The SparkAction CRM security breach might well have been fatal, had it not been for the discovery of the hacker.

By day two of the crisis, with auto dealer customers stuck with a non-functioning CRM system and the critical sales weekend looming, panic set in. Dealers rushed for the exit, desperately seeking a switch to an alternative CRM. Competitors pounced, mobilizing to help dealers convert from SparkAction CRM to their own. When the system finally came back online on day three, the outflow of customers didn’t stop. Within five days, thirty percent of all dealers on the platform sent cancellation notices — half of those had switched already.

But then investigators found the hacker. It turns out it was an engineer at DealerGasket CRM — a direct competitor. This engineer was angry about SparkLight’s rapid growth and market share capture which often came at DealerGasket’s expense. He discovered a flaw in the SparkAction CRM security layer, broke in, and did damage fully expecting he could avoid detection.

News that SparkLight Digital was the victim of corporate espionage by a direct competitor shifted market sentiment even though DealerGasket disavowed all knowledge and terminated the engineer. Dealer customers remained distressed by the state of SparkAction CRM’s security, but with the platform live again, most remaining customers were willing to give you a second chance. You organized an all-customer conference call, where you took full ownership of the breach, apologized, offered two months free for all customers, and announced plans to upgrade platform security.

Joe, Farook, Foster, and Vijaya led the security project. They hired a consultant to complete a ground-up redesign. It took five months of intense work; eventually, SparkAction CRM was the most secure CRM in the automotive marketplace.

The damage, however, was staggering. You were hemorrhaging cash. You lost two entire months of revenue. Even with the two free months behind you, revenue run rate stabilized at twenty-five percent below the pre-crisis level. The product road map was in tatters as security was the only priority.

You realized with dread that you must stem the bleeding. Given recent events, the board made clear another financing round was out of the question at the moment. Your remaining $3M in cash had to last until traction resumed and your story was fundable again. You estimated it would take six months to right the ship. In other words, monthly burn couldn’t exceed $400K. But actual monthly burn was running at over $600K. You and the board were clear about what must happen. There was no choice. You needed to cut costs. Dramatically.

You and the rest of the executive team labored over every expense line item. Compensation was the primary target. First, you decided to cut every VP’s pay to $130K — except you. You reduced your own to $50K. Directors also received a pay cut; all were moved to $110K. But these cuts weren’t enough. You considered an across-the-board pay cut, but in the end, decided that a layoff was the more prudent route. You needed managers and individual contributors focused — not worried about covering their rents and mortgages. Sharp arguments broke out among executives over terminations. But soon these emotions gave way to resignation. By the time decisions were finalized and implemented, thirty employees lost their jobs. Seventy remained. No department was immune.

Between the pay cuts and the layoff, dissatisfaction seeps into the company from top to bottom. You now live in fear. SparkLight Digital’s talent is a source of advantage — with competitors circling, that talent is now at risk.

. . .

Compensation is not just money. It includes base pay, at-risk pay, the equity options grant, the health plan, paid time off, the title, the role, and even spot bonuses and gifts. To devise a compensation system that works effectively is no small feat. It’s easy to screw up, and hard to get right. For that reason, it’s important to start at the beginning — the research into motivation and behavior.

Motivation and Behavior

As CEO, you seek to assemble a talented group of people; assign them appropriate roles, responsibilities, and authority; and ensure they execute on their work with the focus and passion necessary to drive desired results. Towards this end, you want all of your employees to be fully engaged and to tap the outer limits of their human capacities as they execute their roles. Further, you want them to express their gifts within your company rather than leave at the first opportunity to join the competition.

For these things to occur, you must motivate employees towards desired behaviors while ensuring they are engaged and satisfied. In designing a compensation system, it is crucial to understand the impact of compensation on these three factors — motivation, engagement, and satisfaction.

There are two types of motivation — intrinsic and extrinsic. As discussed in Chapter 8, you are intrinsically motivated when your work is like play, when your work has purpose, and when your work develops your potential. Intrinsic motivation is self-actualizing. It prompts behavior with high levels of work engagement. Extrinsic motivation is fear-based. Created by either emotional or economic pressure, it also sparks behavior, but is much less correlated with high engagement.

