If you are a senior executive of a fast-rising startup, this chapter is not for you. It is written for the leader of a large enterprise — one that is at risk due to rising competitors and digital disadvantage.

Let’s say you are the new CEO of stalled-out legacy enterprise with a post-peak product line. The previous CEO cut costs to the bone, boosting profits for a few quarters. But that play has run its course. Revenue has begun to decline. The value advantage your company held for years is now challenged. Digital-at-the-center upstarts have leveraged modern technology to deliver a superior product while simultaneously undercutting you on price.

Worse, you don’t have the data you need to run your business. And it’s taking way too long to fix the problem. Your monolithic legacy technology infrastructure is brittle, making it hard to update. Your technical team has the skills to maintain the monolith, but can’t upgrade it without weeks and months of planning. And they don’t possess the skills to build modern technical systems. Your organization is siloed, the culture stodgy. You’re caught in a trap, and you need to get out. What do you do?

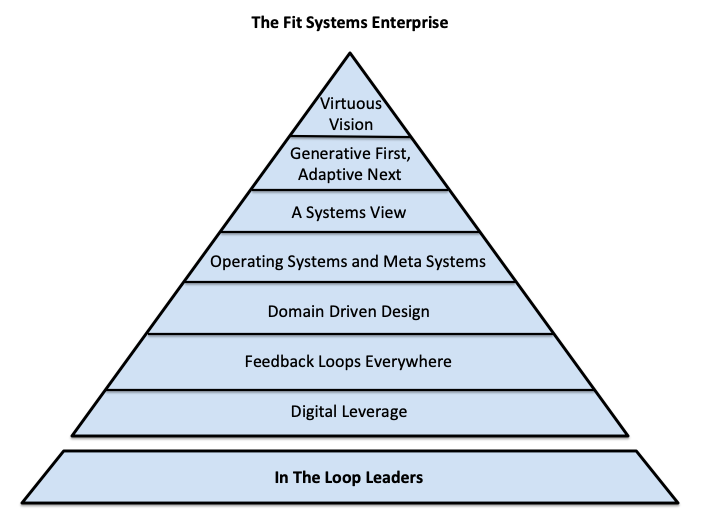

Because you are an In The Loop leader, you know the end in mind. You need to become a fit systems enterprise: a digital-at-the-center company capable of continuously advancing its generative and adaptive imperatives on the road to ecosystem leadership. You know the characteristics of a fit systems enterprise:

But how do you build these characteristics into your company?

It requires two multi-year transformations. First, you need a generative transformation. You need to rediscover your generative DNA, so you can rebuild the value advantage you once enjoyed. Second, you need a digital transformation. You need to transform your technical systems into cloud-based, reactive microservices capable of leveraging advanced technologies, supported by a data infrastructure capable of democratizing data access throughout your company. Only through these two transformations will your products and processes fulfill your generative and adaptive imperatives.

The chapter is organized into four parts:

- The attributes of the at-risk enterprise

- Generative transformation: end in mind

- Digital transformation: end in mind

- Mobilizing the enterprise

Attributes of the At-Risk Enterprise

An enterprise is most at risk when it has lost its generativeness. This happens when its connection to customers and their needs weakens — often seen in a lack of digital product leverage relative to competitors. In the at-risk enterprise, new product initiatives are stalled. Optimizations of existing products haven’t meaningfully improved customer value. The product line is mature and relative product value is in decline.

In such an enterprise, leaders blow hot air into legacy products but don’t pay enough attention to new product development. Because business units are incented to protect and grow their existing products, any new product initiative that might disrupt existing product value is suppressed. Only “safe” initiatives that don’t threaten the core are tolerated.

When a rogue new product initiative sneaks through and begins to show promise, it runs aground. The team that developed it doesn’t receive the support to scale it. As the nascent product enters the existing sales structure, a buzzsaw of conflicting priorities cuts it down. Enterprise salespeople have no interest in selling a “side” product that yields small commission checks when they get a much bigger check for selling the legacy product. Executives aren’t motivated either, for the same reason. The incentive system gets in the way. And when new product concepts don’t fit neatly into the preexisting business unit structure, opportunity ducks out the door as executives debate how to divide the spoils.

Decisions are slow and bureaucratic. The building blocks of self-organization and small-group decision making are not in place, so every non-standard business problem needs to flow up the totem pole for resolution. Functional executives work hard to protect their fiefdoms, impeding holistic solutions.

Because of its post-peak products, revenue growth has slowed or reversed. For the public company, this means the investor mix is dominated by value investors impatient for change. They press for radical cost reduction, or an enterprise breakup, or other financial engineering maneuvers to drive short term profit growth or return capital to investors. They have no appetite for a multi-year generative or digital transformation. Pressure rises on the company’s board to take action.

Since top executives have have followed the cost-cutting playbook for years, aging products have been milked dry. Seeking savings, they have re-engineered internal processes to the point they have become rigid and brittle. Functional silos execute formal function-to-function handoffs within low-variation processes. What is done is done efficiently, but when “what must be done” needs to change, the organization can’t easily execute. Like its technical systems, the company’s organization is monolithic and brittle.

Functional leaders exercise control and expect workers to execute standard operating procedure. Workers can provide feedback, but the focus is on continuous process improvement of existing processes. The process is the thing.

Monolithic technical systems are mostly maintained on premises. Due to a complex web of tightly coupled interdependencies, they can’t be easily updated. Technical teams are well aware of agile methods, but can’t pursue them because the existing technology won’t allow it. There is a history of system failures caused by faulty updates. As a result, the Operations team is risk averse and acts as an intentional bottleneck to restrict updates. Every update must progress through a waterfall development approach so dependencies can be thought through up front. A handful of senior engineers are the “keepers of all knowledge”, the only ones with enough experience to know the dependencies and fix the monolith when someone breaks it.

