The trade show floor is bursting at the seams. So too is SparkLight Digital’s booth.

Just this morning, you took part in four successful dealer group meetings. Victor arranged them beforehand, in each case with the dealer group principal, and asked you to attend. Three out of four principals agreed to a full demo with their decision teams at specified dates and times, already booked on calendars.

These dealer group meetings signal a welcome new stage in the growth of SparkLight Digital. Joe, Vijaya, Beatrice, Farook and the rest of the engineers and product managers accomplished a ton of work on the product. They spent the Spring and Summer working towards the goal of launching SparkAction CRM 2.0 just before this trade show. This updated version features new reporting capabilities, including dealer group analytics and social reputation management capability. The addressable market expanded with these new features in place. SparkLight Digital can now pursue multi-store dealer groups and single-store dealerships.

The booth is stunning. A bright, welcoming display greets the visitor with “Gain the Spark to Spike Sales” emblazoned along its top. A large triangular “SparkLight Digital” sign hangs from the ceiling. It provides instant visibility to anyone walking the floor because the booth location is right at the intersection of two key traffic corridors. Racks hold neatly organized collateral materials. Everyone is wearing the same shirts in SparkLight colors. The booth has enough space to accommodate multiple simultaneous conversations — precisely what’s happening now.

At this moment, you engage a dealer group principal from the Midwest. He happened by your booth as you freed up from another conversation. To your left, Victor is breaking down features and benefits with the owner of a large San Diego Ford dealership. Beside him, Serena engages a Toyota store GM. Her arms are flying and smile radiating; she holds the GM transfixed. Elsewhere, the SDRs and AEs occupy themselves with prospects.

Of all the scheduled appointments, only one dealer group principal was a no-show. Bobby Petrak, CEO of Incline Dealer Group, was on for a 10 AM meeting this morning, but he didn’t make it. Too bad. Of all scheduled appointments, he represented the largest dealer group. Petrak runs a sixty-five store group based in Florida. Securing a meeting with him in the lead-up to the trade show was a significant accomplishment for Victor.

Altogether, thirty-six signed contracts are already in hand. Three are from dealer groups. In aggregate, these contracts represent sixty-two stores signed. It’s more than you expected, and there’s still one more day to go. The trade show is turning into a huge success. A public announcement interrupts your conversation with the dealer group principal from Milwaukee: “Lunch will be served in the Holman Ballroom in 10 minutes. All attendees should please proceed now to the Holman Ballroom.”

As conversations wrap up and dealers peel away, you look around the booth. Victor, Serena and the six SDRs and AEs look exhausted but happy. You all head off to lunch together. Once in the ballroom, you disperse so you can meet, greet, and eat with more dealers. No rest for the weary.

Forty-five minutes later, you and Victor stroll back through the hotel past the many side conference rooms that surround the exhibit hall. Just as you’re about to turn into the exhibit hall and back towards your booth, you notice Serena. Inside one of the small conference rooms to your left, she’s standing in front of a screen sharing a PowerPoint presentation with someone. After a quick peak, Victor steps into the room. You follow.

Inside, caught mid-presentation, Serena looks up. In front of Serena sits Bobby Petrak, CEO of Incline Dealer Group. “Bobby, good to see you. We missed you this morning,” Victor says.

“Oh hey, Victor. Yeah, I had something else come up. But Serena here caught me at lunch, so it looks like you’re getting my attention after all!” he says with a broad smile.

You step forward to shake Petrak’s hand and introduce yourself as the SparkLight Digital CEO. You ask to sit in; Petrak agrees. Serena smiles and returns to her presentation. “Now as I was saying — ”

At that moment, Victor strides up to the front of the room, shouldering Serena aside. “Good then. Let’s proceed.” As Serena flushes red and you cringe, Victor starts the pitch over, from scratch.

. . .

