The $500,000 in new investment from Anik is burning fast. Six months have passed, and the apartment is crowded. Three desks, five people. Bill and Farook, two recently hired engineers, have been hard at work. The product is fast becoming fit and trim. You note with satisfaction that Joe has been providing Bill and Farook solid engineering direction. Now that engineering can keep up, Vijaya’s work on the UX has picked up. Four auto dealers — three Toyota and one Ford (featuring three different CRM systems) comprise your beta customers. Despite adding new integration permutations, the bugs have declined. The GMs at all four stores seem pleased to see actual price quotes flying out to prospects promptly. Things are trending in the right direction.

. . .

Robert Pirsig wrote the book “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” in 1974. It became an instant classic. In the midst of his story about motorcycle maintenance, a motorcycle trip, and the relationship between a father and a son, Pirsig held forth on the essence of Western and Eastern philosophy. Amongst many other deep metaphysical insights, he concluded that Western philosophy, if reduced to a single word, would distill to “quality.” And Eastern philosophy, in a word, would render as “caring.”

But quality stripped of caring is the atom bomb. And caring stripped of quality is benevolent chaos. It is only in the union of quality and caring, Pirsig said, that one becomes fully present in the totality of experience. Only once one’s rational and emotive sides are equally and fully engaged can good work proceed on good things in good ways.

He wrote, “Care and Quality are internal and external aspects of the same thing. A person who sees Quality and feels it as he works is a person who cares. A person who cares about what he sees and does is a person who’s bound to have some characteristic of quality.”

Caring and quality are the two most essential virtues underlying a leader’s moral voice. As a tech company CEO, you live in a dynamic, multidimensional environment. In your daily acts of company-growing, you must make a stream of strategic, tactical and interpersonal decisions. These decisions shape the future of the company. They impact every person in the company’s orbit: employees, investors, customers, and vendors. And because of that, they shape you. In this myriad of decisions, moral voice speaks loudly.

Who you are affects what you do. What you do affects who you become. So in this exploration of people design, it makes sense to start with You. To be a great leader, you must first work on yourself. Inside out — that’s the proper order of things.

Bill Campbell’s character was perhaps best revealed by his leadership of GO Corporation in the late eighties and early nineties. GO was a VC darling that attracted $75M in funding. When Campbell became CEO, he inherited a strong team — including Vinod Khosla, subsequently the founder of Khosla Ventures; Randy Komisar, who became CEO of LucasArts and is now with Kleiner Perkins; and Omid Kordestani, who went on to become SVP Global Business at Google; to name a few. But under Campbell’s leadership, the company struggled with technical challenges, faced strong competitive headwinds from Microsoft, and posted scant revenues. Ultimately, GO couldn’t go and was eventually sold for parts to AT&T.

Campbell moved on from GO’s disappointing run. Scott Cook, founder of Intuit, recruited Campbell to be Intuit’s next CEO. The company had recently merged with a similar-sized company. Two cultures — two different teams — two sets of egos. The integration challenge was daunting. The mission was to turn these two separate teams into one. In Cook’s words, Campbell “did it beautifully.” He worked tirelessly to build trust and dissolve old boundaries. He taught each executive to depend on and sacrifice for the new team. “The best definition I know of what is a leader is that he inspires people to become followers,” Cook said. “Bill Campbell did just that.”

Intuit was a success. Certainly, we can learn much about leaders from their successes. But GO was a failure. Leadership is most greatly tested in failure. How is it that, to a person, every executive who worked for Campbell at GO was so high on him? All of these executives speak with passion about the impact Campbell made on their lives. The words and themes that emerge in interviews are remarkably consistent: “showed me what integrity really means,” “selfless,” “taught us to become a team,” “cared about me as a person,” “father figure,” “my closest friend,” “the person I strive to become.”

On stage at a Silicon Valley event, Khosla once told the story of a beer bash at GO. Campbell had just flown back to San Francisco from a business trip in Japan. The beer bash was Friday afternoon and Campbell had landed that day, having flown through the night. Another trip back to Japan loomed the coming Monday. Yet Campbell showed up at the beer bash. When Khosla asked him why he chose to come, he just said, “of course I need to be here. I need to be here for my team.”

Khosla then told another story — about a biking accident that put Campbell in the hospital with a punctured lung. A dinner with a key customer had been planned for that night, and Campbell was insistent he must find a replacement to attend. He did find someone — but then, halfway through the meal, Campbell himself arrived. He’d slipped past the medical staff. He felt he needed to be there for his customer.

Said Kordestani, “He has been a mentor to so many who have sought his guidance and wisdom on how to be a better leader. He is someone who is so giving despite his busy schedule — always there to help someone. He has spawned such a well-deserved reputation as the coach of Silicon Valley. He’s always authentic. He has a way of boiling down an observation into a saying that captures it all. He’s so real — ultimately companies are about people, and Bill understands that.”

