At multiple points along the way in the building of your company, either opportunity or necessity will lead you to contemplate an exit. Is it better to get out now, or press on towards what might be a better exit later? From whose perspective — you? Your investors? Your management team?

It’s a complex decision, fraught with promise and peril. Pity the CEO and board that passed on a sale in search of higher valuations, only to sell later for a fraction of the first offer. The process of building value and realizing liquidity is long and uncertain. The range of conceivable outcomes is wide. Risks abound. Interests compete. Stakes are high. Emotions run deep. Given that reality, how do you, the tech company CEO, navigate the ship?

In this chapter, we address the following:

- When to exit

- Stakeholder interests

- The perfect exit

- Exit scenarios

When to Exit

Your company’s value in the marketplace fluctuates over time. Your actual valuation is defined by the ultimate buyer, proven by the wiring of funds at close. Because any exit is a two-way transaction, your value is not a simple calculation of traction plus opportunity. It’s driven by the value that traction and opportunity brings to a buyer, and the degree to which multiple buyers must compete. Buyer needs and interests are as important as your performance and potential.

Strength of Company

The starting point, however, is your company’s performance. What is your traction? Opportunity is empty if traction lacks. If you have limited traction, the exit (if possible at all) will be valued at a low EBITDA multiple, discounted for risk — or based entirely on a buyer’s skeptical assessment of potential for future improvement. Solid traction, strong unit economics, high retention or repeat sales and predictable growth — these are four most important company performance factors.

Market Dynamics

Is it an emerging market, ready to explode? Or is the market mature? Does your company dominate, lead, follow or participate? Is your company gaining or losing competitive advantage? These factors will weigh on the buyer. If there is a lot of opportunity headroom, the market is expanding and your competitive position is strong, the market dynamics work in your favor.

Buyer Dynamics

Small companies can be bought by many companies. Big companies can only be bought by a few. The fewer the potential buyers, the more important it is to understand buyer motivation. Fear and greed drive buyers, but fear (via competitive disruption, loss of market share, etc.) is a great catalyst for action. If an enterprise buyer faces a known strategic gap (one that threatens the enterprise) that your company can fill, you are well positioned to claim premium value. Acquisitions also make sense when they add new revenue streams, open new verticals and build product capabilities. But the acquisition of your company becomes a strategic imperative when the enterprise determines it is in deep trouble without you.

Deal Competition Dynamics

At the end of a sale process, if there is only one interested buyer your only real leverage is “Go / No Go”. If you have two — or four — or six interested parties — then you have tremendous leverage in price and terms. This leverage dynamic is why it’s so important to organize the sale process to maximize likelihood that you have multiple suitors at the term sheet finish line.

Financial Market Dynamics

As we will cover in Chapter 15, private equity (PE) should not be overlooked as an exit option. PE is driven by financial market factors — the interest rate environment, the amount of money pouring into private equity, and the PE sector’s recent return performance. At the time of this writing, PE returns have been strong, capital commitments are at an all-time high, and interest rates are low. With lots of dry powder, firms are scouring the world for acquisition-worthy companies. As a result, the valuation discount normally associated with PE has disappeared. This makes PE an important target segment for companies seeking an exit.

Investor Dynamics

Your investors will have strong opinions on exit timing. If a VC firm has been invested in your company for more than four years, the investment may be pushing the edges of fund life. The fund needs its return on investment and thus fund dynamics may significantly impact the investor’s perspective on sale timing. For the investor that has just invested, however, a quick exit will likely deny them the anticipated return. For the investor that sits below more recent investors on the preference stack, her opinion will be governed by an assessment of whether exiting now puts her in the money.

If there are no extraneous factors at work, then investor views on timing will come down to the fear / greed dynamic. At every step in the company building journey, investors will make an educated guess on the outcome of an exit today, compared to an exit tomorrow. What upside will they miss? What risks will they avoid? Aligning interests among investors in the company can be challenging, if not impossible, in all but the strongest of exits.

