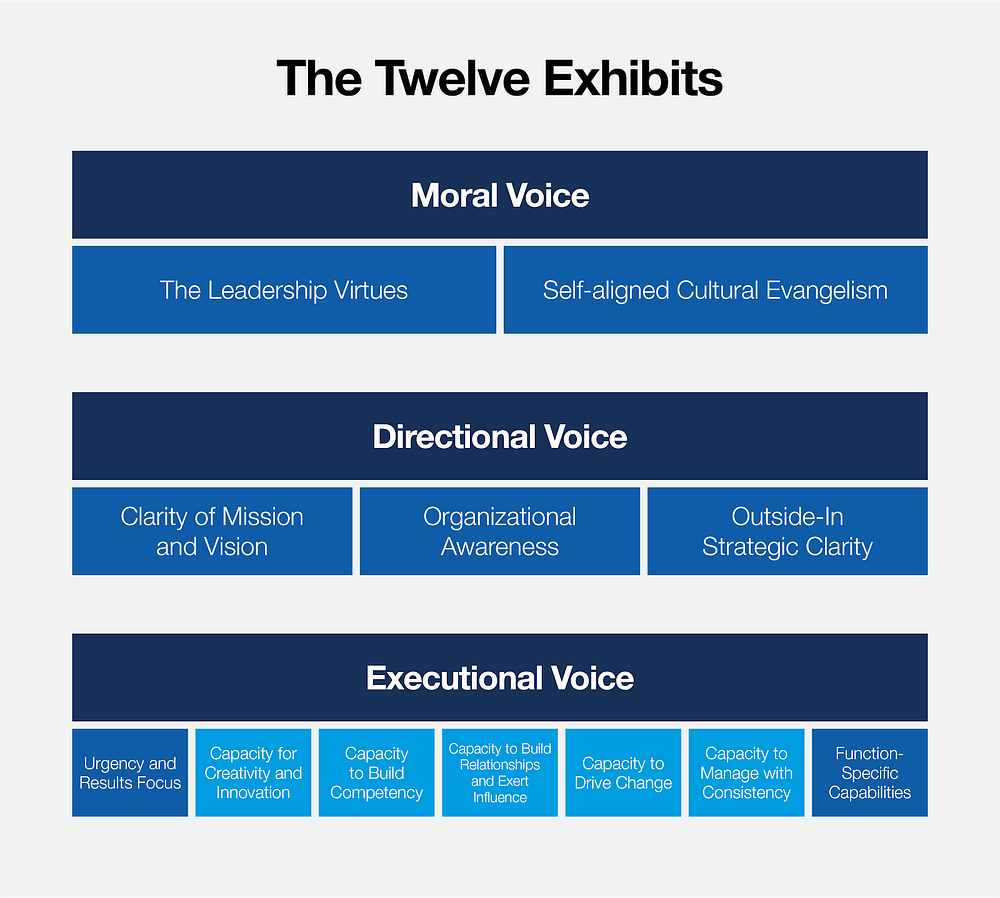

In Chapter 10, we introduced The Twelve Exhibits schema:

These are the essential leadership attributes. Each box in the schema represents a deep well of meaning and best practice. For instance, “Leadership Virtues” (the first box on the top left under Moral Voice) are the foundation of moral leadership. The leadership virtues are quality, caring, temperance, prudence, courage, and justice (see Chapter 2).

All seven leadership competencies shown in “dark blue” are fundamental. If you lack in any of these seven attributes, great leadership will elude you. As to the remaining five under Executional Voice, individual executives may or may not possess one or more of these, and that’s OK, as long as the executive group as a whole exhibits all of them.

A leadership staff richly endowed with the Twelve Exhibits is prepared to face emerging truth, define strategic imperatives, build strategies and plans, find and cultivate great people, communicate clear direction, mobilize strong daily execution, and create and manage teams that get big things done. Such leaders act with unimpeachable integrity. They accomplish extraordinary business results while protecting human dignity, advancing human development, and building a strong, sustaining culture.

In the heat of battle, how do you cultivate leaders such as these?