The marketplace is cold and unforgiving. In it, your enterprise coexists with other competitors — all seeking advantage. To survive and thrive, you must deliver value to customers in ever expanding ways. As you pursue advantage, your enterprise brings strengths and vulnerabilities, opportunities and threats. To grow, you must fortify your strengths, mitigate your weaknesses, pursue your opportunities, and fend off your threats. These imperatives inform strategy which informs objectives and tasks.

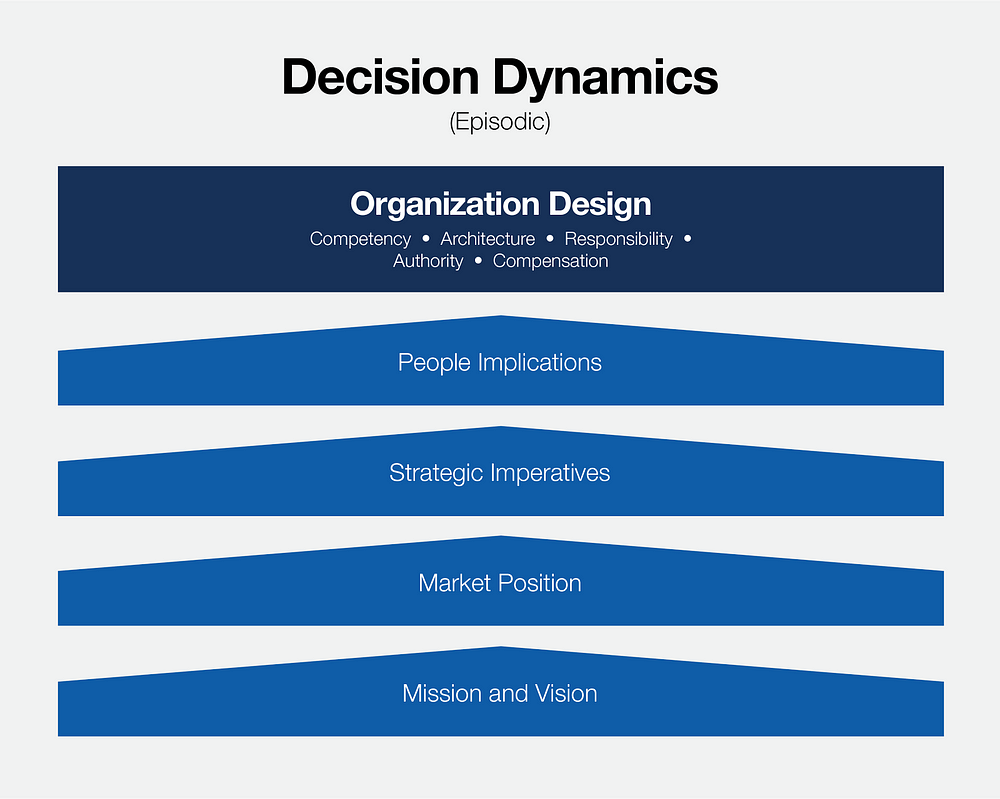

Organization architecture matches human talent to business strategy, objectives, and tasks. Successful architectural design supports the flow of a leader’s directional, executional, and moral voice. It is a primary output of the Decision Dynamics section of the People Design Framework.

Organization architecture is more than just the organization chart. It is this, for sure — the hierarchy of roles, titling, dotted line vs. straight line, levels of staffing, and definition of the vertical business units vs. horizontal functional groups. But it is more. Architecture also addresses the delineation of project teams and workflow groups, committees, the contractor/employee mix, the population of headquarters vs. field offices, the balance of onshore vs. offshore, proximity decisions inside the workspace, and even the physical design of your office.

Consider a planned office building. The architect identifies the owner’s functional needs and aesthetic aspirations. How many offices will be in the building? How many conference rooms? What design objectives does the owner have? What’s the budget? The requirements list goes on and on. Based on these, the architect unifies aesthetic and functional goals, rendered in a detailed set of drawings. The drawings include a comprehensive visual design, a sound structural design, a design for water, plumbing, electricity, and HVAC, and a myriad of details specifying materials and assembly. Together, these guide you to create a beautiful, safe, efficient, and functional building.