Management Dynamics

Management has made an investment too. You and your exec team have invested your life energy into this company. Are you fired up, ready to conquer the next hill and take on the world? Or are you tired, beaten down by an endless succession of challenges? Are you paper rich but cash starved, unable to buy a house or a fancy car? Are you ready for a four-month vacation in Europe? Do you sense that your company looks attractive now, but could face risky headwinds down the road? Are your common shares or options likely to be in the money, or not?

These factors will impact how you and your team look at exit timing.

One key point. With regards to exit timing, it is your opinion as CEO that matters most: you’re the one who will drive the sale process, or keep scaling the company.

Stakeholder Interests

As a CEO, you have a fiduciary responsibility to maximize equity value for your equity holders. But to achieve this goal you must understand the interests of all stakeholders: investors, creditors, partners, management, employees, and customers. Let’s go through each.

Investors

The financial interests of investors are expressed in your cap table. Understand the voting and preference rights of each investor. Can one investor block the sale? What valuation expectation does each investor hold? Are all investors on the same page, or do different investors have different goals and needs? As CEO, you must understand these dynamics. You may need to apply advanced game theory to navigate the choppy waters towards a deal. It’s best to be clear about each stakeholder’s self-interest.

Creditors

The first money from an exit goes to creditors. Assuming it’s not a distressed sale, your bank will be happy to take its money and move on. Of course, if the company is in extreme distress it may be the bank that is executing the sale — as it seeks to recover what it can.

Partners

Business partners impact exit dynamics.

Some business partner agreements grant the partner a right of approval on a sale. Others may have negotiated the right of first refusal (ROFR) on an acquisition — giving them the ability to match your best bid. When the business partnership is fundamental to your company’s value, these two scenarios can be big problems at exit. They require you to disclose your intent to exit, and force you to pre-approve prospective buyers and terms with your business partner. In both these scenarios, the partner has an uncomfortably high level of deal leverage.

Another complication can arise with multiple channel partners, all of which compete against each other. If one or more are viable exit options, you will need to think through the stakeholder impact of all possible scenarios. Some partners may consider it anathema to buy a company that uses a competitor as a channel. Others may price a bid for your company under the assumption that a competitive channel relationship will end post-deal.

Address such scenarios proactively, in advance of the sale process.

Management

Like you, your exec team will be motivated to maximize returns at exit. If your company is growing quickly and the future looks bright, management will seek confidence the exit value maximizes rewards, discounted for risk. On the other hand, if your company’s likely exit value doesn’t exceed the preference threshold (i.e. common shareholders get nothing), then unless an incentive is put in place, management will have no interest in supporting an exit and will head for the door. This is why in distressed situations or where valuations are unlikely to cross the preference threshold, boards create management carve-outs. These incentives stipulate cash payments to executives if a sale is consummated.

At least in one sense, management has a built-in conflict with investors. When the deal is over, investors go away. Management usually stays. As you approach an exit, it’s important for you as CEO to negotiate your authority relationship and the management packages with the buyer. Make sure your team’s post-acquisition incentives are fully addressed and aligned.

Employees

In most tech companies, all employees have some stock options. Often, employees have an inflated vision of option value; even when common is in the money it’s not unusual for frontline employees to be disappointed by the size of the check at exit. Flight risk in the months following an exit is a significant problem. As CEO, you should make sure your most important employees have packages that attract them to stay on. Before an exit is announced, you should carefully prepare communications and individual impact summaries.

Customers

Customers are important stakeholders in an exit. Your customer must be reassured that you remain committed to them and their success. Does the acquiring company bring obvious benefits to the customer? Or does the acquisition put some of the customer’s reasons for buying your product at risk? In some situations, a customer becomes your acquirer. Are there collateral effects? How do other customers react?

Before you announce a sale, be sure to think through all possible customer implications, and ensure your communications plan addresses them.

The Perfect Exit

Yours won’t be perfect. But it’s good to know what the perfect exit and exit process look like.

2 Years from Close

First, know your value. To whom might you sell? Why? List all possible buyers — both strategic and PE. For each, develop your acquisition thesis. What strategic priorities drive each buyer? How do you fit in? Which buyers are motivated by fear? Which by greed? The more clearly you understand buyer motivations, the better.