Some cloud-based side projects might be underway, but these remain at the edges. The technical teams responsible for these initiatives fight to self-organize and pursue agile methods, but the culture fights back. Technical leaders don’t understand or support the idea of self-organization. The IT culture values software outputs over business outcomes. Engineers are measured on code production per week, not on their contribution towards achieving business outcome objectives.

The enterprise’s technical executives don’t know how to mobilize a monolith migration. They fear they will screw everything up. This lack of a mental model for change undermines courage. Leaders find more job security in managing the monolith than in accelerating the journey to break it down.

With opportunities and jobs shrinking due to cost cuts, a scarcity mentality takes over. Executives scheme to protect spans of control. Failures are penalized. A blame-based culture emerges. External recruiters catch wind of trouble and press their attack, picking off the best talent. Top performers move on to greener pastures, while weaker performers remain. Lacking a narrative that could attract new blood, the enterprise’s stock of human competency declines.

As fleet-of-foot competitors rise, the at-risk enterprise stumbles towards the cliff — slow, rigid, brittle, internally focused and digitally challenged.

Generative Transformation: End in Mind

To transform, the enterprise must begin at the beginning: by rediscovering its generative DNA.

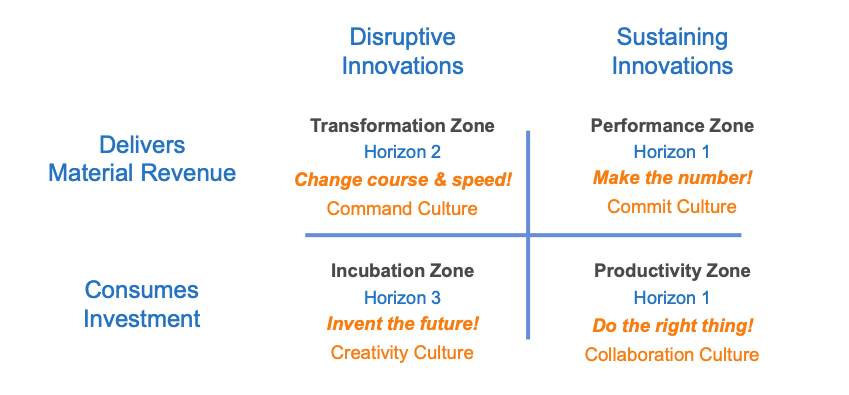

In Zone to Win¹, Geoffrey Moore puts forward a generative transformation framework. He posits that enterprises must adopt three investment horizons: horizon one, with an ROI in 0 to 12 months (current product and process improvements); horizon two, with ROI in 12 to 36 months (fast scaling new products); and horizon three, with ROI in 36 to 72 months (new product experiments).

Investments in each of these horizons must drive two types of innovations — sustaining and disruptive. Sustaining innovations are backward-compatible — meaning they are incremental improvements to current products that don’t require a change in buyer and user behavior. Disruptive innovations require more fundamental change to buyer and user behavior, but deliver significant new breakthroughs. Disruptive product innovations are the ones most likely to leverage emerging technologies, such as Internet of Things, mobile, social, big data, machine learning and AI.

Horizon three investments are risky. These investments look a lot like early stage startups. You need to approach them like a VC would — invest in the idea and the team, and keep investments small until you see signal of product / market fit. Each next investment should be based on achieving a value inflection point. Large enterprises engage in horizon three investments by launching enterprise incubators, funding skunkworks projects, and making early stage corporate venture investments.

Moore argues that the three horizons are pursued differently at different times, based on the prevailing competitive dynamics:

SOURCE: Moore, Geoffrey. Zone to Win: Organizing to Compete in an Age of Disruption. Diversion Books, 2015.

When the enterprise is being hit by a wave of disruption, it must play zone defense: its first priority is the transformation zone; second is the incubation zone and the performance zone is third. When the enterprise is riding a wave, it can shift gears: transformation zone first, performance zone second and productivity zone third. In between waves, it can focus first on the performance zone, second on the productivity zone and third on the incubation zone. Each zone requires a different culture, which is why it’s so important to prioritize.

Moore’s framework aligns with In The Loop thinking. In the fit systems enterprise, the product discovery system exists to pursue (using Moore’s word) disruptive innovations. Product discovery system teams immerse in the marketplace, conceive of new innovation hypotheses, redefine the business model, build new products, find product / market fit and create new streams of value. Product discovery team investments are “horizon three” investments. Teams inside the product management system pursue sustaining innovations — improvements to existing products and services. These can be “horizon one” or “horizon two” investments. As Moore indicated, the weighting of these investments will depend on the enterprise’s current competitive position in its ecosystem.