It all starts with you, the CEO. You are the role model (see Chapter 3). You shape the culture (see Chapter 7). You demonstrate by your actions how to build followership (see Chapter 8), how to share accountability (see Chapter 5), and how to charter and lead high-performing teams (see Chapter 6).

The most significant gift a CEO bequeaths to the future of her company is a leadership staff steeped in continuous leadership development. Leadership development is a system. Like any system, the creation and maintenance of it require proactive commitment from the CEO.

Development occurs at the three-way intersection of experiences, outcomes, and coaching. Challenge future leaders by coaching them through risk-bearing assignments assessed on outcomes and calibrated to drive continuous leader growth. Assignment by assignment, both success and failure are possible. Each creates a teachable moment. Failure teaches best.

A best-in-class leadership development system includes opportunities to stretch and challenge promising leaders. This is critical to understand. Growth only happens when people exceed their past expectations. No matter the assignment, ambitious goals must be set. As the leader pursues these goals, both quantitative and analytical feedback arises from performance results, the market, and peers and employees. Leveraging this feedback, the superior must coach the subordinate, exercising shared accountability by leveraging the principles of task-relevant maturity (Chapter 5).

In practical terms, advance leadership development with:

- Role-based coaching

- Project team leadership assignments

- New functional assignments

- Promotions

Let’s go through each.

Role-Based Coaching

The starting point for leadership development is role-based coaching — beginning at the frontline. A frontline supervisor is a coach of doers. If your company is to scale effectively, every frontline supervisor must be tasked to find future leaders among the group of individual contributors she leads, and develop them. One of those individual contributors soon becomes the next supervisor. The leadership development experience he gained contributes to his effectiveness in the new role.

And so it goes throughout the organization. Anyone who manages someone who supervises people is a coach of coaches. The leadership development burden grows as you move further up the organization. As a company scales, the health of your culture, quality of your workflows, and performance of your business depend on mid-management strength and the readiness of new leaders to excel when promoted. These outcomes derive from a systematic commitment to ongoing leadership development — from the frontline supervisor role all the way up to the CEO.

Leadership development follows a set of steps. The superior’s first step is to determine the subordinate’s performance in her current role. If performance is inadequate, then coaching must be entirely focused on uplifting that performance. This person is not yet designated a future leader.

But if the subordinate is performing well in her current role and shows potential for growth, the superior must then take four additional steps:

- Ascertain the next logical promotion

- Identify the key functional and “Twelve Exhibits” competencies required of that role

