Digital technology has hit an inflection point, and there’s no turning back. Products and services are digitizing. More and more human activity is becoming automated. Data guides the optimization of everything; analytics have moved from descriptive to predictive to prescriptive to cognitive. Business models are evolving as companies adopt subscription, marketplace, e-commerce and advertising based models.

The successful enterprise can no longer just rent technology to improve what it’s already done. It must bring digital into its very center — to become a digital technology company. For larger companies, this will even require a willingness to disrupt themselves before others disrupt them.

The shift enterprises must engineer is not only in the area of software development and management. Everything must change. It requires a new culture, a new set of skills, a new set of tools, a new way of strategizing and a new way of thinking about the core value proposition of the business. It requires a whole new leadership paradigm. Follow along as the journey begins:

- The digital revolution

- Implications of rising digital change

- Business eras and leadership paradigms

- The problem with the structural-functional paradigm

- A unified theory of leadership for the digital era

- The Loop paradigm

The Digital Revolution

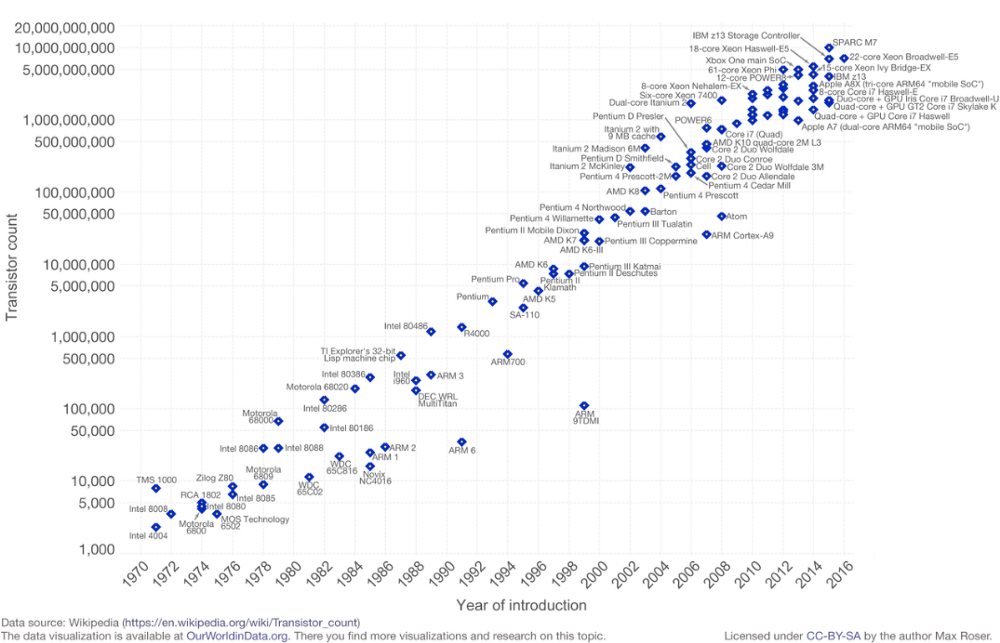

The digital revolution dates back to a Bell Labs invention: the point-contact transistor, invented in 1947. Shockley’s junction transistor quickly followed in 1948. The transistor replaced cumbersome vacuum tubes, enabling the rise of ever smaller, ever more powerful computers. Since then, integrated circuits and the transistors they carry have followed Moore’s law (Gordon Moore was co-founder of Fairchild Semiconductor and CEO of Intel), roughly doubling computing power every two years.

Moore’s Law: The Number of Transistors on an Integrated Circuit Doubles Every Two Years

Source: Wikipedia

The invention of the transistor spawned a Cambrian revolution in digital computing and global communications that continues to this day. The Internet has its origins in 1968, when the first TCP/IP message was sent. Atari launched its first digital arcade game, Pong, in 1972. The drumbeat of change has rolled on ever since: the first laying of optical fiber, 1G cellular communications technology, the first mobile phone, Microsoft’s founding, Apple’s founding, the Walkman, MS-DOS, floppy disks, the Commodore 65, the compact disk, the first modem, IBM PC, the Mac, the rise of the World Wide Web, 2G, Linux, email, search, Yahoo.com, Google, DVD, USB, Skype, Facebook, co-location, cloud computing, software as a service, Salesforce.com, platform as a service, 3G, infrastructure as a service, Amazon Cloud, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud, the iPhone, mobile GPS, 4G, big data, artificial intelligence, machine learning, blockchain, bitcoin, autonomous vehicles, 5G, Internet of Things and quantum computing (just to name a few). Today, with access to networked servers, companies have access to virtually limitless computing power and storage. The revolution continues unabated.