Digital Transformation: End in Mind

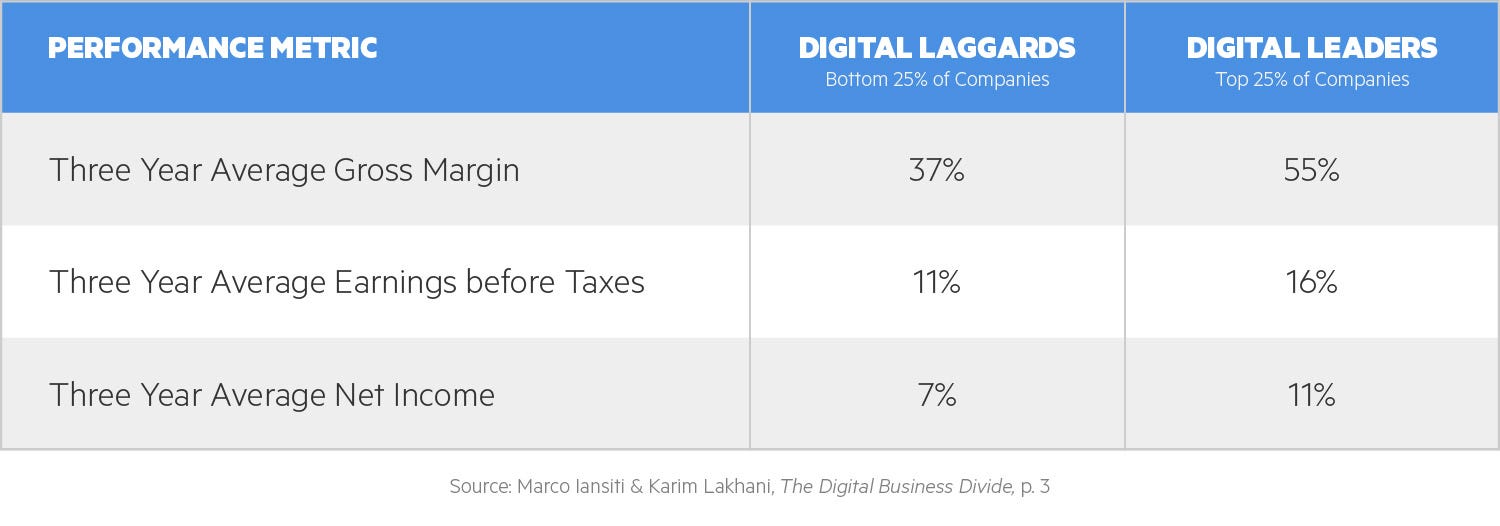

Digital transformation enables advancement of the generative imperative (build innovative digital products) and adaptive imperative (build new feedback loops and automate processes). CEOs who commit to digital transformation do so to gain digital leverage. That’s why Tien Tzuo at Zuora and Kevin Johnson at Starbucks have spent years driving transformation agendas at their respective companies. The upside is huge.

In fact, a Harvard Business School study² shows that digital leaders exhibit substantially higher performance than digital laggards. Authors Robert Bock, Marco Iansiti and Karim Lakhani studied large companies and enterprises (>$3.4B) in the Consumer Packaged Goods, Financial Services, Manufacturing and Retail Industries. They found a digital divide between leaders and laggards, as shown below:

SOURCE: Harvard Business Review, “What The Companies on the Right Side of the Digital Divide Have In Common”, by Robert Bock, Marco Iansiti and Karim Lakhani, January 31, 2017

Clearly, digital advantage rewards the bottom line. But the downside of failing to transform is also a powerful motivator. In a 2018 McKinsey study, only eight percent of companies reported that their current business model would remain viable if their industry keeps digitizing at the current course and speed³.

That’s why everyone’s pursuing digital transformation. In a 2019 survey of IT professionals by Dimensional Research, 100% of respondents indicated their teams are in the midst of technology modernization initiatives. The reasons include cost reduction (79%), customer satisfaction (68%), employee efficiency and satisfaction (59%), to drive revenue growth (55%), to enter new markets (43%), to respond to competitive pressure (42%) and to grow their positions in existing markets (42%)⁴.

At the heart of digital transformation is the monolith overhaul. It’s not easy. By definition, a monolith is comprised of components that are tightly coupled with each other. The worst monoliths are like huge plates of spaghetti — with all kinds of tightly coupled dependencies intertwined. For older global companies, the monolith might be made up of 10,000 engineer-years or more of code. But you have no choice. Your ecosystem won’t stay still just because your monolith is hard to refactor. It’s time to get on with it.

Risks

It’s easy to do it wrong. In fact, a McKinsey study from 2013 reported a failure rate of 70%⁵. Another study by KPMG found that less than half of executives at companies in the midst of digital transformations believe they will be successful.

The Dimensional Research study found that 99% of IT professionals face challenges with technology modernization. 56% are struggling to balance cost management and system performance. 46% reported struggling to build flexible cloud-based (microservices) architectures. 46% reported they were under pressure to build solutions faster. 43% reported problems finding people who had the right technical skills, and 38% said they lacked the necessary skills in modernization strategies. 41% were having issues with scaling complex systems, and 39% reported issues with siloed data⁶.

Before you embark on your digital transformation journey, it is worth paying particular attention to six key risks. All of them come down to a failure to think systemically.

The first risk is to see digital transformation as a technology problem. It’s not — it’s a business problem. Some CEOs think that once they swap out the old technology with the new, they’re done. But a company’s existing technology lives inside its systems and domains. It is interwoven with people, workflows and money flows — often in complex ways.

The second risk is to build new technology around yesterday’s business strategy and business model. Strategy, business model and technical systems transformation all need to be thought through together. New technical capabilities shouldn’t just improve the solutions to yesterday’s problems. Leverage them to rethink the problems themselves. They will no doubt lead you to new opportunities and new technical road maps.

The third risk is that in attempting to define to the board and senior executives the costs, benefits and timeline of the transformation, you end up establishing a rigid contract against which your performance will be measured. The reality is that you can’t predict all of the obstacles and opportunities you will encounter. So any prediction of costs, benefits and timelines is at best a rough estimate. Frankly, costs are almost always higher and timelines longer than anyone expected. You can only hope that the benefits surpass expectations as well.

The fourth risk is that you fail to appreciate the degree to which digital transformation changes the power structure and culture of your company. If you don’t work hard enough to build business and technical team alignment, the people most threatened by the changes may work to undermine them.

The fifth risk is that you don’t adequately understand how your business runs today, and the role technology plays to support daily operations — resulting in unintended effects when you make technology changes.

The sixth risk is that the leaders and teams responsible for the transformation don’t adequately understand how to build the new technology capabilities and how to leverage modern architectural methods, resulting in new technical systems that are architected poorly, fall short of their promise or are hobbled by design flaws.

