There are many ways to breach trust. You can fail to be transparent about how the consumer data you possess is monetized. You can fail to properly balance free speech with community protections. You can introduce algorithmic bias into consumer e-commerce transactions (such as lending). You can improperly tip the scales for some marketplace participants over others. Or you can breach trust by exposing your customers’ data to hackers. If you wanted to destroy enterprise value, it would be hard to find a better way to do it than to breach trust.

When you consider the magnitude of the risk, it’s shocking that stakeholder trust isn’t taken more seriously by leaders. Whether it be insufficient attention to security, or a failure of leaders to think through stakeholder rights and privileges, the failure is both ethical and technical. A breach of trust is proof positive that leaders didn’t care enough (or know enough) to protect it.

Facebook is a compelling object lesson. In 2018 the company suffered multiple hits to its brand, all related to trust. First came the Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which the data of millions of consumers was sold to a third party without user consent — exposing to the world that such non-consensual sales of private consumer data to third parties were commonplace. Then came the surge in complaints about Facebook’s loose community content standards, as demonstrated in rising incidences of misinformation, hate speech and spam. Next up, the company announced a security breach in which the data of thirty million users was exposed. Then news emerged that the company had worked with a PR firm to attack its rivals in the news while pushing positive Facebook stories. The cumulative effect on the stock price was dramatic. In 2018, the price fell 36% from its July high of $207 to $133 by the end of year.

Target, Equifax, JP Morgan, Nike, Orbitz, T-Mobile and many more have experienced security breaches (the most basic type of trust breach) and have suffered the consequences. A recent study showed that the stock prices of public companies which have experienced a data breach have underperformed the NASDAQ by an average of 42% in the three years subsequent to the breach¹.

Is your company trustworthy? If so it is because you and other leaders have made it that way. In the fit systems enterprise, trust is systemic. It is built into your brand and codified in your culture. You have architected trust into all your systems — across people, workflows, technology and money flows. You have done so on behalf of all stakeholders — your customers, community, partners, vendors, investors and employees.

As with Maslow’s hierarchy, trust begins at the bottom with enterprise security: safety. But stakeholder rights and privileges extend well beyond that. Some are universal; others emerge from business model and product strategy. It’s on enterprise leaders to design these rights and privileges into systems. The factors you must weigh bear both ethical and technical implications. Six topics related to trust merit attention:

- Building trust into the business model and platform design

- Sustaining stakeholder trust

- Permissions and data governance

- Safety and enterprise security

- Trust and blockchain

- Trust and artificial intelligence

Building Trust into the Business Model and Platform Design

It all starts with you, the leader. Across all business models, trust tends to come down to five things: authenticity, fair intent, reciprocity, proof of expertise and safety. Are you who you say you are? Are your intentions honorable? Is there a fair balance between risk and reward, between my interests and the interests of counterparties, and between what I invest and what I receive in return? Can I have confidence in the quality of your platform and the expertise of its participants? Can I have confidence that my data will be protected, and that your platform will remain up and available at all times?

You can’t build these attributes into your business model and platform if you yourself are not ethically grounded. Lacking an ethical frame, you won’t have the mindset to do it well. The ethical leader brings six virtues to the task of forming a business model and building a platform. These will look familiar. They can be found in the roots of human philosophy, as expressed in both Eastern and Western ethical traditions:

- Temperance (to balance your self-interest with the interests of all stakeholders)

- Prudence (to balance risk and reward for yourself and others)

- Courage (to defend the interests of all stakeholders against the temptations of self-interest or attacks from others)

- Justice (to ensure due process protections for all stakeholders)

- Caring (to tune into and act on the needs and interests of all stakeholders)

- Quality (to ensure trustworthiness in platform design, content and technical systems)

Trust architecture is anchored in basic human virtue.

For instance, if yours is a media company, the source of your content is clearly defined to the reader. Editorial content is objective and written independent of economic influence. Advertiser influenced content is designated accordingly (usually called “Sponsored Content”). User generated content is shared consistent with defined and published community standards. You exercise great care in protecting different groups of users — such as minorities from hate speech, children from inappropriate content and citizens from algorithmic polarization. You design into your systems the people (such as moderators), workflows (such as content publishing workflows) and technology (such as AI-based compliance scans of user generated content) to accomplish these ethical objectives.