Implications of Rising Digital Change

We used to talk about “technology” companies as compared to “non-technology” companies. As recently as a decade ago, a non-technology company leveraged technology simply to enable processes. A new CRM system, ERP system, accounting system, payroll system or record keeping system helped it do the same thing it had always done more efficiently.

But in today’s world, every company of meaningful scale must be a digital technology company. Not a technology-enabled company — a digital technology company. Today’s enterprise must bring digital technology into the center of its being. Without digital leverage at the core, an enterprise will fall behind and be overrun.

The company with digital leverage brings digital technology into its products, services and internal processes to make them better. For products, this might be expressed in a compelling ecommerce experience, online marketplace, online media website or SaaS platform offering. Wherever digital capability can deliver leverage, products and processes are made better — from simple workflow automation; to clean web user interface design; to mobile first design; to big data solutions; to machine learning, AI and robotic process automation; to reactive platforms built via microservices architecture residing on the cloud; to advanced cybersecurity. That’s digital leverage.

To succeed, such an enterprise must be fit in all its systems. Even companies historically described as technology companies can fall behind. The pace of change is unrelenting. New digital technologies open up new capabilities that create new openings for competitors. Markets, with their segments and personas, are continuously evolving. Their needs drive ever-increasing demands for product feature customization. React slowly and a competitor will step in. The company that can’t regenerate and adapt to these forces is at risk. The only way to keep ahead is to be a fit systems enterprise with digital leverage at the core.

Consider the digital revolution’s effect on historically non-technology companies. Restaurant chains have been brought to account by social media. The music industry has been disrupted by iTunes. Auto manufacturers have been tested by the rise of autonomous vehicles. Financial institutions have been threatened by FinTech innovators, such as SoFi. The taxi industry has been battered by Uber and Lyft. The hospitality industry has been disrupted by AirBnB. Retailers have been traumatized by Amazon and eBay. Newspapers have been pushed to the edge by CraigsList and Google, and the digitally-driven decline of brick and mortar retailers.

Even large “technology” companies have needed to continuously reinvent themselves. Apple almost collapsed into bankruptcy before Steve Jobs returned to save it. Hewlett Packard has struggled to transform for years, stumbling into a series of ill-conceived mergers and then fracturing into parts (first Agilent, and then the split of HPE from HP Inc.). Oracle is burdened with a revenue mix heavily dependent on legacy products threatened by upstarts, and faces increasing competitive risk.

When Satya Nadella became Microsoft CEO in 2014, it too was at risk — stalled in innovation, overly dependent on its legacy products (especially Windows) and losing its best people. Beginning as leader of its Server and Tools business, Nadella rebuilt employee trust and strengthened the culture. He refocused priorities to concentrate on Azure Cloud. Azure now owns 30% of the Cloud marketplace, driving around $30B in revenue for Microsoft and digging deeply into AWS. As CEO, Nadella has reinvigorated xBox, grown the Surface line of laptops and devices, put Windows 10 back on track and invested in bold experiments in quantum computing.

For technology startups, the path to success is fraught with risk and difficulty. For every Google, Microsoft, Apple, Uber, AirBnB, Pure Storage, Salesforce.com and Zuora, there are thousands of companies that fail early, cap out or exit before achieving breakout success. The best tech startups are the ones that focus maniacally on their customers while simultaneously gaining digital leverage in their products and processes. They continuously innovate and optimize in service of evolving needs.

The point is that even “technology” companies struggle to accelerate growth, regenerate and stay ahead. For the historically non-technology company, the challenge is even greater. Lacking tech DNA at the core, such companies face an expensive, risky multi-year digital transformation. Worse, top leaders don’t know what they don’t know — they lack a roadmap, and lack the right mental model.

The good news is that examples of successful transitions do exist. Early in the rise of the Internet, the New York Times devoted itself to digital transformation. It built an online subscription-based business. It established digital partnerships. Today, digital revenues at the New York Times exceed $500M, more than the digital revenues of the Washington Post, BuzzFeed, the Guardian and other major online publications combined. Fidelity, founded in 1946, has successfully advanced its digital first strategy. Its mobile app boasts a 4.7 rating and half a million reviews on Apple. Disney has introduced IoT into its parks (a $1B investment). It has created RFID wristbands for all guests that serve as a payment tool, a hotel room key, a park access badge and a ticket for rides. Disney uses its data to optimize for crowd control, and to identify which park experiences are in highest demand. Walmart has invested heavily in Walmart.com and the end to end digital experience, as it seeks to compete with Amazon for the online retail dollar. It’s also bought up online brands like Jet and Mod Cloth to round out its offerings and extend its digital footprint.¹ Kaiser Permanente has built digital leverage into its health care operations.

These are just a few examples of historically non-technology enterprises that have brought digital technology to the center. But what does it take to pull off this transformation? Yes, there are a set of investment decisions to make. But it goes deeper than that. A fit digital technology company is led differently.