Campbell went on to become the premier coach of Silicon Valley. He coached Steve Jobs. He coached Eric Schmidt and Larry Page. He coached Jeff Bezos and Ben Horowitz. And he coached many other lesser known leaders. All of these luminaries considered Campbell one of their closest friends — a person that had profoundly impacted their outlooks not just on leadership but also on life. Campbell challenged people to be selfless — to sacrifice — to build great teams so as to do great things. One of Silicon Valley’s most successful VCs, Benchmark’s Bill Gurley, said that Campbell’s success rate with the companies he chose to coach was 90% — including two of the most successful companies of all time, Apple and Google.

On the day Bill Campbell died after a long battle with cancer, Horowitz wrote the following:

“Selfishly, all I can think about is how much he helped me and what a true friend I had in Bill. Whenever I struggled with life, Bill was the person that I called. I didn’t call him because he would have the answer to some impossible question. I called him because he would understand what I was feeling — 100%.”

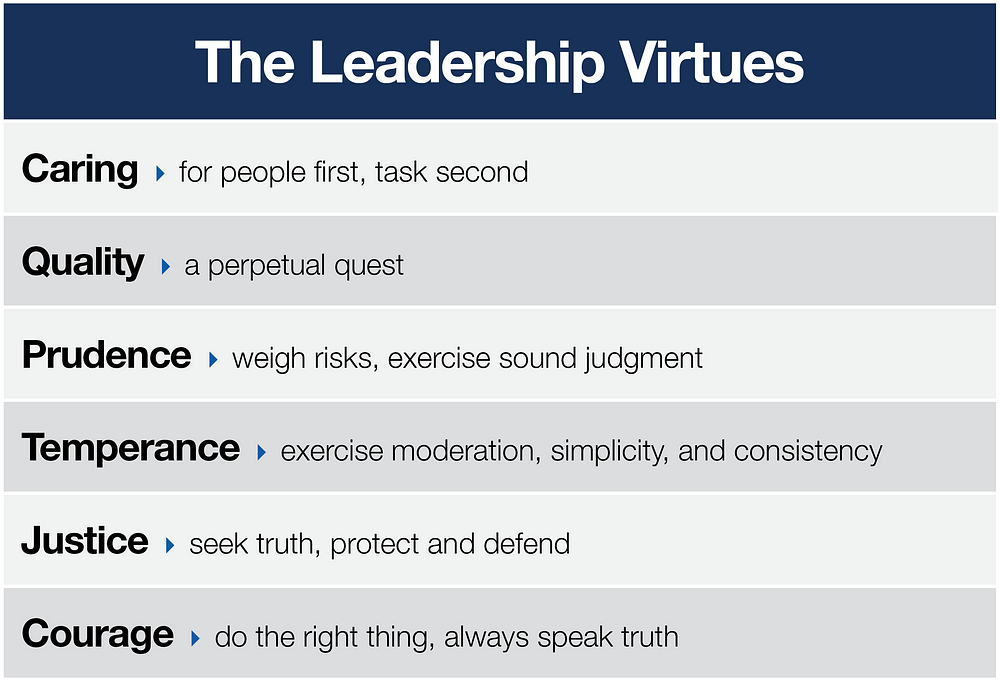

Caring and quality are just the first of a set of virtues that characterize leaders with strong moral voice. Here’s the list:

The final four (prudence, temperance, justice, and courage) find their origins in Plato and Aristotle, but they are echoed in Christian, Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, Islamic and Confucian philosophies. They are universal. They are referred to as the cardinal virtues. Together, these six virtues comprise the moral foundation of leadership.

Many believe that leaders either project a moral voice or they don’t. It can’t be taught, and it can’t be developed. Not so. A leader’s journey along the path of moral development is challenging and lifelong. Character is hard-won. But with purity of intent and the humility of self reflection, a leader’s moral voice can strengthen and mature.

So how does one do it? In his book, “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People,” Stephen Covey articulated the “habits” that align with universal moral principles and help build character. He advocated the development of these habits as a practical way forward in shaping the moral voice. The first three habits build “independence.” The next three build “interdependence.” And the seventh habit emphasizes “continuous personal improvement.” They are:

- Be proactive — your life is designed by you, so determine the person you seek to be and act accordingly

- Begin with the end in mind — have a personal mission statement that captures your core principles — the person you seek to become — and exercise the discipline to plan out each day consistent with that mission

- Put first things first — prioritize; balance projects that produce immediate results with projects that will build capacity to increase future results

- Think win-win — understand the other’s needs and priorities, and think creatively about solutions that deliver mutual success

- Seek first to understand, then be understood — first listen intently; express your truth after you have considered the insights of the other

- Synergize — break down the boundaries between you and the other; tune in to your complementary knowledge; open ideation to great ideas; seek 10X outcomes

- Sharpen the saw — continuously work on yourself

If the leadership virtues are the “what,” the seven habits are the “how.” For anyone who seeks to speak with strong moral voice as a leader, “Seven Habits” is a must-read. Interestingly, in later editions of his book, Covey introduced an eighth habit: “Find your voice and inspire others to find theirs.” Voice is the outward expression of internal growth.