Writing in the Harvard Business Review, author Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic noted the following about a recent study by Yoon Jik Cho and James Perry:

“The results showed that employee engagement levels were three times more strongly related to intrinsic than extrinsic motives, but that both motives tend to cancel each other out. In other words, when employees have little interest in external rewards, their intrinsic motivation has a substantial positive effect on their engagement levels. However, when employees are focused on external rewards, the effects of intrinsic motives on engagement are significantly diminished. This means that employees who are intrinsically motivated are three times more engaged than employees who are extrinsically motivated (such as by money). Quite simply, you’re more likely to like your job if you focus on the work itself, and less likely to enjoy it if you’re focused on money.”¹

In his research on employee motivation, engagement, and satisfaction, Frederick Herzberg differentiated between satisfiers and dissatisfiers.² Satisfiers included achievement, recognition, the work itself, responsibility, advancement, and growth — but not compensation. Notice how closely this list aligns with the intrinsic motivations of play, purpose, and potential. Herzberg placed compensation on the dissatisfiers list which includes company policies, supervision, relationship with supervisor and peers, working conditions, salary, status, and security.

Herzberg’s unique insight was to distinguish satisfaction and dissatisfaction as separate from each other, but not opposites. As to compensation, the optimal result can never be “satisfaction.” Compensation doesn’t impact job satisfaction. The optimal result can only be “no dissatisfaction.”

An employee will evaluate compensation against two subjective principles: equal treatment and value differentiation. Does my salary match the market for my role? Are other people in similar roles in this company paid similarly to me? These are questions of equal treatment. Separately, there are questions of value differentiation. Have I been given a role and status in the company consistent with my talent and potential? Am I paid consistent with the unique value I deliver? The result of this self-assessment is either dissatisfied or not dissatisfied.

So if you want focused, engaged employees, you must nurture intrinsic motivation — and ensure nothing in your compensation system impedes it. And if you don’t want your employees to be dissatisfied (which creates flight risk), you must ensure that they feel their compensation reflects both equal treatment and value differentiation.

Value

Not all employees are equal in business impact. Far from it. In Laszlo Bock’s book, Work Rules!, he shares Google’s approach to compensating superstars.³ Most companies create compensation systems that assume employee performance operates like a bell curve. But, according to Block, Google recognized that the distribution of employee business impact is not a bell curve — it’s a power law. The reality is that a small number of employees deliver business impact orders of magnitude greater than their peers.

Block explains that at Google, cash and equity compensation for such superstars aligns with their unique impact. But Google goes further. When employees accomplish major breakthroughs, Google gives gifts. Initially, these gifts consisted of large stock grants (Founders’ Awards). But then they discovered that such gifts created a negative impact on job satisfaction. Debates emerged about how the grants should be shared within teams and about the consistency of award distribution. Because of this feedback, Google eliminated the Founder’s Awards and switched to giving gifts that are experiential and shared publicly, such as trips, gadgets, and elegant dinners. The point is that Google takes pains to uniquely compensate, reward, and recognize their most elite superstars — small in number but large in business impact.

Incentive-Based Pay

Incentives are tricky. A meta-analysis of 128 controlled experiments by Edward Deci and colleagues found that incentives can have an adverse impact on intrinsic motivation.⁴ In fact, results showed that the more enjoyable the underlying task, the more incentives reduced intrinsic motivation. The only positive effect of incentives on motivation occurred with tasks that are inherently unsatisfying — for these tasks, incentives can increase motivation. Based on Deci’s work, we can conclude that incentives are of most help in motivating employees who are not sufficiently intrinsically motivated by the inherent nature of the work. The more that the focus is on the incentive, the lower the intrinsic joy of the job.

However, research by Chidiebere Ogbonnaya and colleagues published in the Harvard Business Review found that certain incentives — such as performance-based pay — have a positive impact on motivational factors including job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and trust in management no matter what the nature of the work.⁵ These results suggest that motivational impacts depend of the type of incentive scheme employed, and their context. For example, Ogbonnaya’s research concludes that profit sharing negatively impacts organizational commitment and trust in management unless a large proportion of the workforce participates. In general, group-based incentives are more likely to be seen negatively than individual incentives.

For certain types of jobs — certainly jobs in sales — incentives are expected. They touch on both equal treatment (market benchmarks include incentive-based compensation) and value differentiation (incentives provide a way to fully reward the best performers for the value they create). So despite a small risk to intrinsic motivation, incentives may be critical to attract and retain top performers in particular jobs.