If yours is a B2B marketplace, payments are secure. The “rake” (the percentage your company takes from each transaction) is clearly identified to all parties. If larger participants receive better economic terms, these differences are clear to all. Buyers and sellers can and do evaluate each other, creating star ratings and reviews that are hard to “game” and are not algorithmically biased. Counterparties are clear about the rules of engagement; these are followed without exception. There is due process for dispute resolution.

If yours is a B2C SaaS platform, the purchase experience is easy but not deceptive. If the annual subscription auto-renews, this is clearly stated in initial purchase terms. Cancellation is straightforward. The consumer can easily opt out of email marketing.

Whether your business model is e-commerce (returns), or gaming (addiction), or Yelp-like ratings site (algorithmic bias), each has its own unique trust considerations. The choices are often difficult. You’ll find yourself dealing with issues that look a lot like public policy. Personal freedom versus protection of minorities. Centralized policing versus community policing. The balance of powers. Taxes and the sharing of rewards. Due process. Sounds like government, right? Well, in a sense it is. Your platform is a socio-technical system that brings together many stakeholders. It must be governed by rules. The rules you set must balance the needs of all. These rules are the foundation of trust. You must build them into platform design, and then maintain and improve them based on feedback from your platform’s citizens. Just like government.

Take the time to conduct a trust audit. Start with your stakeholders. Depending on your business model, you may serve one or more type of customer. Perhaps your platform touches both businesses and consumers, as with AirBnB. Perhaps you have important partner and vendor relationships. Your impact on the community may or may not be significant. You most definitely need to consider investors and employees. As you consider each stakeholder, consider the following:

- Your company’s own economic position inside your platform

- How the rules of the game affect each stakeholder

- What transparency agreements you have made

- What privacy agreements you have made

- What data property rights you offer

- What degree of compliance management you offer

- What due process you offer

- Where might you risk algorithmic bias

As you conduct this review, is any one stakeholder unfairly treated? Have you built into your business model and platform authenticity, fair intent, reciprocity, proof of expertise and safety? This isn’t a project. The work to build trust into your business model and platform design is a journey that never ends.

Sustaining Stakeholder Trust

While it’s very important to architect trust into your business model and platform design, it’s not enough. You have to sustain that trust, on behalf of all stakeholders. This includes:

- Continuity between what you say and what you do (no misrepresentations of product value; no violating your own rules; no changing of the goal posts)

- Fair play when interests diverge (balancing of stakeholder interests in issue resolution)

- Due process (a method for resolving conflicts between parties)

- Bad news transparency (such as updating customers when the platform goes down; providing immediate alerts in the event of a data breach; updating investors when there is a material adverse change)

- Reparations when damage has been done (such as crediting a customer bill)

Different stakeholders care about different types of issues.

Customers

Customers expect to receive promised value from your platform. The claims made by a salesperson and your customer’s post-purchase product experience need to be in alignment. Customers also expect their profile and status to be private, and their data to be secure. They expect the rules of the game to be clear and followed. When something goes wrong, they expect to be alerted and for wrongs to be righted.

The more these expectations can be built into the platform itself, the better. Where humans are the means of assurance, competency, staffing levels and workflows need to be up to the task.

Community

Depending on your product and business model, your company may impact the broader community. Facebook has changed the tone of political engagement. Twitter has contributed to the rise of online mobs and public shamings. Google’s search algorithms impact the survival of small businesses, AirBnB impacts city zoning laws, Lyft and Uberimpact public and licensed transportation in cities, and Amazon’s Alexa puts a listening device into private homes. There are complex ethical issues underlying these community effects. In the fit systems enterprise, In The Loop leaders ponder community impact in their product and business model design.

Partners

Partners are integrated into your product itself, or are channels of distribution. In the course of executing their roles, they may expose their private data and methods to you. Partners expect you to protect their proprietary information. They expect technical fidelity in integration and data passing. When technical systems fail, they expect to be in the information loop and to be a full partner in issue resolution.

Investors

Investors expect you to alert them as to any material adverse change. Bad news transparency is a hallmark of a trusting investor relationship. In public companies, information about company performance must be released to the public consistent with SEC regulations so as to insure all investors, large and small, have the same timely access to the information.