As digital change has accelerated, the human beings running enterprises have struggled to keep up. Most CEOs still organize, staff and lead their enterprises in much the same way as they did twenty years ago. Today’s business leaders grew up within a structural / functional leadership paradigm. Most still live there. It worked well in 1999. But this paradigm is woefully insufficient for today’s technology-at-the-center enterprise.

Business Eras and Leadership Paradigms

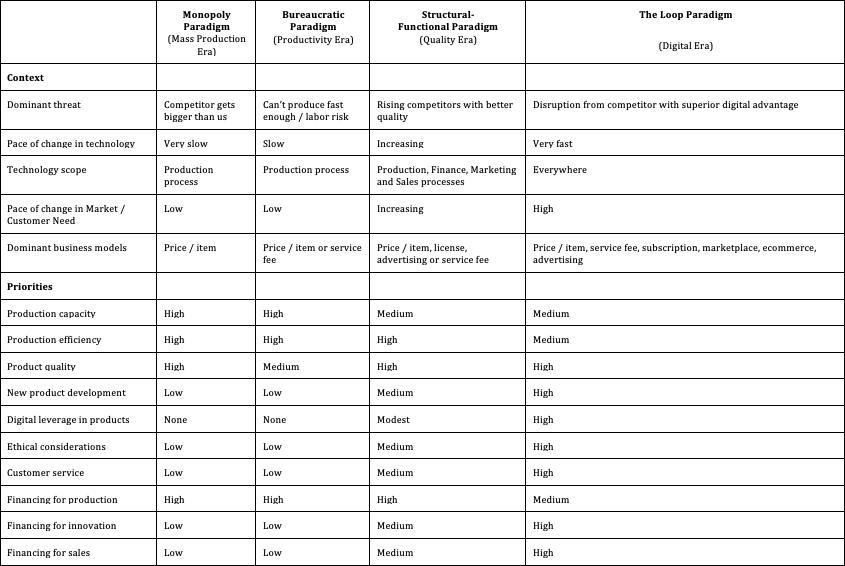

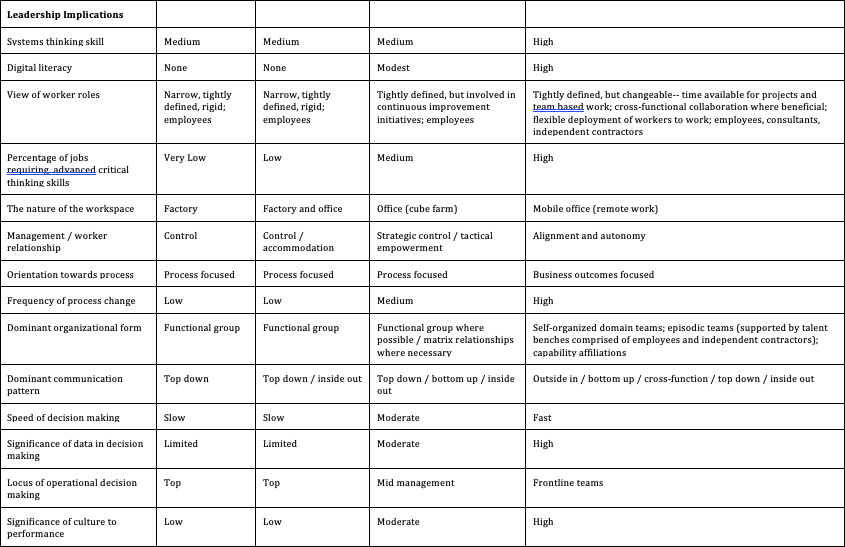

Over the past 100 years, there have been four business eras. Each era is defined by a predominant enterprise focus. For every era, a new leadership paradigm has arisen to meet its demands.

Mass Production Era / Monopoly Paradigm

First came the mass production era, in which industrial companies produced standard products at massive scale. During this era, enterprise systems were designed for scale. The era stretched from the early 1900s until WWII. Rising access to electrical power and petroleum sparked sharp productivity gains in manufacturing, enabling the big to get bigger. By 1939, 42% of all US manufacturing assets were controlled by the 100 largest corporations (SOURCE: Niemi, Albert; US Economic History, 2nd ed., Chicago: Rand McNally Publishing Co., 1980). This era required a monopoly leadership paradigm: leaders designed processes for efficiency, built dedicated supply chains, specialized tasks, treated workers as widgets, controlled worker behavior, sought market domination and pursued monopoly power. Leaders were influenced by the work of Frederick Taylor, whose research into what he termed scientific management led to optimizations in process. Taylor advocated specialization of labor, and tight specification of worker placement and physical movement on the assembly line to achieve optimal labor productivity.