The key is to build incentive programs that reward the right behaviors. Here are some principles to consider:

- Always ensure incentives are market-based

- Tightly define the outcomes that drive incentive payments

- Make sure at-risk payouts align with the math of the business

- If success is unpredictable, keep the percent of at-risk pay low; if predictable, the at-risk percent may be higher

- Set targets that most people will achieve

- Concentrate incentives on individual, not group performance

- Pay high for breakthroughs, and low for maintenance

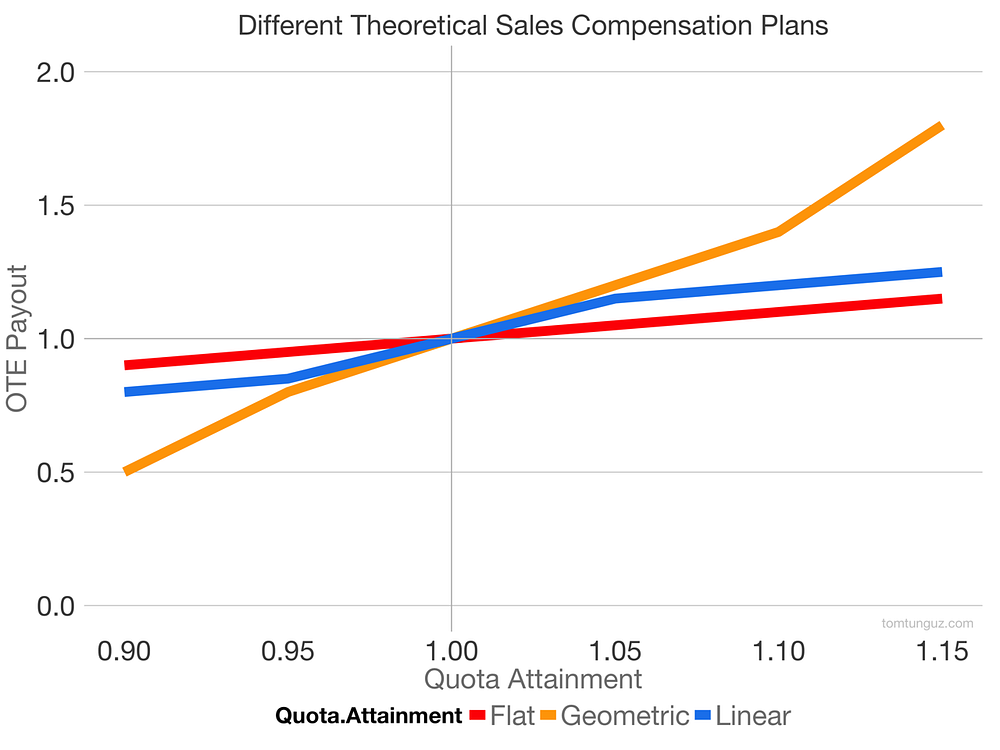

A critical choice in incentive design is the degree of performance leverage to introduce into the plan. The graph below from Tomasz Tunguz, a Partner at Redpoint Ventures, illustrates three different theoretical sales compensation plans.⁶ In the geometric model (the orange line), once a salesperson meets the quota, payments accelerate rapidly.

Such a plan could make sense if you are in a land grab, and want to incentivize high-performing sales executives to overachieve their quotas. However, if the result of this is to undermine the unit economics of your business, the decision becomes management debt. It solves a short-term problem but becomes a long-term problem: your best sales executives will ferociously resist the shift back to a more gradual payment acceleration scheme.

Compensation Decision-Making

Compensation decisions occur when you hire, promote, implement a periodic pay adjustment, change vacation policy, update the health plan, alter pay by employee demand, and decide to execute a spot reward. In each of these decisions, you express three voices: directional, executional, and moral.

You set direction well when you define roles and compensation boundaries, and think through the impact of all compensation decisions. You execute well and reveal your moral voice when you compensate consistently with the principles of equal treatment and value differentiation.

A well-designed compensation system ensures:

- Transparency of compensation philosophy

- A rational correlation among title, cash compensation, and role impact, from top to bottom

- Equity distribution consistent with both role impact and company stage at entry

- Strict internal consistency and equal treatment free from gender, ethnicity or other background bias — confirmed through regular reporting

- Limited use of incentive-based pay — concentrated primarily in Sales

- Market-based pricing, leading to defined pay ranges by role

- A formal process with checks and balances to ensure compensation decisions for new hires, promotions, and periodic pay increases are consistent with the compensation philosophy

Financial capacity to pay

The capacity to pay also alters compensation decisions. In theory, the same bucket of cash could either be spent on fewer people each making more, or more people each making less. In making this decision, consider the power law: a small handful of people drive outsized performance. When the capacity to pay is a primary constraint, all things being equal, having fewer people but paying more is probably better.