The buyer acquisition thesis should address the following:

- Strategic rationale (strategic gap, vertical expansion, tuck-in, add-on, etc.)

- Specific sources of value to buyer (customers, product, channel, team, revenue engine, etc.)

- Degree of integration leverage

- Revenue and/or Cost Synergies

- Estimated degree of acquisition impact (modest / significant / transformational)

- Points of greatest traction leverage (what aspects of your business, if significantly improved, would drive maximum value acceleration?)

The latter point is especially important. You are two years away from your planned exit. If you can clearly isolate the business aspects that drive greatest value leverage, you can organize your strategic imperatives accordingly.

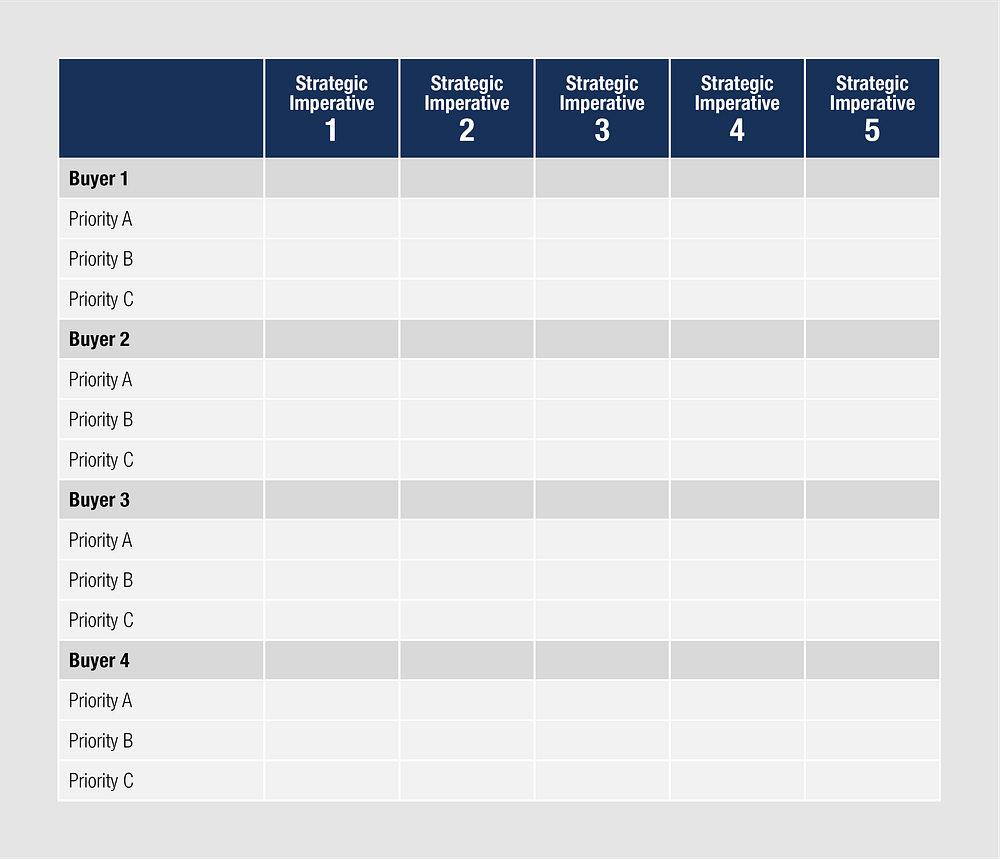

To confirm your own strategic imperatives are focused on the priorities that buyers will most value, check the boxes below wherever your strategic imperatives are matched with buyer priorities:

You should see lots of check marks. If you don’t, and you want to exit any time soon, update your own priorities.

Of course, it’s not enough to know your priorities. You have to pursue them effectively. This starts with talent. 24 months out, be sure that every member of your exec group is an “A” level talent. You need high performers in all executive positions.

Confirm deep strategic alignment. Is everyone on the same page, and is everyone clear on roles and deliverables?

Finally, make accountability core to your culture. Superiors should be meeting with subordinates consistently, to critically review performance and to ensure milestones are achieved. With 24 months to go before an exit, now is the time to turn your entire company into a high-accountability, high-performance engine.