The Productivity Era / Bureaucratic Paradigm

Leading up to and during WWII, US factories mobilized to support the war effort. After the war, they were still standing. These enterprises were well positioned to replenish a world depleted by war, led by leaders who brought a military leadership paradigm back to the business. But the rise of unions changed the relationship between management and labor. The scientific management movement was discredited. For incumbent enterprises, markets weren’t the problem — they were rich with opportunity. The problem was how to achieve labor stability and increase productivity so as to serve these markets. This era, the productivity era, is characterized by leaders focusing inward. Enterprise systems were designed for efficiency. It required a bureaucratic leadership paradigm, in which top leaders organized for control, designed the supply and production chain for productivity and bartered for labor peace. Production — not product quality — was the priority. Late in the era, new ideas regarding the relationship between management and labor began to emerge. Douglas McGregor’s The Human Side of the Enterprise (1960) introduced the concept of Theory X and Theory Y, the latter being the theory that workers could become intrinsically motivated to do good work if work and workspaces were designed with the worker in mind.

The Quality Era / Structural-Functional Paradigm

By the mid-nineteen-eighties, large manufacturing enterprises, who in many cases had been churning out high volumes of low-quality products, began to encounter rising competitive threat. For instance, Toyota, Nissan and Honda entered the US, built superior automotive products and stole market share from incumbents. Manufacturing firms were soon forced to concentrate on quality. The focus on quality led to attempts at closer management / worker collaboration and improvement of working conditions. The Total Quality Management (TQM) movement, promulgated by Edward Deming,² spawned a generation of Quality Circle teams at enterprises large and small. It also led to a quest for greater efficiency. Manufacturers began to shift operations offshore in search of cheaper labor. At the same time, the industrial, goods-based economy was beginning to make way for a rising services economy. Service providers (in retail, banking, communications, media and other consumer services) gained scale by focusing on the customer service experience.

This period, from the mid eighties to the late nineties, can be referred to as the quality era. Enterprise systems were designed for quality. In this era, leaders adopted what I call the structural-functional leadership paradigm. The term “structural-functional” emerges from the field of sociology. Emile Durkheim was one of the leading adherents of the structural-functional view. Here’s a description (from Wikipedia):

“The central concern of structural functionalism is… explaining the apparent stability and internal cohesion needed by societies to endure over time. Societies are seen as coherent, bounded in fundamentally relational constructs that function like organisms, with their various… social institutions… working together in an unconscious, quasi-automatic fashion toward achieving an overall social equilibrium…. The individual is significant not in and of himself, but rather in terms of his status, his position in patterns of social relations, and the behaviours associated with his status. Therefore, the social structure is the network of statuses connected by associated roles(emphasis mine).”³

When applied in a business leadership context, this paradigm is guided by six attributes of the leader’s mental model:

- Find stability

- Increase predictability

- Improve quality

- Improve efficiency

- Optimize the supply side

- Seek stable growth

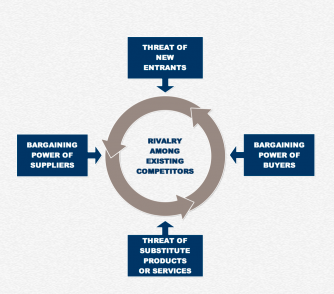

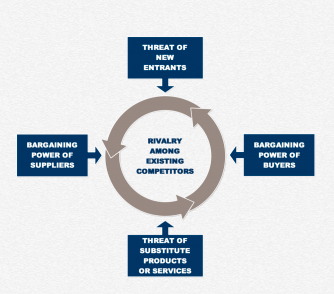

In his book Competitive Advantage (1985),⁴ Michael Porter presented a marketplace construct positing five forces that act on the enterprise. It captures the structural-functional worldview:

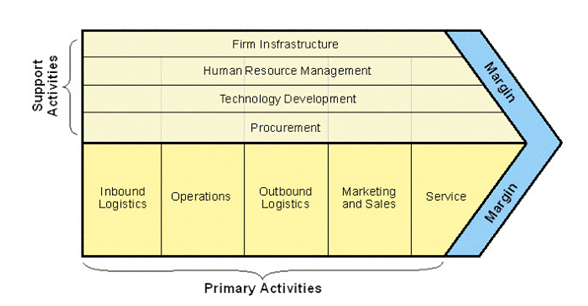

In this schema, the enterprise seeks to gain competitive advantage by optimizing the supply side, pricing and product improvement to keep ahead of competitors. Porter conceived of the enterprise as a value chain, as follows:

In Porter’s value chain, he differentiates between primary activities and support activities. Note the absence of product discovery and product management in his model. These two value creation activities don’t even exist.The model makes the assumption that existing product value is so significant and persistent it does not require mentioning. The value chain’s focus is on quality and internal process optimization, not the creation of new product value.