So too, as CEO, you must architect your company. The quality of your organization architecture is a significant factor in the effective pursuit of strategy, objectives, and tasks.

To begin, you must consider a series of requirements and constraints:

- Your stage of company

- Your budget and access to cash

- The market segments you serve and the business models each requires

- Your need to hit immediate performance objectives vs. freedom to build for future performance

- The degree and nature of transformation needed (e.g., product/market fit and revenue engine maturity)

- Your competency assessment (the enterprise’s competency gaps; and the current task-relevant maturity of executives, mid-management, individual contributors)

- Your workflow collaboration requirements (functional and cross-functional)

- Empowerment you require (at every level)

- Your efficiency objectives

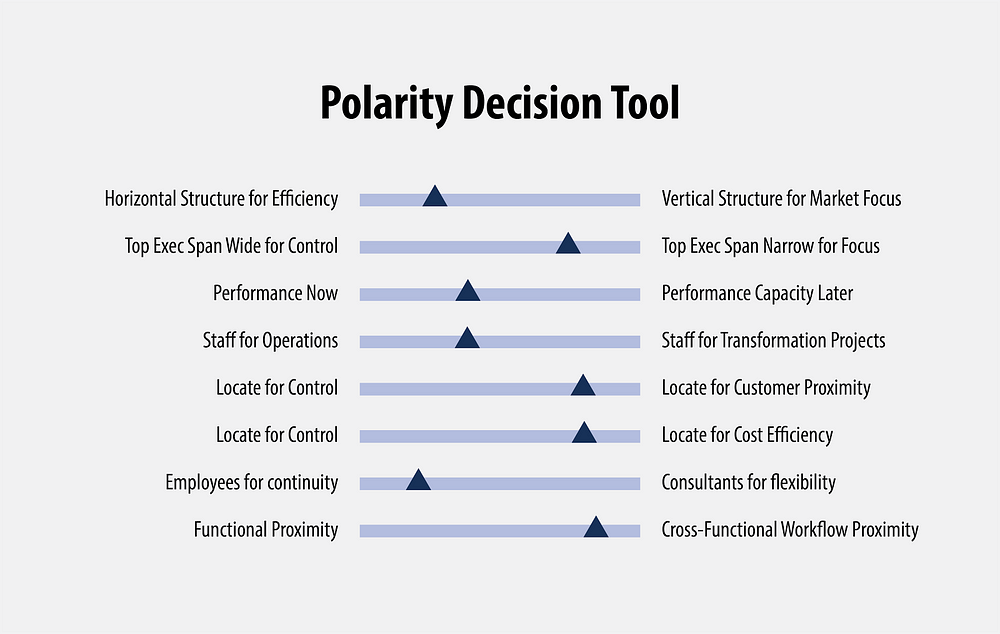

Expect to resolve a steady stream of tradeoffs. Time and time again, you’ll realize the tension between goals. Do you build for current operational execution, or to support work on transformational projects? Should you place all employees in one office, for coordination and oversight, or is it better to put employees in multiple cities, close to your customers? Do you want engineers to collaborate side by side in Silicon Valley at headquarters, or will half your engineers work in India, where you gain a significant cost advantage? Given your customer service requirements, do you build for control, or build for empowerment? Do you create separate cross-functional business units for each vertical you serve (customer centric), or build functional marketing, sales, and operations groups that work across verticals (efficiency/control centric)? Do you “buy” employees or “rent” consultants? Do you widen span of control to achieve integrated decision making, or narrow span of control to achieve focus?