18 Months from Close

Talk to bankers. Investment bankers exist to guide CEOs skillfully through the byzantine M&A process, resulting in a higher exit price and a higher likelihood of close. Having these conversations this early will help you identify the business drivers in your business that deliver maximum exit leverage, with time still available to work on them. You’ll also discover gaps in your story, broaden your vision for alternative exit pathways, and come to terms with the magnitude and length of the process. Just don’t expect to receive from these conversations a realistic estimate of the exit price. Bankers often estimate high, believing, with some justification, that doing so wins engagements.

At the highest level, a buyer’s acquisition thesis is essentially always driven by arbitrage and long term profit maximization. This dynamic means buyers (with limited risk tolerance or synergy potential) either buy on EBITDA multiples, or based upon the ability to leverage their own resources to invest and realize a superior return, also known as strategic leverage. Depending on which swim lane, the entire approach is different. An EBITDA multiple exit typically requires an auction process to maximize value. A strategic leverage exit requires a highly customized process, conforming the story to the unique strategic imperatives of different potential buyers. So when deciding on your banker, start with a realistic assessment of what the market is going to value in your business, and which type of process will best maximize value.

Here are the other key banker attributes to consider:

- Has a strong personal reputation — both for effectiveness and integrity

- Has extensive closed deal experience — multiple closed deals per year (validates experience with deal complexity and currency in deal terms, valuations, etc.)

- Deal experience includes many deals in your expected exit valuation range

- Works for a firm with a strong reputation

- Knows the market your company serves

- Has experience and familiarity with your company’s business model

- Has the strategic agility to understand how your company disrupts the market, challenges legacy players and beats out other competitors

- Can identify a comprehensive list of target buyers in and around that market

- Can identify all relevant PE firms, given stage, domain, business model and company performance

- Has an efficient, thoughtful process for engaging prospects

Integrity is the hardest attribute to confirm, but perhaps the most important. A banker’s incentive is to get any deal done. But your incentive — and that of your board — is to get the right deal done. If the right deal can’t be achieved, a high integrity banker will be the first to acknowledge that and support your decision to delay or to keep searching.

Bankers are compensated by an engagement fee and a contingent success fee, and typically require a “tail” provision — the period of time post engagement during which the fee is still owed upon a close of sale. The engagement fee usually ranges from $50,000 — $100,000. Sometimes it’s creditable at exit. The success fee is the percent of deal consideration. Sometimes it’s fixed, often in the 1% — 3% range, depending on deal size. Sometimes it has a sliding scale with breakpoints based on valuation outcomes or exit timing factors. The tail is typically a year, but can be less or more.

By 18 months from close, you should also begin actively pursuing strategic buyers — not to sell your company, but to propose business relationships that will elevate your company’s profile and strategic relevance to your buyer universe. This could be a channel partnership, or perhaps a strategic investment. Meet the CEO at a trade show. Talk with corporate development about investing in your company. Time in front of key executives at prospect buyer companies tills the soil of a future deal.

It’s also important to make sure your cash position is strong. By the time you are 12 months from exit, you will want to have 18 months of cash runway. So if another round is required to get there, now’s the time to mobilize a funding event.

14 Months from Close

You’ve now met with many bankers. Choose one.

At this point, you should have 20 months of cash runway.

12 Months from Close

Begin to architect your story. If yours will be an EBITDA multiple story, then of course the emphasis will be on traction, evidence of predictable returns, and risk in your forecast. If yours is a strategic leverage story, then your story will look similar to a funding pitch story — see Chapter 4, Investors Buy Stories — tailored to each prospective acquirer. Every claim needs to be supported by facts and annotated assumptions. As you develop the pitch, you will need to update and scrub your financial plan. Stress test every assumption. Make the plan real and reasonable.

It might seem surprising to work on your story (the pitch and the financial plan) so early. But there’s an important reason to do so. As you update the financial plan and craft your traction and opportunity story, you are forced to confront your weaknesses. With weak points highlighted 12 months from close, you still have time to fix them.