In the structural / functional paradigm, the enterprise is seen as a system — but the system is viewed in function-centric terms. Functions roll up to functional leaders. Processes may work within or across functions; if the latter, jobs are designed to minimize handoffs. In the traditional structural-functional view, the organization chart looks something like this:

A matrixed structure may exist in certain parts of the company where necessary to achieve collaboration, but in the power structure of the enterprise, functions and their leaders are primary.

If you want to learn about the prevailing leadership paradigm of a given era, read the business books of the day. Every generation of executives is influenced by the books published in the years leading up to their assumption of executive status. These books are not just helpful for what they say. They also speak in what they don’t say. Paradigms are basic assumptions about reality. When something that today seems important is absent from a twenty-year-old top-selling business book, it tells us something about the leadership paradigm of that time.

The Problem with the Structural-Functional Paradigm

In the eighties and nineties, the emphasis in business books was on choosing the right path towards excellence, connecting with customers, improving processes, organizing into teams for quality, managing people more effectively and becoming more innovative. Leaders were challenged to help their companies become customer-centric,⁵ matrix their organizations for better process coordination,⁶ become more team-based,⁷ become radically more efficient,⁸ become more innovative,⁹ and choose between customer intimacy, product leadership and operational excellence as your primary path to excellence.¹⁰

These exhortations reflect a world of moderate change. The structural / functional leadership paradigm was built for a world where markets moved moderately, enterprises scaled gradually, products changed slowly, customization was limited, brand reputation could be tightly managed, technology was an enabler and the pace of technology change was manageable. In such a world, functions might be rigid and monolithic, but they were efficient: “just do your job”. A control oriented leadership style could still work, even if calls for worker empowerment were rising: at least it created clarity of direction and expectations. Since most events followed a predictable pattern, cross-functional handoffs could be executed pretty well under pre-established rules. You might need a matrixed organization here or there to facilitate collaboration, but functions predominated.

In a world where change was gradual, technical systems could be built as monoliths — big and hard to alter, perhaps, but efficient. Architects and engineers had no choice anyway, given technology’s limitations at the time. Inside business processes, the goal was to reduce variation, increase efficiency and increase predictive accuracy. Change happened through big projects in a waterfall approach — so that all the interdependencies could be figured out up front. Function-centric, tending towards control-based leadership, with monolithic technology, monolithic organizations and a waterfall approach to change: that’s the structural / functional enterprise model.

It worked well until it didn’t.

In the nineties, as the Internet rose, leading business books paid scant attention to the potentially disruptive impact of digital technology — let alone how to mobilize to address it (one exception: Geoffrey Moore’s 1991 classic, Crossing the Chasm). The Internet was young. Technology was nipping at the edges, offering enterprises new efficiencies with CRM, ERP and accounting systems. But it wasn’t yet a threat to most companies.

But then everything began to change. The late nineties marks the rise of the era we are still in — the digital era. Starting in the late nineties and early 2000s, business books begin to confront digital’s disruptive impact. In 1997, Clay Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma distinguished between two types of technologies: sustaining technologies, and disruptive technologies. Enterprises are effective at leveraging sustaining technologies because they make processes faster, better and cheaper. But disruptive technologies pose an existential threat, he claimed, because the enterprise’s resources, processes, and values work against confronting the threat. To compete, enterprises should create separate innovation business units or acquire innovative companies, and leave them alone to do their thing.

Two authors from the early nineties were particularly prophetic. Crossing the Chasm highlighted the rise of the tech entrepreneur and put forward a game plan for technology disruption. Moore showed how entrepreneurs could move beyond the visionary early adopters and “cross the chasm” into mainstream markets, disrupting established enterprises. And Peter Senge, in his 1991 book The Fifth Discipline, showed how systems thinking (along with personal mastery, mental models, shared vision and team learning) helps leaders better see the integrated nature of things and lead more effectively in an increasingly complex world.

From the mid-nineties on through to today, business books have focused more and more on disruptive technology. Some books show a path for the disruptor; others address how large enterprises can respond. Moore followed Crossing the Chasm with Inside the Tornado, published in 1995. In this book, he showed how hyper-growth startups can migrate the technology adoption lifecycle in three phases. Through smart and aggressive competitive moves, the well-led disruptor in a category could emerge from the “tornado” (the middle phase) as the winner, ready to take a large percentage of the main street market.

In 2005, Steve Blank wrote Four Steps to the Epiphany, in which he identified the four stages of company building: customer discovery, customer validation, customer creation and company building. He advocated extreme outside-in thinking and continuous iteration until sure of product / market fit. This was followed by The Lean Startup, written by Blank’s former student Eric Reiss in 2011. In it, Reiss emphasizes agile development practices and data-driven validation of business models. Peter Thiel’s Zero to One (2014) identified characteristics of successful innovators. Great companies build a product pipeline that can deliver products featuring either 10X improvements in value at parity cost, or order of magnitude reductions in cost at parity value. Such companies are good at detecting trends and emerging technologies, and timing breakthroughs that leverage these to maximum effect.