In digital transformation, the end in mind is a set of modern, modular, cloud-based technical systems that support innovative digital products (the generative imperative), and increase resiliency, scalability and efficiency (the adaptive imperative).

Mobilization

The journey to a generative, digital-at-the-center, fit systems enterprise is made in five stages:

- Stage 0: Preparation

- Stage 1: First Projects

- Stage 2: New Product Experimentation

- Stage 3: The Big Move

- Stage 4: Inversion

- Stage 5: Optimization

Stage 0: Preparation

In order to embark on a new strategic path, you first need to:

- Deepen your understanding of the problems

- Clarify your vision and mobilization path

- Come to terms with the time and cost required to achieve real change

- Build support at the top

Deepen Understanding of the Problem

You need to better define the current state of your generative muscle and digital systems. First, assess your generativeness. What’s the degree of risk you face from rising digital competitors? Are your products at a widening digital disadvantage?

When I was at the Star Tribune in the mid nineties, I was selected to join a team whose purpose it was to take stock of our market position and confront the rise of the Internet. At the time I was a director-level mid-manager. I joined other mid-managers on this twelve person strategy team. We met two days a week for six months, during which time we conducted research, talked with customers, evaluated data, looked at our culture, sought input from employees and engaged in a series of strategy debates. The team, led by the publisher-to-be, eventually developed a high level vision and strategy. We presented it to the entire executive team. After feedback and some adjustments, the top team acted on its key recommendations and rolled out a reorganization of the company. It was hard work, but two years later our customer satisfaction, revenue and profit had jumped significantly.

This small strategy team approach is an effective first step in strategy development. As CEO, it allows you to temporarily bypass your executive team, where entrenched resistance to change might lurk. Pull in five to ten of your rising stars — wicked smart, curious, ambitious director-level people with enough domain and company expertise to be relevant but not so much as to be wedded to current state. Then get out of the office and into your customer’s world. Conduct both analytical and experiential research. The latter is more powerful than the former, though both are important. Look for data in the market, but also track internal data. Consider rising technologies, and how they may apply to what you do. Study competitors. Study yourself — where are you most vulnerable? Then guide the team towards strategic implications and a high level vision and plan to rebuild generative muscle.

When this team shares its findings and recommendations with the executive team and upper mid management, you may encounter pushback. Perhaps your findings imply future changes to the organization. Some executives might challenge the recommendations. Issues and concerns raised by executives are important feedback loops. If they point to real obstacles or decision factors that need to be better understood, they will inform strategy and execution. It’s perfectly OK at this stage for the team to go back and iterate on the plan. But if the pushback reflects selfish entrenched interests, good to know. You now have pinpointed pockets of resistance, and can take this data into account as you move to the next stage.

Once this first strategic project has been completed, it may make sense to bring in a top echelon consulting firm, such as McKinsey or Bain to go deeper. This hired team can provide additional validation or refinement of the initial recommendations, enriched with market data and the external pattern recognition such top tier consulting firms can provide. The results of this work will help deepen understanding and — perhaps most important — address the obstacles raised by executives and managers the first time around. As the concerns of these executives are engaged and addressed, their mental models may evolve.

The second problem is to assess the current state of your technical systems. Technical infrastructure is critical to gaining digital product leverage. In its current state, it may well be a key limiting factor to the new product vision. So you need to understand what you’ve got, and what it will take to upgrade it. Once again, an external consultant such as Accenture (large firm), or Slalom (mid sized firm) might help you define current state with the necessary rigor. Consulting firms such as these have the people and methods to help you assess your current capabilities, and the limitations they might place on your product vision and process optimization potential.

Clarify Your Vision and Mobilization Path

These two preparatory steps should help you, the CEO, confront the reality of your product and technology gaps. With data and recommendations in hand, you will need to define the path forward. Three years after becoming CEO of General Motors, Mary Barra rolled out a new vision for the company: zero emissions, zero crashes and zero congestion. It has shaped the company’s path ever since. But it didn’t come out of nowhere. It emerged from a period of internal strategic engagement, introspection and experimentation.

A high level vision is, of course, just the starting point. You need to choose a mobilization path. There are six possible paths to advance a generative and digital transformation:

- No obvious changes to the existing product, but digitally optimize processes to strengthen the customer experience (Costco)

- Build digital leverage directly into the customer experience, while keeping the underlying product similar (DisneyWorld — for instance, the magic wand)

- Build new products with separate teams; transition the successful ones into business units that lightly leverage the legacy business (Lego — for instance, its homegrown product “Lego Boost” features an app-based simple coding tool children can use to guide movements of Lego creations)

- Acquire a successful digital-at-the-core business; let it operate adjacent to the legacy business and integrate slowly (General Motors — for instance, the Cruise Automation acquisition)

- Build a completely new and separate digital business, then integrate with the legacy business (Walmart.com)

- Rebuild the product into a digital-first business, and then let the old product die (Netflix)

Time and Cost

Once you clarify the high level mobilization path, you can begin reckoning with the cost and time it will take to execute the necessary change. As you factor in the time required, remember that behavior change is hard. How will each of your top executives react? Are they systems thinkers? Are they digitally literate? Do their incentives impact their point of view? Are they directly threatened by the changes you contemplate?

Executing transformation will require big multi-year investments — such as new product development initiatives and acquisitions (generative); and monolith migration (digital). Generative and digital transformations aren’t cheap. If you have engaged consulting firms in your transformation research, they will help you size these investments.

Build Support at the Top

You will need to build support at the executive level. Most of your executive team will be focused on running the business you already have, but you’ll need to build an inner circle of trusted top executives who share your vision to become a digital-at-the-center, fit systems enterprise. These In The Loop leaders will be your partners on the journey.