The data room should be coming together at this point.

You should have 18 months of cash in the bank.

9 Months from Close

First connections to prospective buyers (both strategic and PE) begin now. Your banker will reach out to every prospect per the agreed strategy, arranging calls to provide a high-level overview of the company and to gauge interest. Follow-up calls are arranged to answer basic questions. For those who remain interested, in-person meetings with you (the CEO), and your team are held.

7 months from Close

To the extent a more formal auction is merited, the banker alerts all interested parties as to the deadline for letters of interest. These letters are received a couple of weeks later. Prospective buyers who demonstrate reasonable expectations and interest are asked to sign an NDA and are provided full access to the data room.

6 Months from Close

The banker sends out the call for term sheets. If multiple term sheets are received, the final stages of the auction process begins. Terms and valuation are adjusted in an auction process until a winning bid emerges. The winning term sheet is finalized and signed.

Final 5 Months leading to Close

Due diligence proceeds, along with preparation of final closing documents. Management packages are negotiated. Synergies are identified, and a post-integration financial model is finalized. In the case of a strategic acquisition, plans proceed for the post-acquisition integration of the company. A communication plan is developed.

Close

The cash is wired into the bank account, to shareholders directly, or to a paying agent who will manage distribution of funds. Following the cap table and other agreements, proceeds are distributed. Multiple people, including you, plan your trip to Europe.

Scenarios

Of course, the perfect exit is rare. Here are two less-than-perfect scenarios.

The “Sell Early” Scenario

Sometimes early stage companies gain enough traction to be viable and interesting, but not enough traction to be a stone-cold home run. When doubt about the future creeps in at the board level, or for the CEO (or both), pressure can build to sell early.

For the company somewhere on the journey from MVC to MVR, an early sale introduces a number of challenges. You must manage the process alone — no banker will work with such a small company. Depending on buyer dynamics, you may have limited leverage. For the buyer, the acquisition thesis at this stage can be an “acquihire”, a “tuck-in scale acquisition” or a “small strategic scope acquisition.”

Acquihires are rare, and with few exceptions transact for very low valuations. The buyer simply places a value on the time savings to hire your team all at once, as compared to having to search for and find similarly qualified people.

Tuck-in scale acquisitions are those acquisitions that bring modest incremental value to an acquirer’s existing product. Once again, the buyer compares the benefit of gaining this incremental value now via acquisition, versus spending additional time to build it. The buyer has the most leverage. Tuck-ins tend to transact on low EBITDA or revenue multiples.

In both cases, your investors may make little or no return. In such a situation, nothing is left for common shareholders. But of course, to even get the deal done, the support of management is required. For that reason, boards usually negotiate a management carve-out. This provides management (especially you) the incentive to stick around and get the deal done.

The third possibility is that the buyer sees meaningful strategic value and integration leverage in your product and is willing to take on more risk (in terms of the early stage of your company), so as to buy at a lower cost. You have somewhat more leverage in this type of acquisition, especially if there are multiple prospective buyers.

When you sell early, it is especially important to enter the sale process in a strong cash position (at least 12 months of runway). Horror stories abound of startups left at the altar after a six-month, all-consuming enterprise sale process — followed shortly thereafter by financial ruin.

The “Sell or Close” Scenario

Sometimes your company’s value is so in doubt your board presents you with a “sell or close” fiat. Usually, this involves a set timeframe to get a deal done. No deal, no company — investors will push the company into bankruptcy and sweep and distribute any remaining cash.

When you’re in this situation, it’s a five-alarm fire. Your best people will be streaming out the door — either because of a forced downsizing or because they’ve lost faith. The value of the company will seem to have a weekly radioactive half-life.

If you’re the CEO in a “sell or close” scenario, it’s entirely appropriate for you to negotiate a solid carve-out package. You’ll be carrying the company on your back all by yourself, and your odds of success will be low. Make sure that if you do succeed, it’s worth it.

. . .

To view all chapters go here.

If you would like more CEO insights into scaling your revenue engine and building a high-growth tech company, please visit us at CEOQuest.com, and follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter, and YouTube.