Then in 2015, Moore re-entered the fray. With Zone to Win, Moore lays out a path for continuous innovation in the large enterprise. Enterprises must make investments in three horizons: current categories, break-out categories and future category options. Current category investments are the investments made in existing products to drive value extension. On the other end of the spectrum, he argues for making many small future category bets by investing in small independent teams chasing a product thesis, much as a venture capitalist would. The bet is that some of these innovation initiatives will prove successful; at that point the enterprise can invest more heavily into them and move them into the heart of the enterprise. By this means, the core enterprise can continue to milk its legacy products and meet quarterly earnings requirements while methodically sowing seeds of its regeneration.

Most recently in 2018, Tien Tzuo (CEO of Zuora) published Subscribed, where he demonstrated the rising influence of a new business model — the subscription model. He showed how this digitally enabled model has penetrated a growing array of industries and product categories.

These authors have made important contributions on the journey towards articulating the imperatives of today’s fit systems enterprise at every stage of company growth. Both entrepreneurs and large enterprise executives have benefited. Inside these books are important threads of thinking from which a new paradigm can be knit. But a digital change inflection point has now been reached, and there is no going back. The structural-functional paradigm needs to be replaced. The threads are there, but the knitting isn’t done. It’s time to bring them together into a unified theory of leadership for the digital era.

A Unified Theory of Leadership for the Digital Era

Let’s start with the end in mind. To be successful in today’s world, an enterprise must be both generative and adaptive in the face of change. The generative imperative is the need to create and capture new product value. The adaptive imperative is the need to become more resilient, scalable and efficient. The enterprise must advance these two imperatives by bringing competitively superior digital leverage to its products and processes. It must keep ahead of its market, and react and respond more quickly and effectively than competitors. I refer to such an enterprise as a fit systems enterprise.

What, exactly, does a fit systems enterprise look like?

It is generative:

- It has a powerful and virtuous vision for the future

- It has an array of sensors in the marketplace, providing continuous feedback about the evolving needs of customers, segments and personas

- It has a proven track record of leveraging market insight to achieve new product breakthroughs that deliver meaningful new value to large segments of customers

- Its products exhibit digital leverage, taking full advantage of technical innovations and wiring its products to provide a stream of data back to the enterprise regarding product performance

- It brings digital leverage and automation into every possible component of its revenue engine

It is also adaptive:

- It seeks to automate every low-variation business process by renting or building appropriate technology, and to continuously improve previous automations

- Where possible, its technical systems are built modularly as a set of small, loosely coupled services leveraging reactive microservices architecture

- Its data infrastructure is enterprise-wide and fine-tuned, driving data and analysis to the nodes of the enterprise and, where appropriate, supporting advanced analytical capabilities such as big data, artificial intelligence, and machine learning

- It builds sensors inside the enterprise to track performance, motivation and cultural health and acts on that data and information to continuously improve

- It focuses on purpose-driven business outcomes, not process: process exists to serve the result, not as a proxy for results

- Its people are organized within systems and assigned domains, often in cross-functional teams

- As skill requirements rise and fall, the enterprise becomes adept at matching efficiently to the right talent for every requirement and regularly redistributing workers to skill-relevant work