You also need to bring along your board. Are all board members digitally literate systems thinkers? Do they fully appreciate the risk of inaction? Have you helped your board understand the significance of the changes you must make, and the time and money it will take? Your board will face pressure from investors to find quick fixes. So it’s important you help them gain deep conviction that your strategy is sound. You’ll need their support through thick and thin.

You are sure to encounter early resistance throughout the organization. Remember the systems archetypes presented in Chapter 8? Archetypes such as policy resistance, escalation patterns, rule beating, leadership as enablement, the tragedy of the commons and so forth will pop up. To successfully address them, your strategy must unfold in stages. At each stage, you need to consider the people, workflows, technology and money flows that you will impact. Consider the perspectives of all stakeholders in your intervention design, and then bring people along (or, if necessary, replace them).

Stage 1: First Projects

To rediscover generative DNA, is best to start with sustaining innovations tied to your existing product. These are simpler and have a higher chance of success. Get into your customer’s world. Study how customers use your products and services today. Challenge exploratory teams to bring an “extreme outside in” point of view. Find out why prospects buy and don’t buy, and what is making existing customers frustrated. Don’t just look at product features — consider the business model. Is it working for customers? Study the data. What are product feature usage rates? What can we learn from churn data? NPS scores?

These immersive experiences with customers and prospects, augmented by data analysis, will help you zone in on existing product frustrations, emerging needs and potential innovations. These insights will inform the product road map. With new features prioritized, you can then increase investment in product management teams so as to accelerate their development and launch.

While the technical details will be covered later (in Chapter 28), digital transformation comes down to migrating from a monolithic world into a microservices world and then embracing relevant emerging technologies. It occurs in many small steps. The first project, one often executed with the help of a consulting firm such as Accenture, is to map out the enterprise’s systems and domains, comparing current and future state. How do we leverage technology in our products today? How should we do so tomorrow? How does technology improve internal workflows today, and how should it tomorrow?

This project will provide an enterprise overview of product and process-related technology gaps. As you assess these gaps, you will make determinations as to where the gaps are most significant, where the need to close them is most urgent, and which improvements are technically easiest and hardest. This data will help you select where to start.

Your goal will then be to start small. You’ll build a small new technical environment that sits outside of the monolith. Your first project might well be in support of a product initiative. It should be a relatively simple initiative, where the monolith dependencies are not complicated. You’ll assign a technical team to the project with the competencies to build and manage the data layer, application layer, integration layer and a cloud-based infrastructure layer. When complete you’ll have your first technical domain that sits outside of the monolith. You’ll also have a self-organized, autonomous technical domain team that can work independently, without needing to coordinate with monolith managers. This organizational building block will be replicated again and again as the monolith migration progresses.

Stage 2: New Product Experimentation, Infrastructure Improvements, Customer Experience Expansion and First Adaptive Projects

At this point, you might begin to mobilize “horizon three” investments — those that seek disruptive innovation breakthroughs. Initial investments should be small. When an experiment shows life, you invest more. As traction emerges, you invest more again — a prove it-or-lose-it investment approach. The purpose of these investments is not just to hit the jackpot with a big new product breakthrough. It’s also to learn — from both failures and successes. The very act of engaging the market with new product ideas yields rich feedback loops that will help inform your next steps.

Disruptive innovation experiments include corporate venture investments, skunkworks projects (often run through incubators and accelerators), and other business unit new product initiatives. In the beginning, an experimentation team may be comprised of just two or three highly talented, ambitious people. It’s best to mobilize multiple teams simultaneously, with each exploring a different high level product thesis. These days there are incubators in cities all over the world, happy to welcome such teams from global 2000 enterprises.

If you are a B2B company, consider entering into experiments in partnership with one or more of your visionary customers. That way the customer’s perspective is involved in product ideation right from the get go. You might even consider bringing your business customer in as a co-investor in these experiments. Perhaps you might spin up multiple exploratory teams at once, and then join your customer in reviewing the concept pitches and deciding which ones to invest in.

Just as early stage venture funds do, be sure to create enough investments to spread the risk. A typical early stage venture fund will execute twenty investments — about five per year for the first four years of the fund. For a successful VC, the rule of thumb is that ⅓ of these investments will lose all their money, ⅓ will break even and ⅓ will yield attractive returns — with perhaps one or two of them turning into very successful companies.

As experiments prove out, you will have to decide how to manage them. You can run them as separate companies, free to take outside investment. You can retain them as wholly owned but independent subsidiaries; or as part of an existing business unit. There are advantages and disadvantages to each approach. As a general rule, the more you run them like independent startups (with a similar risk / reward profile for the team) the better.

Eventually, innovation teams will want to leverage the enterprise’s market access to accelerate growth. But be careful. Make sure your integration steps yield the benefits of enterprise leverage without the baggage of enterprise bureaucracy.

Most new products will include digital features, built by a technical team. As the technical team builds out the data layer, application layer, integration layer and infrastructure layer required to deliver the features, it will do so independent of the monolith. The work of these teams advances digital, as well as generative, transformation.

Soon you will begin to work directly on monolith migration. The first step will be to choose a module inside the monolith to move into a microservice on the cloud. Once the first module is successfully cleaved from the monolith, you will move on to the next. Soon the number of technical teams managing services outside the monolith is growing. These new teams are early adopters of an emerging new product and engineering culture.

Stage 3: The Big Move

By now, the migration of your technical infrastructure is well underway. Multiple cross-functional technical domain teams are managing microservices in the cloud. They are seeking to advance domain-specific business objectives in a self-organized way, leveraging disciplined agile delivery methods, with weekly software updates. Some domain teams are at work on the enterprise’s legacy products, building digital leverage into various stages of the customer experience.

But friction is rising.