Employees

HR employees, programmers, finance employees, lawyers and data scientists have access to and must exercise care with confidential data. Customer success representatives can access customer profile and status data, and are key agents of issue resolution. Managers and executives are insiders bearing substantive knowledge of company performance that, especially in a public company, must be protected. Employees are critical actors in the maintenance of trust.

But employees themselves also expect to work in a trustworthy environment. In Chapter 17 I reviewed the importance of the Culture System in maintaining employee trust. Employees need to know the degree of privacy they can expect in communications systems, such as company email systems. Are all employee emails reviewable by management? If so, employees should know that. Any HR department is in possession of highly sensitive personal data about individual employees. Clear cultural values, transparent communications, a commitment to employee development, employee due process and maintenance of bottoms-up feedback systems are all pieces of the trust puzzle.

Technical steps are required to protect confidentiality. Technical systems must be built securely, and the people who can touch these systems sworn to confidentiality.

Permissions and Data Governance

One of the most important questions to address in trust architecture is permissions. Who should be able to access what data? As the amount of data a company can gather grows, much of it personal or private, this question looms ever larger. Data scientists training AI and ML datasets will have access to highly confidential data not available to other employees. Senior executives will have access to company performance data that may not be available to frontline employees.

The protection of the information rights of stakeholders necessitates a permissions hierarchy. It is one of the most important components of an effective trust architecture. But this hierarchy fights against the principle of democratized data access. In the fit systems enterprise, there is an ongoing tension between the need for data control and the need for data freedom. To be in the loop, leaders need data. Domain teams need data to continuously improve. How can these conflicting needs be resolved?

The answer is anchored in ethical principles. Stakeholder interests must be protected, and the rules of protection must be clear. Personalized, confidential data must be made accessible only those who must have access to it to do the job all stakeholders want done. Employees with access to such data must be bound by iron clad confidentiality agreements. Customers and other stakeholders must be informed in privacy statements as to who has access to their data. Any data made available to domain teams and management must, wherever possible, be anonymized. As to company performance data, the executive team needs to determine who will have access, and make sure these permissions are built into management information systems.

As covered in Chapter 16, the rules that guide the dissemination of data throughout the enterprise are the responsibility of the DataOps system to devise and manage. In the larger enterprise, a DataOps council will wrestle with issues of data privacy vs. data access. When necessary, they will bring the most vexing questions to the executive team (or even the CEO) for resolution.