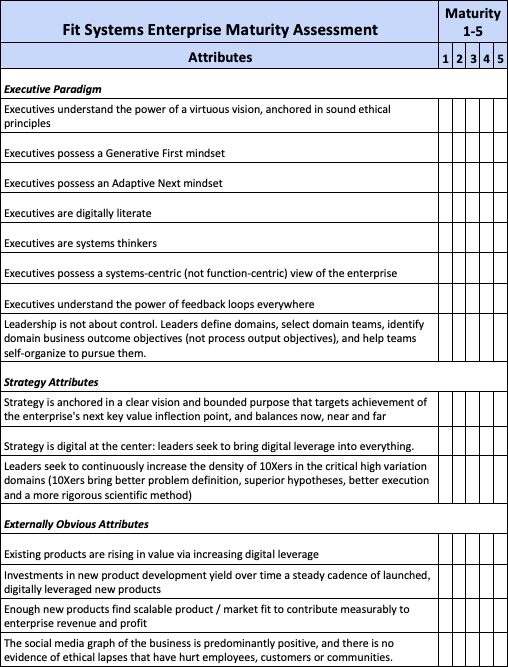

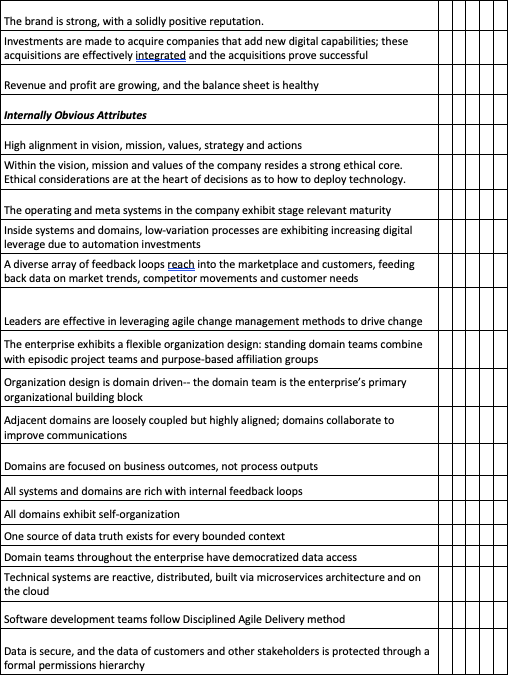

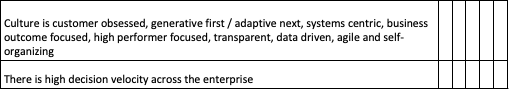

Take a moment to consider how your company stacks up:

If an enterprise isn’t fit, it’s flabby. The flabby systems enterprise isn’t generative. Its products lack digital leverage. Most of its leaders lack digital literacy. Scant attention is paid to the ethical issues associated with new technology. The enterprise boasts no recent product breakthroughs; revenues are excessively dependent on aging legacy products. These products are not being improved upon in a data-driven way. The flabby systems enterprise’s revenue engine remains functionally siloed, has a rigid and aging business model, lacks digital leverage and is sputtering. The enterprise is under threat from rising digital-first competitors.

Nor is the flabby systems enterprise adaptive. Its business processes are supported by aging technical vendor platforms. The pursuit of process efficiency has become an end in itself, costing enterprise resiliency and customer focus. Multiple sources of data truth obscure analysis. Loaded with technical debt, its monolithic technical systems are rigid and hard to modify. The pace of new software development is slow. The organization is structured as a set of functional silos. As ecosystem pressures rise, leaders find themselves stuck in silos, incapable of mobilizing an effective response. Competitors eat their lunch because they’re more efficient, can respond more effectively and can deliver better customer value.

What attributes must be included in this new paradigm? It must address:

- The significance of the generative imperative to survival and success

- The degree of outside-in orientation required to sense change and react

- The impact of rapid change on how decisions are made

- The impact of systems-centric enterprise design on enterprise resilience

- The imperative of digital literacy at the top

- The significance of well built, modular, modifiable digital technology

- The importance of thinking through the ethical issues associated with new technologies

- The extent to which agile methods and self-organized teams are key to building great digital technology

- The importance of data to decision making, and what that requires in sensors and infrastructure

- Which organizational forms are most capable of dealing with rapid change

- The implications on culture

- The requisite competencies of leadership

The Loop Paradigm

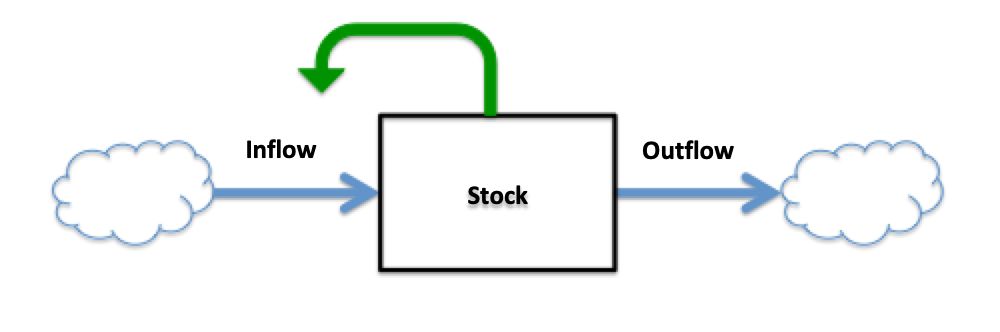

The digital era’s new leadership paradigm is called The Loop. A leader must guide the enterprise through digital disruption towards its generative and adaptive imperatives. The new leadership paradigm solves for survival and growth in the face of digital change. It applies to every stage of company, from startup to global enterprise. It depends upon a simple but powerful device: the feedback loop.

Feedback loops deliver flows critical information about current state. As a result they influence behavior, creating cause-and-effect cycles in systems. That’s why this paradigm is called “The Loop.”

In-The-Loop leaders are systems thinkers. They view the enterprise as a system living in an ecosystem, made up of subsystems, which in turn are made up of domains. Some domains are cross-functional, some are uni-functional. Some exhibit low variation in the nature of the work, some exhibit high variation. High variation domains are where change hits hardest, and where top talent is most important. The system-centric construct of the enterprise is the answer to the problem of functional silos.