The culture and methods of new technical domain teams have begun to clash with monolith engineers. Monolith engineers have worked within formal approval processes, the waterfall development method and occasional large releases in a control-based, process-centric paradigm. Now these new technical teams are challenging the paradigm. Old and new don’t get along.

For some, a mental shift has begun. Some legacy workers observe the success of early monolith migration steps. These new distributed systems, built on the cloud, are delivering big improvements. It is now possible to update these systems with small releases much more frequently. The pace of software development has accelerated. Uptime has improved. Failures still occur, but they are small, contained and quickly recoverable. Software components can even self-heal. And compute cost has dropped significantly.

In mid management, legacy technical leaders and the leaders of the new technical domain teams speak different languages and share an uneasy coexistence. Debates center on questions of control, security and data protection. The legacy leaders know their skills and experience are misaligned with new expectations; the best of them have begun to bridge the knowledge gap.

Similarly, business unit leaders struggle to guide the new technical domain teams tasked with building digital leverage into the customer experience. These leaders have grown up in a control-based culture. They are used to telling technical teams what product features to build. They are struggling to adjust to the new paradigm, in which leadership’s role is to assign business outcome expectations and to allow teams to figure out how to achieve them. Some leaders can’t adapt. People have begun to take note that when a leader gets in the way of change, he is replaced.

At the executive level, conflict has bubbled up between the inner circle executives fully committed to the transformation, and those who have been maintaining the legacy business. As new ways of thinking and new digital capabilities expand beyond their initial beachheads, legacy executives discern that they must adapt or leave. As CEO, you are starting to figure out which leaders are becoming In The Loop leaders, and which are not. You’ve begun to act on your assessments. Executive team membership is changing.

The preparatory stages are over. It’s time for a decisive move. There are two possibilities (not mutually exclusive):

- Execute a material acquisition (for instance, if yours is a $3B revenue company, you buy a $50M+ revenue company )

- Hire new top leaders and reorganize

With an acquisition or a major reorganization, success depends on a certain type of executive. I call this person a “bridge player.” Bridge players are those unique and rare executives who deeply understand the legacy enterprise (including its communication patterns, hidden power dynamics and systemic constraints) while also understanding the new vision and road map. They are uniquely capable (in no small part because of strong emotional intelligence and collaborative skills) to bridge the old and the new, and to help legacy players make the shift to a new mindset.

Big Acquisition

The right acquisition can superpower your generative and / or digital transformation. In 2016, General Motors acquired autonomous vehicle technology startup Cruise Automation, which now comprises the core of its self-driving unit. Since the acquisition, the company has directly and indirectly invested over $3B into it. For GM, the acquisition has advanced its generative transformation by turning it into a leader in self-driving cars. And it has advanced GM’s digital transformation by giving it ownership of a large technical team leveraging the latest AI, machine learning and IoT technologies in a cloud based reactive microservices architecture with modern data infrastructure.

Many global 2000 enterprises have followed suit. Walmart has acquired a number of ecommerce retailers, including Jet.com, Moosejaw, Bonobos and Modcloth. In 2017, IKEA acquired TaskRabbit. In a 17 day span in 2015, Boeing bought an aerial imaging company, Spanish bank BBVA bought Spring Studio (a company focused on the online user experience), and Mastercard bought an analytics company (Applied Predictive Technologies).