Safety and Enterprise Security

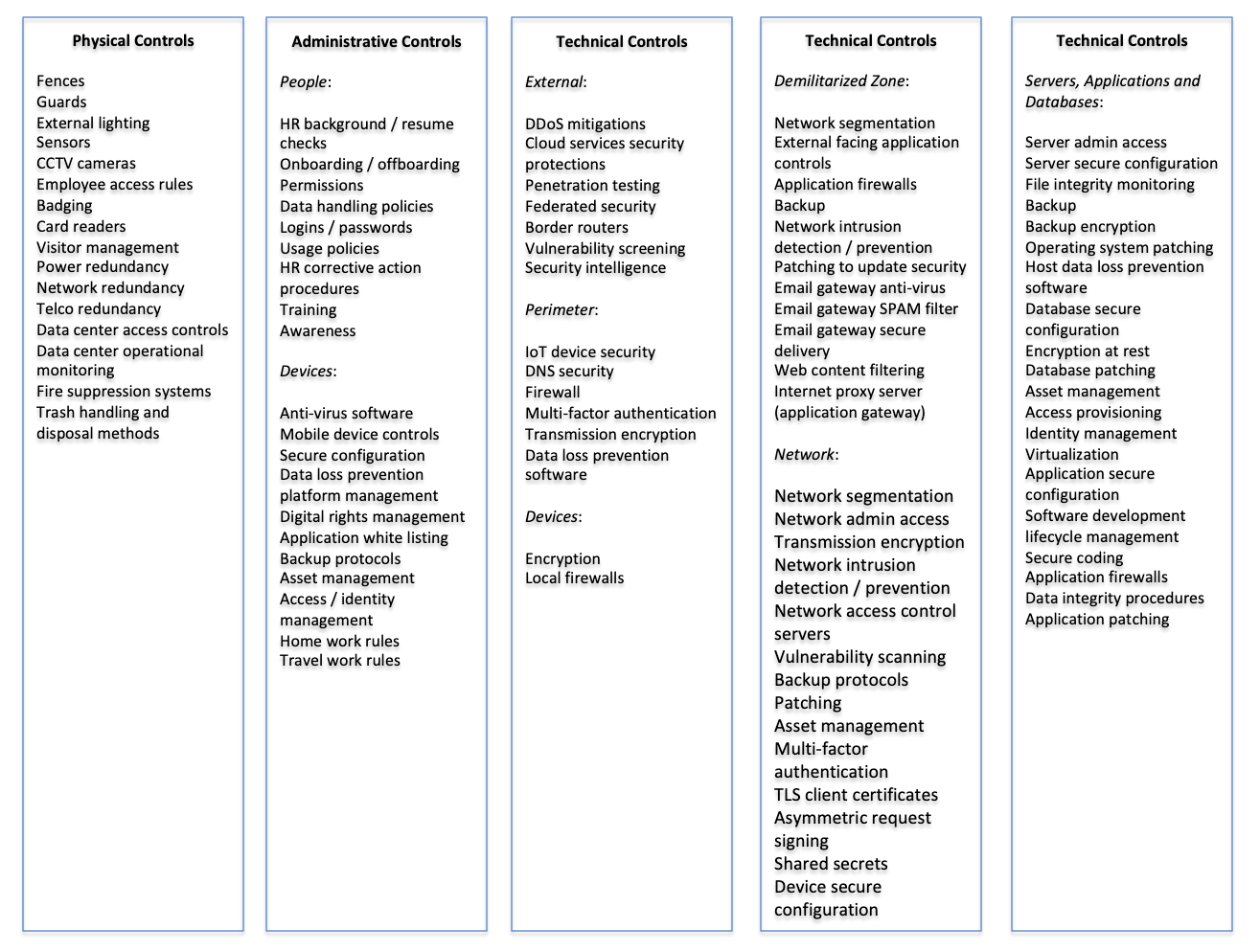

To ensure that data access follows the permissions hierarchy and that underlying technical systems are protected from harm, a series of controls must be put into place. These controls are both technical and human. If you’re an In The Loop leader, you will respect the critical importance of enterprise security in protecting the safety of all stakeholders. You will give your technical leaders and teams the resources they need to build and maintain the proper physical, administrative and technical controls throughout the enterprise.

Best practice enterprise security follows a “zero trust” model: the systems design assumption is that any actor within or outside the company could be a bad actor. It also assumes “Murphy’s Law”: anything that can go wrong will go wrong. Enterprise security protects from both deliberate attack and threats to business continuity.

Physical Controls

It starts with physical controls. The sophistication of these controls will be guided by the company’s stage and the degree of impact of a breach. A nuclear plant will have more extensive security than a social media platform company. In the fit systems enterprise, when the security threshold needs to be high physical controls are audited, with physical penetration tests to discover vulnerabilities.

Administrative Controls

Administrative controls are the human workflows and procedures that support enterprise security.

Technical Controls

Technical controls are built to provide defense in depth. Security is layered, confronting threats in the external ecosystem; the perimeter; the demilitarized zone; the network; in workstations, laptops, smartphones and BYOD; and in servers, applications and databases.

The following graphic lists detailed considerations in the areas of physical, administrative and technical controls:

Trust and Blockchain

Blockchain is part of trust architecture for a growing list of companies. Its relevance goes well beyond Bitcoin. Blockchain makes it harder for digital data to be misused, and as such is relevant in a variety of use cases. Companies who must share data with external parties should assess whether blockchain can strengthen trust architecture. The essential benefit of blockchain is data integrity. Since any data file runs the risk of being copied and exposed to others, it also runs the risk of becoming corrupted. Blockchain prevents that.