Systems thinkers see the integrated nature of things. They understand that cause and effect are often separated in time and space. They know that change is the only constant. Ecosystem pressure points will rise, fall and shift. In-The-Loop leaders implement an array of outside-in sensors and feedback loops to keep track of these movements in the ecosystem. They also establish diverse feedback loops within the enterprise. These streams of data provide them insight into the current state, enabling them to set smart direction.

In-The-Loop leaders know that the first priority of the enterprise is to be generative. Customer value has a half-life, and must be replenished. The winning enterprise discovers evolving needs quickly and accurately. It iterates towards new product breakthroughs faster. It embeds digital leverage in its products. It leverages data to continuously improve its products.

They know the second priority is to be adaptive; in a fast-changing world, only a resilient, scalable and efficient company can shape-shift as required to keep pace with the ecosystem.

In the enterprise, systems are socio-technical. Technology doesn’t exist separate from everything else. Digital technology is deeply integrative: it is an extension of the human brain, and commingles with human action.

The In-The-Loop leader is digitally literate. She knows that to advance the purpose of the enterprise, its people, workflows, technology and money flows must interact together in an orchestrated way.

As such, all top executives (not just the heads of Product and Engineering) need to be technically fluent — to possess digital literacy. Only then can leaders support what it takes to build technology well and to gain digital leverage. These leaders will push to advance digital leverage in both products and processes. They will look to take advantage of new capabilities as they emerge (such as cloud computing, big data, machine learning, AI, Internet of Things, blockchain and so forth), whenever they add significant value. They will leverage new technologies consistent with ethical principles, ensuring that the interests and rights of all stakeholders are taken into account.

Conceived and built well, digital technology can deliver transformational leverage to a company. But when it is built poorly and fraught with technical debt, or outdated and difficult to modify, or (in the case of vendor tools) poorly chosen and implemented, it can drag a company down to its knees. It’s the lag that is the problem. There is a big lag between technology decisions and technology outcomes. Technology investments are large in money, time and people. Once bad outcomes have emerged from badly conceived or poorly built technology, it can take years to fix. Such consequences demoralize. The time spent fixing flawed technology is sucked away from growth initiatives. Meanwhile, fleet-of-foot competitors shoot ahead, powered by technology done well. This is why it’s so very important for a company to get its technology right. Wrong is deadly.

In-The-Loop leaders understand the importance of aligning roles and staffing with system purpose. Role by role, competency is necessary but not sufficient. They also pay attention to the motivation and energy of every person in the enterprise, through employee feedback loops.

In-The-Loop leaders understand the power of self-organization in systems. When change is constant, self-organization is a critical success factor. To achieve self-organization, they carefully select the domains inside each system that need dedicated teams. Where appropriate, they build cross-functional teams, giving them the autonomy to pursue a defined business outcome.

As leaders prioritize their actions and investments, they find the proper balance between now, near and far. They recognize that lags exist between an investment or an action and its outcome, and plan accordingly. When they act, they keep on the lookout for unintended effects — the system traps (archetypes) that can create dysfunctions or limitations to growth. They prefer to make a steady drumbeat of incremental improvements wherever possible, and to act in an agile way. But they will rip out any process that has outlived its usefulness. It’s the result, not the process, that matters. They are data driven. They work to achieve alignment and to increase the resiliency of the operating systems.

Here is a comparison of the four paradigms:

The world has changed. We are deep into the digital era, where waves of disruption crash hard and fast upon the enterprise. Only a digital-at-the-center, fit systems enterprise can survive and thrive in such a world.

It takes In The Loop leaders to build and grow such an enterprise.

. . .

Notes

- Albanese, Jason. “These 4 Companies Have Been Saved by Digital Transformation.” 2019. Inc.com. https://www.inc.com/jason-albanese/these-4-companies-have-been-saved-by-digital-transformation.html

- Deming, Edward. 1982. Productivity and Competitive Position.

- “Structural Functionalism”. 2019. En.Wikipedia.Org. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Structural_functionalism.

- Porter, Michael E. 1985. Competitive Advantage. New York: The Free Press.

- Peters, Tom, and Robert H Waterman. 1982. In Search Of Excellence. Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harper & Row.

- Grove, Andy. 1983. High Output Management.

- Katzenbach, Jon R, and Douglas K Smith. 1992. The Wisdom Of Teams: Creating The High-Performance Organization. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press.

- Hammer, M. and Champy, J. 2003. Reengineering the corporation. London: Nicholas Brearley.

- Collins, Jim, and Jerry I Porras. 2005. Built To Last. London: Random House Business Books.

- Treacy, Michael, and Frederik D Wiersema. 2007. The Discipline Of Market Leaders. New York: Basic Books.

. . .

To view all chapters go here.

If you would like more CEO insights into scaling your revenue engine and building a high-growth tech company, please visit us at CEOQuest.com, and follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter, and YouTube.