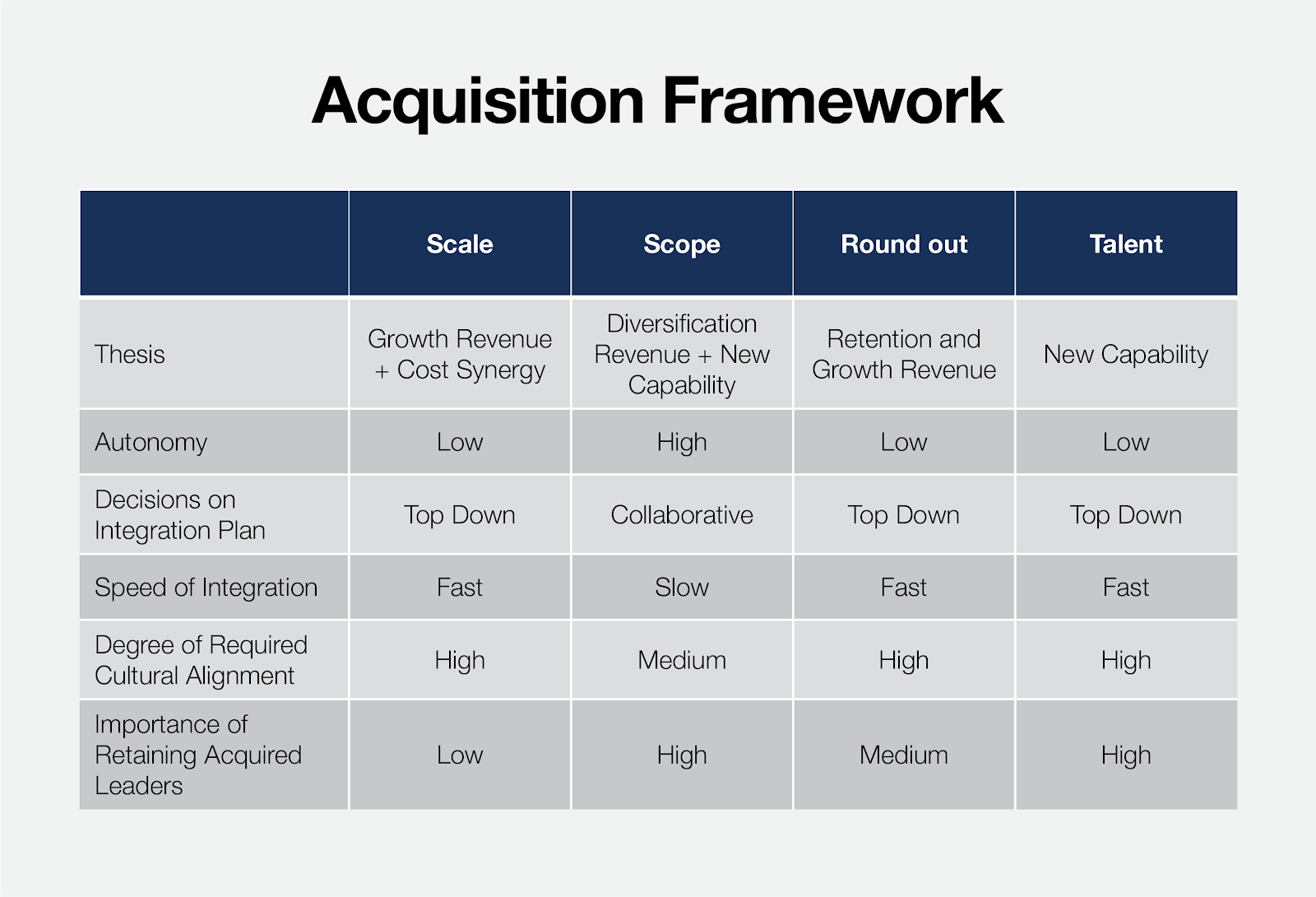

There are four types of acquisitions:

The type of acquisition most relevant to enterprise transformation is the scope acquisition. In a scope acquisition, the company you acquire possesses product capabilities and other assets your enterprise needs and doesn’t possess. A well conceived scope acquisition can become a decisive lever for change. GM’s acquisition of Cruise Automation was a scope acquisition.

But there’s a problem: most acquisitions don’t work. Research shows that a high percentage of acquisitions fail. Indeed, Harvard Business Review researchers quipped that M&A deals should come with a warning label: “Acquisitions can result in serious damage to your corporate health, up to and including death.”⁸

The key to success with a scope acquisition is to protect the acquired company from being subsumed into the enterprise culture faster than its leaders want to be. Simple things like hiring processes, compensation boundaries and security and compliance requirements can tie the newly acquired team up in knots and cause the most important people to leave. That’s why the “bridge player” role is so important.

After the acquisition of Cruise Automation, GM placed the company directly under Dan Amman, at the time GM’s president. He was a bridge player. He ensured that Kyle Vogt, CEO of Cruise, and his team were protected from mothership encroachments. Executives and managers inside GM were informed they could not reach out to people at Cruise. Hiring and firing practices, data controls and cultural expectations were kept separate.

Then, after two years as a completely separate company, when it was time to begin taking advantage of GM’s vehicle production capabilities and market access, Dan Amman stepped down from the presidency of GM to become CEO of Cruise Automation. Kyle Vogt moved to the CTO role. After having successfully protected the acquisition and held onto the top team, GM placed a bridge player at the top of Cruise — someone who deeply understood the culture, vision and status of Cruise as well as the culture, vision and status of GM. CEO Mary Barra began putting in place more bridge players on the GM side — for instance, in vehicle manufacturing — who could manage the intersection points between Cruise and legacy GM.

I have written about acquisitions in two previous books (People Design — Chapter 20; Funding & Exits — Chapter 14), so I won’t repeat myself. Suffice it to say that in an acquisition you need to solve for the following risks:

- Lack of clarity in the acquisition thesis and its strategic implications

- Inadequate pre-acquisition due diligence, resulting in negative surprises

- Failure to define the desired degree of autonomy (from mostly separate and stand-alone, to highly integrated)

- Failure to establish a new vision for the culture, both within the acquired entity and the acquiring company

- Failure to develop a comprehensive integration plan

- Failure to adequately resource the integration team and project

- Failure to place the newly acquired company under a leader who is aligned with the planned degree of integration and the sustaining culture

- Failure to execute ongoing management decisions consistent with the agreed degree of integration and culture

- Failure to communicate effectively at all levels, throughout the acquiring and the acquired company

- Failure to maintain momentum in executing the integration plan

Change at the Top or Big Reorganization

You can also shake things up by bringing in new top leadership, or through a big enterprise reorganization.

Legos is a seventy year old company. In the 2000s, home video games began to cut into traditional Lego sales. The company’s initial attempts to respond (such as Lego theme parks, a Lego clothing line and toy changes such as bionic toys and toys focused on girls) were largely unsuccessful. Jorgen Vig Knudstorp was brought in as the new head of strategy. He first sought to drive changes within the existing structure, with some success — but the external headwinds were significant enough that the board made him CEO in 2005. Knudstorp broke the company down into separate business units, each of which was challenged to stand on its own. He hired new leaders, moved from a fancy headquarters into a warehouse, advocated a startup mentality, recruited Legos customers into the product development experience and began a digital transformation.

To create transformative change, you will need to execute some bold moves. It may be a new CEO or senior executive, a big reorganization or one or more large acquisitions. No matter what the big move is, it is sure to carry risk as well as opportunity. Here too, you will need bridge players who understand the legacy business but also buy into the new vision.

Stage 4: Inversion

At some point in the journey, a shift will occur. On the executive team, everyone is bought in. Every executive is working hard to increase digital literacy and systems thinking skills. As CEO, you have begun to articulate to all employees new cultural values and expectations: customer centricity, generative first / adaptive next, systems centric, business outcome focused, high performer focused, transparent, data-driven, agile and self-organizing. Mid managers throughout the company have taken note of the changes around them, and are seeking to adapt.

You will know you have hit the inversion point when you begin to see mid managers and teams acting on their own to drive the change you seek. Business units are now organized in a systems-centric organization structure, with both uni-functional and cross-functional domain teams. These teams begin to demand access to better data to track their own performance. You find yourself spending less time achieving buy-in, and more time working to uplift the meta systems: the DataOps system, engineering system, culture system, strategy / planning / architecture system, and the governance system.