So how does one “sharpen the saw”? Jesuit institutions have nurtured high-character values in their members for over 400 years. Their impact is on every continent. Jesuits built some of the best schools and hospitals in the world. In fact, a Jesuit education shaped many of the world’s leaders over the past four centuries. For Jesuits, much emphasis is on one’s personal development.

In the growth of character, Jesuits believe it is vital to reflect daily on the events of that day. This practice is called the examen. In what ways did I live up to my principles? Where did I fall short? What steps will I take to become a better person tomorrow? For the leader who seeks to project strong moral voice, this daily discipline is an excellent place to start.

Many great leaders have a coach — a person they trust to share their struggles and seek guidance and wisdom. Also, leaders can take stock and foster progress on the journey by taking time to reflect, for instance during a personal retreat or a quiet vacation.

Leadership springs from within. It’s an expression of who you are. Without core principles to guide you, it is so easy to do the expedient thing, to tell the convenient lie, to avoid the difficult truth, to take the easy path. If you seek to be a great leader, you don’t allow yourself to do that. You aspire to be self-aware, and from the insights gained, to work on yourself. You’re honest about your shortfalls. You seek to improve. As moral voice grows, you become obsessed with quality, you begin to care genuinely about others, and you exhibit greater prudence, temperance, justice, and courage under fire.

If this is a journey you are willing to embrace, be prepared. You never reach perfection. In fact, the more you think the cloak of moral virtue is upon your shoulders, the more likely it is you are an emperor with no clothes. To become a great leader, it’s best to just bring a humble commitment to the daily task of rediscovering the best, highest-character version of yourself.

. . .

You have assembled the team together for the weekly huddle around “Desk #1,” the converted Home Depot door. Farook immediately opens his computer. “Farook, we’ve agreed as a team that we will all set aside devices when we meet. That way everyone is fully present,” you say. “OK with that?” Farook nods, and closes the laptop.

You ask for an update on product development. New features are proceeding on schedule. The team seems to be coming together well, following a lean, agile methodology, executing weekly incremental releases. As you wrap up the meeting and head to your car, you’re feeling pretty good. Five minutes later, turning onto the highway ramp, a call comes in that drains the blood from your face.

Farook’s on the phone. “Hey, you know how you told me at our huddle to shut down my computer? The reason I was online was that just before the meeting I noticed an anomaly. Wanted to check it out.”

“What anomaly?” you ask.

“Yeah — it’s bad. It looks like some platform wires have been crossed. For the past three weeks, the user interface for Toyota Brookdale has included a link that goes right into the pricing module for Toyota Rosegarden. The bug must have been introduced during an integration fix. Brookdale has had full visibility into all of Rosegarden’s pricing decisions for the past three weeks. When I compared the two dealerships’ prices over the time period, vehicle type by vehicle type across all vehicles, I noticed that for the past ten days, Brookdale’s pricing has been consistently about $100 below Rosegarden’s pricing. Their sales have spiked accordingly, while Rosegarden has experienced a big sales dip.”

“Oh my God,” you say. “Kill the link!” Farook quickly interjects. “I did already.” He hangs up. You hang your head and weigh your next steps.

The debate begins inside your head, “No one will know we know. The link is now killed; no further damage can occur. What’s done is done. We are barely off the ground — if the Toyota dealer community gets wind of this, it will be a scandal, and no one will trust our platform. If we tell Rosegarden what’s happened, we’ll lose Brookdale, we’ll lose Rosegarden — and news about the flaws in our platform will damage our capacity to sell other Toyota dealers in the region for sure, and maybe even the dealers of other brands. Agh — but it did happen. Damage did occur. Rosegarden lost sales. Rosegarden needs to know. Crap, crap, crap, crap, crap.”

As you walk into the office of the GM at Toyota Rosegarden, you feel physically sick. He sees you hyperventilating. He sees you beating around the bush. His thick eyebrows begin to furrow with irritation. Finally, you confess the issue. You’ve just discovered that your platform had a bug. A competitive dealer was unintentionally given access to Rosegarden pricing, and you believe there has been a significant sales loss for Rosegarden as a result.

He explodes. “What the &%$@?? How the &%$@ did this happen? You little {*#^. What a fine piece of {*#^ you’ve pushed me into. So what are you going to do about it?”

You acknowledge this error was costly. You apologize profusely, taking full responsibility for the bug. You offer to make it right and ask for a second chance.

Forty minutes later, you’ve agreed to write a check for $50,000 to make up for Rosegarden’s lost sales. He’s agreed to give your product one last chance, but he wants the next three months free. Based on monthly fees, it will take three years to get back to break even with this customer. On your drive back home you get a call from Vijaya. Toyota Brookdale has just canceled. The Rosegarden GM must have called the Brookdale GM and ripped his ear off. As you pull into your apartment, your iPhone pings. You see there’s a new post about SparkLight Digital on DrivingSales.com. This site is the leading social media site for auto dealer professionals. The post is a highly negative product review. By a Toyota dealer from Northern California.

Dazed and defeated, you wonder how you will deal with your sudden cash crisis.