- Determine the subordinate’s current level of competency with each

- Prioritize which of these competencies to emphasize in development

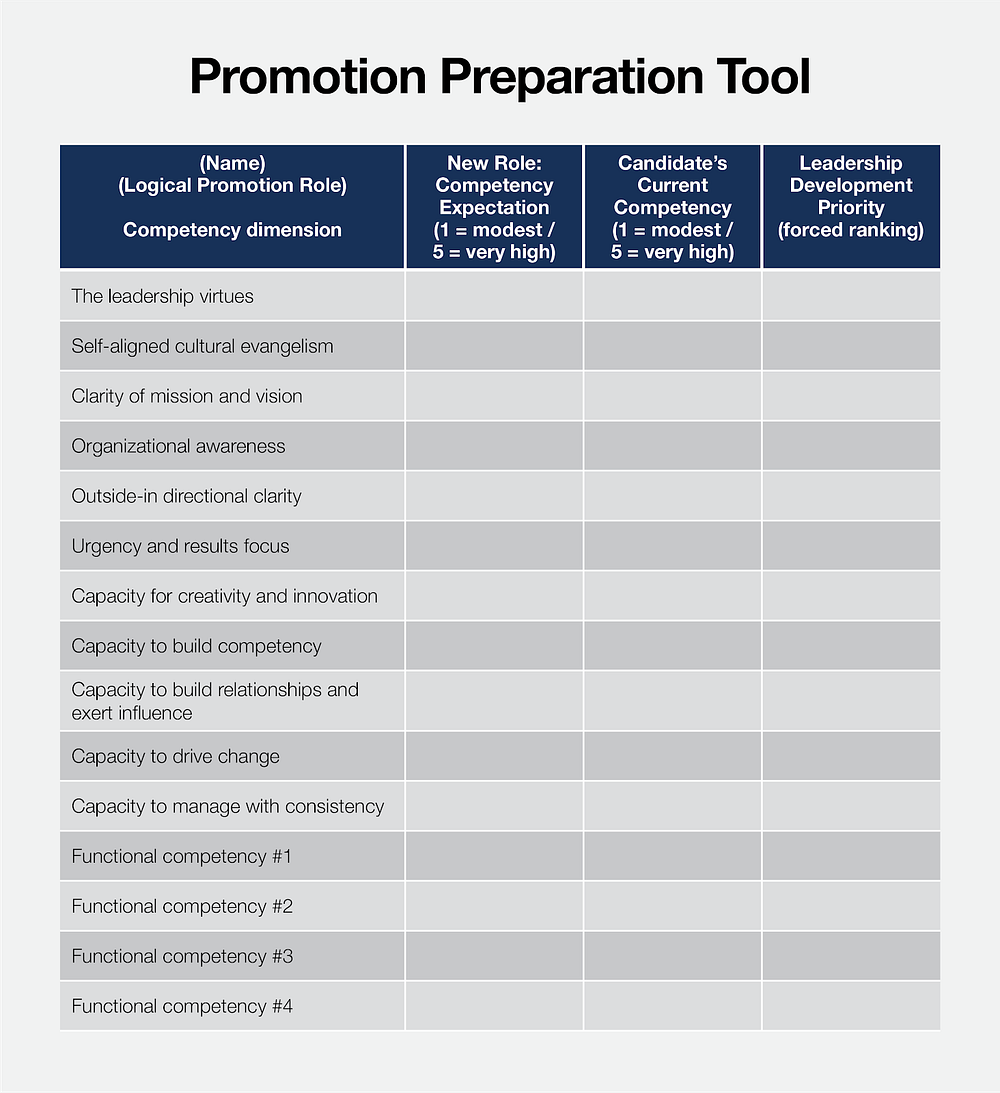

A simple Promotion Preparation Tool helps achieve this:

Given this level of clarity about the required areas of development, a supervisor leverages her one-on-one coaching sessions as the primary vehicle to question, challenge, encourage, and support her subordinate’s growth. Update the Promotion Preparation Tool and evolve the coaching focus based on the assigned experiences, challenges, and outcomes.

Project Team Leadership Assignments

Employees targeted for leadership development gain tremendously from effective one-on-one coaching by their superiors. However necessary this is in leadership development, it is never sufficient. Learning about leadership occurs in the doing. A powerful way to stretch future leaders at every level is to assign them the responsibility to lead projects. As discussed in Chapter 6, teams are mighty organizational units. Both success and failure are possible. The team leadership journey creates many coachable moments and affords superiors rich opportunities to assess leadership potential in subordinates.

Building your organization’s project management capacity is critical. Not only do projects drive change and growth, but they are also vital vehicles for leadership development.

New Functional Assignments

Another powerful tool in the leadership development toolkit is functional reassignment. The superstar customer success supervisor might become a sales supervisor. The promising senior software architect becomes a senior product manager. A high-potential marketing director might even become a sales director.

Reserve functional reassignments for only the most promising future leaders. They are risky. The maestro in one function is an apprentice in the next, at least initially. She may even prove incompetent. Despite the risk, the functional reassignment is an extraordinarily powerful leadership development experience. If the leader traverses into the new role successfully, she develops a much more holistic view of the organization, is better prepared for general management, and gains critical leadership confidence.

Promotions

Promotions are also a reliable vehicle for leadership advancement. You must ensure the candidate is ready before deciding on promotion. Assuming that is the case, the first ninety days are vital. During this time, the newly promoted leader establishes himself in the role with a new set of direct reports. In each direct reporting relationship, he reassigns responsibility and re-delegates authority. He re-establishes direction and executional disciplines. He refines his moral voice, made real in the tumult of daily work. Along the way, his superior must watch and coach.

The superior’s coaching support is pivotal in determining the newly promoted leader’s success — especially in the first ninety days. She shares full accountability for his success. In that shared accountability relationship, the essential thing she must do is to provide him with frequent, direct, and honest feedback.