Blockchain places data within a strict rules framework. Only people with the right digital keys can add to the data in the blockchain. The data may be visible on the web, but it can’t be altered in any way without proper permission — the digital key. The rules are enforced via crowdsourcing — many users maintain stability of the system, ensuring no need for a central bank. Bitcoin uses blockchain because it prevents counterfeiting. Any company can use blockchain to make the sharing of data with external parties (partners and even competitors) safe. Insurers use blockchain to securely share personal health data, such as with health care providers. Use of blockchain is rapidly expanding as companies discover new scenarios in which the technology can improve security. From supply chain management to asset tracking to payments, blockchain is changing trust architecture. Some have even envisioned a day when blockchain will enable secure online voting.

Trust and Artificial Intelligence

The rise of artificial intelligence brings with it ethical issues. When a machine can determine who gets a job or a loan, or who reads what, or where the smartbomb will land, or whether it will be the grandma or the child who is run over by a careening autonomous vehicle, stakeholders will understandably question the trustworthiness of AI.

This is especially the case with deep learning, where the logic underlying an automated, cognitive action is opaque. By its nature, deep learning computations involve so many layers of analysis it becomes very difficult to define the logic behind its output.

When AI is used by a platform to decide how stakeholders will be treated, one would think that the ethical thing to do would be to make clear to the affected person the logic of the system’s governance decisions. But it may not be that easy. Will Knight, in an article, “The Deep Secret at the Heart of AI” says it this way:

There’s already an argument that being able to interrogate an AI system about how it reached its conclusions is a fundamental legal right. Starting in the summer of 2018, the European Union may require that companies be able to give users an explanation for decisions that automated systems reach. This might be impossible, even for systems that seem relatively simple on the surface, such as the apps and websites that use deep learning to serve ads or recommend songs. The computers that run those services have programmed themselves, and they have done it in ways we cannot understand. Even the engineers who build these apps cannot fully explain their behavior…

This raises mind-boggling questions. As the technology advances, we might soon cross some threshold beyond which using AI requires a leap of faith. Sure, we humans can’t always truly explain our thought processes either — but we find ways to intuitively trust and gauge people. Will that also be possible with machines that think and make decisions differently from the way a human would? We’ve never before built machines that operate in ways their creators don’t understand. How well can we expect to communicate — and get along with — intelligent machines that could be unpredictable and inscrutable²?

Only an In The Loop leader can effectively engage issues such as these, with their many layers of ethical complexity. In the end, it’s all about earning trust. AI datasets are trained by data scientists. The problems they seek to solve and the training they apply emerge from an ethical frame. In the fit systems enterprise, In The Loop leaders work hard to ensure its data scientists and architects are diverse, ethically grounded, and bring the interests of all stakeholders into the center of technical design.

Summary

It is fitting that trust is the subject of the final chapter of this book. In the fit systems enterprise, trust is central. You can’t create customer value (the generative imperative) without trust. You can’t attract investors and scale (the adaptive imperative) without trust. In the absence of trust, your operating and meta systems are rendered impotent.

It might seem out of place for a chapter on trust to be included in the “Digital Literacy” section of the book. But that’s intentional. It’s important for both technical and non-technical leaders to appreciate the degree to which technology and ethics are interwoven. In capable hands, today’s powerful technologies can work wonders. But that begs the imperative that they be used for good. In the wrong hands, technology is a dark art capable of inflicting great harm. “Goodness” is elusive. It can only be discovered in the ethical resolution of a continuous stream of decisions — large and small, technical and non-technical, executive-level and domain team-level — made throughout the enterprise every day.

This complicated, messy search for goodness can only be conducted well by leaders who are ethically grounded, digitally literate systems thinkers. That’s the only way. To build a fit systems enterprise, leaders must be In The Loop. Only then can you build trust with customers and other stakeholders.

And in the end, it’s all about trust.

To view all chapters go here.

If you would like more CEO insights into scaling your revenue engine and building a high-growth tech company, please visit us at CEOQuest.com, and follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter, and YouTube.

Notes

- O’Connell, Brian. “Companies That Suffer a Data Breach See 42% Slide in Stock Price.” TheStreet, July 12, 2017. https://www.thestreet.com/story/14224071/1/companies-that-suffer-a-data-breach-see-42-slide-in-stock-price.html.

- Knight, Will. “There’s a Big Problem with AI: Even Its Creators Can’t Explain How It Works.” MIT Technology Review. MIT Technology Review, May 12, 2017. https://www.technologyreview.com/s/604087/the-dark-secret-at-the-heart-of-ai/.