These dilemmas are polarities. Polarities are not binary choices — they comprise a continuum between two poles. It’s helpful to create a polarity decision tool to guide architectural decision making. Here’s an example:

As you ponder the decision factors, you judge the optimal point along each polarity. At different moments in time, the point you choose on the polarity continuum may be different. But each time you must choose. Polarity choices inform:

- Functional composition of your executive group

- Titling

- Reporting relationships

- Span of control (each executive’s scope of responsibility and authority)

- Positions, titles, scope, reporting relationships, and staff levels of all roles under each executive

- Whether there will be business units organized around each market vertical, and if so, what functions will reside in them (and which will run horizontally, cutting across them)

- Any dotted line relationships (for instance, between business unit sales leaders and a corporate sales leader)

- Power relationships between straight and dotted lines

- Headquarters/field offices mix

- Headquarters/offshore mix

- Employee/consultant mix

- Need for and composition of committees

- Formation of workflow groups

- Proximity decisions — who sits near whom

- Project team membership (given strategic imperatives)

- Office design

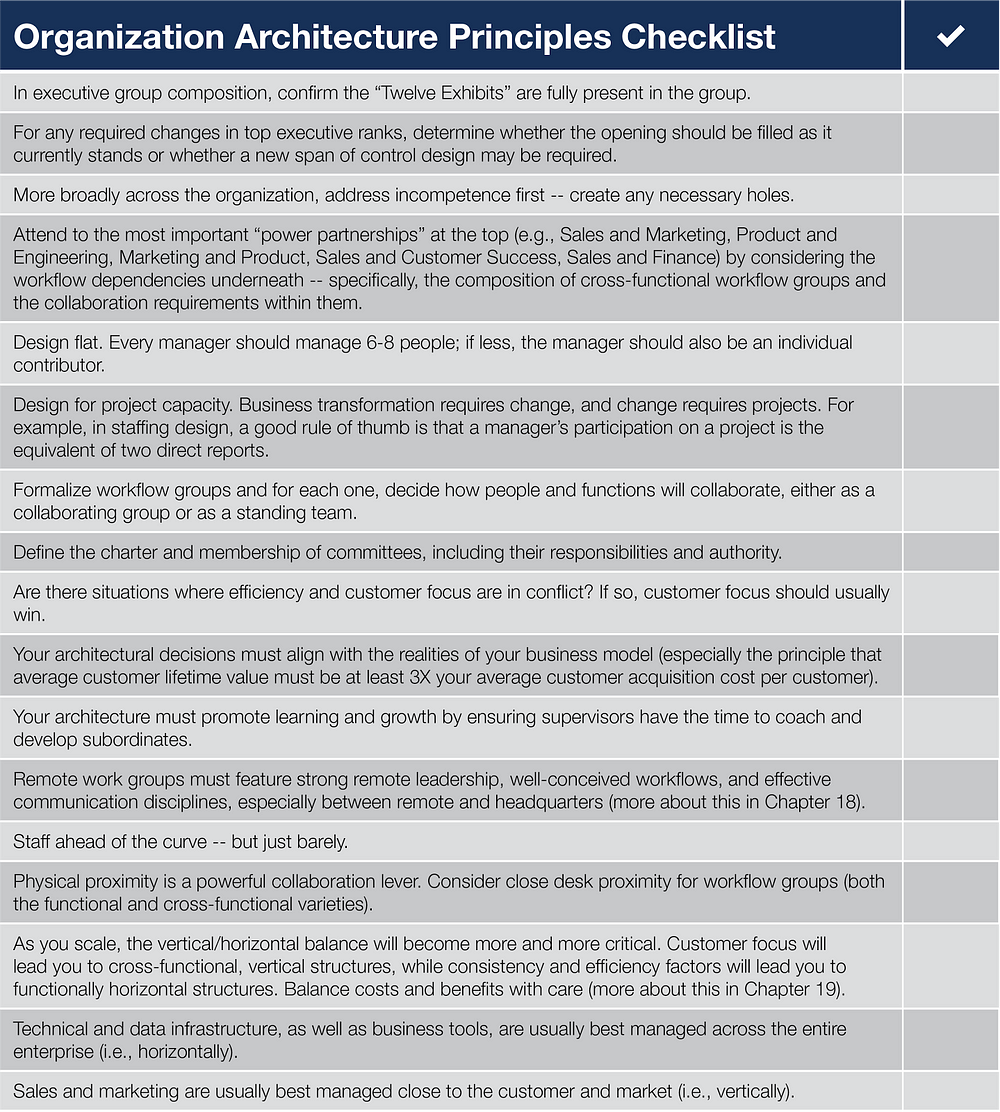

Be careful with expedient decisions that may have negative consequences. Ben Horowitz’s notion of “management debt” (akin to technical debt) is relevant here.¹ You might give a new hire an inflated title out of sync with other roles just to assuage the hot candidate you’re desperate to secure. Or you might widen span of control to meet an executive’s advancement objectives despite introducing power misalignments and dysfunction into the executive group. Or you might place the Engineering group, which yearns for peace and quiet, right next to Sales, which is a beehive of noise and activity just because it was the easiest move to make. These are examples of management debt.

A CEO’s work on architecture design begins with a clear-eyed view into the company’s current market position and growth requirements. This perspective yields the strategic imperatives, people implications, and role-by-role competency assessments that guide architecture design. The aspirations of top job candidates and key incumbents are a factor every CEO must take into account. However, company need drives most decisions on role scope, title, vertical/horizontal structure, reporting relationships, and office size.

Management debt is all too common. Poorly thought through architectural decisions cost you leadership leverage and introduce needless friction into your company. To avoid management debt, a CEO must exercise both vigilance and discipline.

Consider the following checklist:

The process you follow to complete a new architectural design depends on both circumstance and culture. If you are the new CEO replacing the founder of a stalled-out tech startup, you are more likely to lean towards control. You gather the facts as best you can, but the competency assessment and critical architectural decisions are yours to make. If you lead a fast-growing startup that needs new organization architecture to power the next stage of growth, your approach to design is likely to be more collaborative. The decision process is an important choice. It impacts the acceptance and support your final architectural decisions receive. So choose with care.

. . .

Victor never got through his pitch. About 10 minutes in, Bobby Petrak stood up and announced, “Victor, Serena already covered everything you’ve just told me.” He looked at his watch. “I’ve got to go — I wasn’t planning on this right now anyway. Serena button-holed me at lunch and I said I’d give her a half hour, but I’m not interested in hearing the same pitch twice.” He shook hands with you, Serena, and Victor as he communicated his “no thank you” with a tight formal smile.

The moment he left the conference room, Serena walked to the door and closed it. She turned to you and Victor. “We need to talk.”

It is a difficult conversation. Serena stands and stares at Victor. She delivers her message with blunt force. “Never do that again,” she says. “I am your peer, not your puppy to be kicked to the side.” Victor stands up and pushes back, his voice rising. He argues, “I’m the head of sales: not you! Petrak was my — ”

You cut him off there. “Victor, sit down. It’s my turn. I must tell you I’ve never seen a senior executive exhibit such disrespect to a peer. It is completely unacceptable, and it can never happen again.”

You continue. “Serena, can you give Victor and me a minute?”

She picks up her laptop and backpack, then closes the door behind her as she leaves.

“Victor, what were you thinking?”

“I worked for two months to get a meeting with Petrak. I did the research. I had the data on the issues in his dealer group. I . . . ”

“Victor, listen to me. I don’t think you realize the significance of what you just did.” You take a breath.

“Not only did your action undercut Serena’s presentation and lose us this deal, but you also undermined the critical trust we need between Sales and Marketing. If we can’t build a strong, trusting, collaborative relationship between the two of you, we won’t get anywhere. The burden is on you now, Victor. I am sorry to tell you this, but disrespect is a fundamental problem for me. It cuts to the core of who we are. If you can’t build a respectful, strong, and productive relationship with Serena, then I will find a new head of Sales. Figure it out. Fast.”

You walk out of the room.

. . .

Notes:

- Ben Horowitz, “Management Debt,” allthingsd.com (blog), January 18, 2012, http://allthingsd.com/20120118/management-debt/.

. . .

Please visit us at CEOQuest.com to see how we are helping tech CEOs of growth-stage companies achieve eight-figure exit value ($10m+).