The Promotion Preparation Tool is useful during this coaching period. As the superior, your job is to observe the leader’s actions and decisions. A periodic review of the Tool keeps your coaching focused on the competencies that matter most in this new role. Your reflections on the leader’s actions and decisions in the relevant areas provide rich fodder for coaching sessions.

Summary

Leadership development is a system that occurs at the nexus of experiences, outcomes, and coaching. As CEO, you must build and sustain the system. That starts by continuously identifying future leaders throughout your company. For each of them, you must design challenging experiences in the existing role and opportunities for project leadership, functional reassignments, and promotions. Then, you must confirm that superiors conscientiously observe and track the outcomes of the developing leader’s actions and decisions. Superiors should use this feedback in frequent formal and informal coaching sessions.

For the superior who is not practiced in providing critical feedback, it can feel difficult. So, too, for the recipient not used to receiving it. Even positive feedback can challenge some supervisors. Superiors and subordinates adapt when feedback is frequent, accurate, fair, and delivered with respect. As they do, the leadership development path opens, growth accelerates, and a company builds mid-management muscle ready to shoulder successful scaling.

. . .

The board meeting was underway for a half hour when, in the midst of presenting financial results, Jack said something that caught you off guard.

“These numbers show a significant negative sales impact from the recent reorganization,” he said. “Any recovery is going to take time. I think we may need to delay our IPO timing by at least six months.”

You looked sharply at Jack.

You and Jack always conducted board preparations together. In your final planning meeting with Jack, you told him that you would speak to the board about the weaker sales performance and its implications for the IPO. You wanted the board to know that it was taking longer than expected to realize the benefits of the reorganization and that sales suffered as a result. You intended to discuss the recovery plan and go over some new sales projections. And you meant to conclude that it would be best to move out the IPO timing by about six months.

But now Jack was delivering that message. And he did not refer to the recovery plan — just the delay in the IPO. As you quickly jumped in to describe the recovery plan, it felt defensive. You could sense it wasn’t going well. As you talked, Jack stared down at his papers while the board shuffled restlessly.

Halfway through your comments you stopped. “I would like to call the meeting into executive session,” you said.

The moment Jack reluctantly left the room, Aleksandr Brovic from Bain Capital spoke up. “OK, we get it. You think the strategy’s right, the reorganization will get fixed, and you can bring sales back soon. Magic. You just want six more months on the IPO timeline so that we go into it with a traction story. Right. But how do you get us confident that sales will get back on track? I’m picking up signals that you’re having problems with your exec team. Are all executives on board with your integrated strategy?”

You paused.

“Well, no. There have been some disagreements. I am seeking to build consensus, and get to deeper alignment, but there’s still work to do on that front.”

Sal Infante from Smash Capital piped up. “Well, you’re certainly correct about that. One of your VPs actually called me last week to complain. Did you know that?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“And I don’t sense Jack is on your side right now, either.” Other board members nodded.

Mark Goldstein from Imagination Capital weighed in. “So, let’s get this straight. We are preparing this company for IPO. Everything was going along swimmingly until four months ago when you entered into this reorganization. Because of strategic and tactical errors made by you and your team, we have been forced to push plans out half a year. That’s unacceptable. Your sales slowdown has to turn around immediately. And furthermore, you need to look at how you’re running the executive team. Something’s rotten in the state of Denmark. You don’t have the support you once did. You’d better get things back on track, and quick.”

As you walked out of the board meeting, shoulders slumped, Anik Kapoor smiled and tapped you briskly on the back. “Got a minute?”

“Yes,” you said.

“I think you should know who it was. It was Pat. He called every board member late last week complaining about the strategy. He made a case for the business unit approach — claimed it would double revenue growth rates. And he implied the company would be better off under his leadership than yours,” Anik said.

He continued, “But keep your head up, my friend. You’ve been through much worse than this. You’ll figure it out.”

. . .

Enjoy previous chapters of People Design here.

And if these insights matter to you, please visit us at CEOQuest.com to see how we help tech CEOs of startups and growth-stage companies achieve $10m+ exit valuation.