You’ll begin to observe people throughout the enterprise acting to advance the vision. Throughout the company, teams seek to purge aberrant behaviors, such as:

- Placing process above results

- Focusing on efficiency at the cost of resiliency and scalability

- Trying to measure engineer productivity

- Slowing down the transition of the monolith to the cloud

- Demanding long-term plans from experimental innovation teams

- Fighting innovation projects that threaten the core

- Pushing a functional agenda that conflicts with system requirements

- Seeking to centralize decision making

- Killing new acquisitions with excessive bureaucratic processes

That’s an inversion. Change is now driving upward and outward, not downward from the top. Domain teams and their leaders are pressing you and other top executives for new investments and support to accelerate change.

Stage 5: Optimization

And then one day, years after your first baby steps, you wake up and realize you have become a digital-at-the-center, fit systems enterprise. Of course, your company is far from perfect. Problems small and large continue to arise. But now feedback loops throughout the ecosystem and enterprise keep you in the loop. Leaders see the integrated nature of things, and possess the digital literacy to know where technology can help. They act on their own to improve.

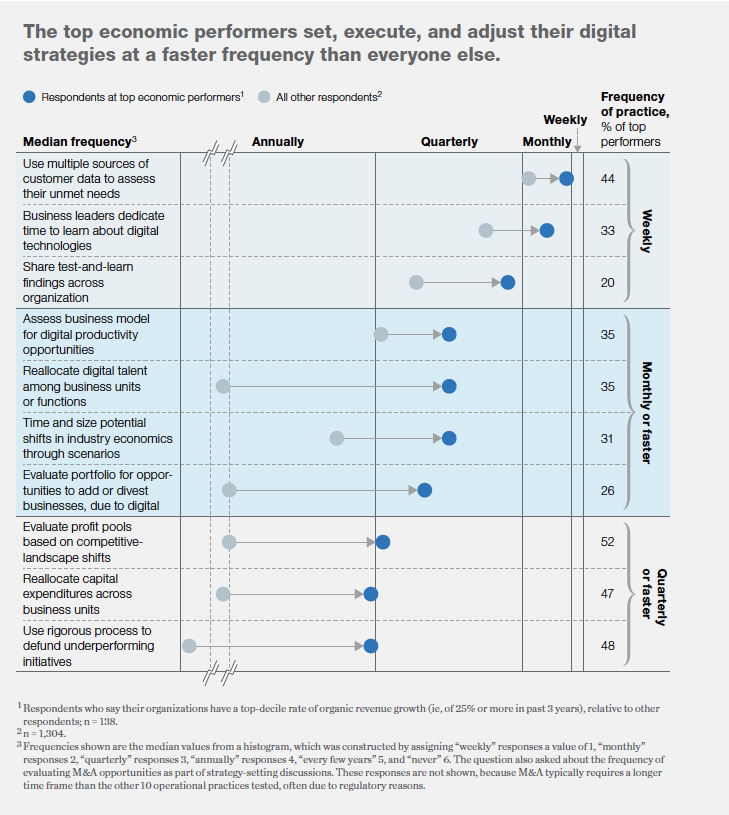

McKinsey & Co., in a recent report on digital strategy⁹, compares top performing companies to all others in their development and execution of digital strategies:

SOURCE: Bughin, Jacques, Catlin, Tanguy, and LaBerge, Laura. “A Winning Operating Model for Digital Strategy Survey”, McKinsey & Co.,January 2019.

As CEO, you focus more and more on the meta systems. You seek to push data to every corner of the enterprise (the DataOps system). You work hard to ensure technical teams possess the tools and agile methods to build and maintain great digital solutions (the engineering system). You evangelize the culture, and work to ensure you increase the density of 10Xers in all high variation domains (the culture system). You regularly revisit your bounded purpose, build strategy informed by feedback, and cascade strategic imperatives into system and domain-level OKRs, continuously working to increase alignment (the strategy / planning /architecture system). And you work with your board and executive team to continuously advance your vision, always balancing now, near and far (the governance system).

The biggest problems come to you, the CEO. But because you are now a fit systems enterprise, the problems have become more interesting.

To view all chapters go here.

If you would like more CEO insights into scaling your revenue engine and building a high-growth tech company, please visit us at CEOQuest.com, and follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter, and YouTube.

Notes:

- Moore, Geoffrey. Zone to Win: Organizing to Compete in an Age of Disruption. Diversion Books, 2015.

- Harvard Business Review. “What The Companies on the Right Side of the Digital Divide Have In Common”, by Robert Bock, Marco Iansiti and Karim Lakhani, January 31, 2017.

- McKinsey Quarterly article. “Why Digital Strategies Fail”, by Jacques Bughin, Tanguy Catlin, Martin Hirt, and Paul Willmott, January 2018.

- Dimensional Research: 2019 IT Architecture Modernization Trends: A Survey of IT Executives at Large Enterprises, July 2019.

- Reported in a Forbes.com article, “Where Most Companies Go Wrong in Digital Transformation”, by Peter Bendor-Samuel, July 18, 2018.

- Dimensional Research, op. cit.

- Reported in From.Digital, “Why 84% of Digital Transformations are Failing”, by Bob Taylor

- Lewis, Alan, and McKone, Dan. “So Many M&A Deals Fail Because Companies Overlook This Simple Strategy.” Harvard Business Review, 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/05/so-many-ma-deals-fail-because-companies-overlook-this-simple-strategy

- Bughin, Jacques, Catlin, Tanguy, and LaBerge, Laura. “A Winning Operating Model for Digital Strategy Survey”, McKinsey & Co.,January 2019.