Transparency

If your compensation system is market-based, internally just, and aligned with best practice research, transparency is not to be feared. Transparency is dangerous only when you have unjustifiable discontinuities. In these situations, employees correlate a lack of transparency with unfairness and will deny secretive companies their trust.

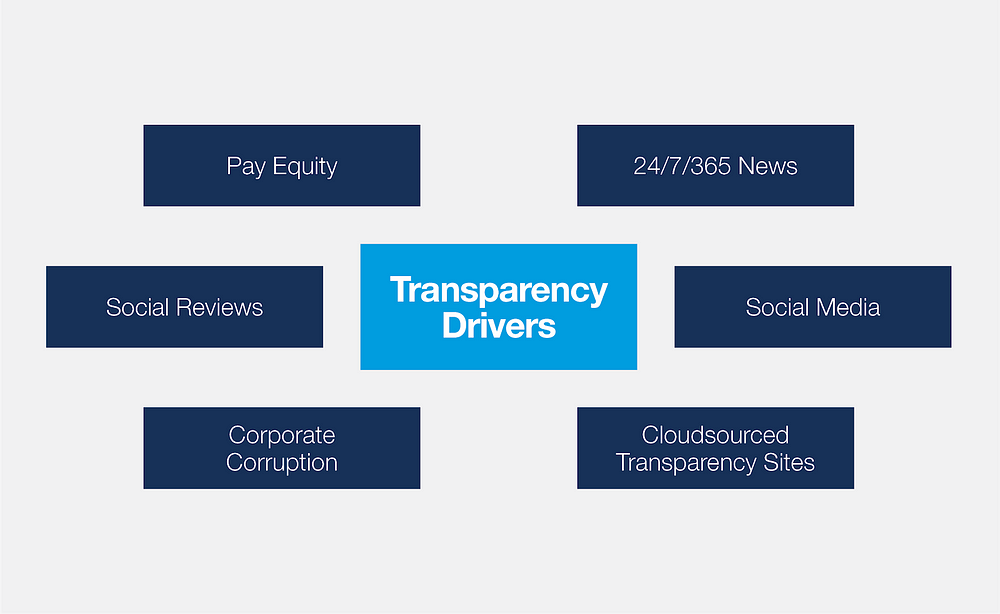

The reality is that a high-secrecy approach to compensation just doesn’t work anymore. We live in a socially connected world and this reality, among others, drives the necessity for transparency (see image, below). For example, sites like Glassdoor.com will tell the world what you pay, regardless of what you wish. And the research shows that when employees understand the compensation philosophy, employee engagement is higher.⁷

Transparency can lead to practical compensation system improvements. Google once engaged engineers in a work group to review compensation practices. The team received anonymized data on cash and equity compensation for all engineers in the group. The team noticed that incentive awards were determined on a percentage of base pay. So, if two engineers doing the same job at the same performance level happened to be at different levels of base pay (perhaps due to differences in how aggressively pay was negotiated at the point of initial hire), their incentive payments were different. The team saw this as unjust. From this insight, all engineers in the group received an adjustment to pay incentives based on a percentage of the group’s average base pay — resulting in the same incentive payment amount to any engineer for equivalent performance.⁸

Transparency is a continuum. At one end, a small number of companies, including Buffer, choose to reveal to all employees the compensation details of every individual in the company, by name.⁹ Be careful — research indicates this level of transparency may damage employee engagement. But the other end of the continuum — the “black box” approach — is much worse. Employees expect transparency regarding the following: pay ranges; decision criteria for each role; and the philosophy that guides titling, pay increases, equity grants, gifts, and other components of your compensation system.

Granting equity

Impact and risk are the two key factors that govern equity grants in a tech company. In the beginning, three founders might have zero cash in the business, but they might share big equity stakes (say, 50% for the CEO, and 25% for each of the two other co-founders). Once investors join in, they lay claim to a significant minority or (usually) majority of outstanding shares — leaving a smaller slice of the overall pie to founders and employees. As the company scales and its risk profile declines, the equity granted to any given role steadily drops. This is so despite the fact that the strike price on that equity should be going steadily up causing there to be a “squeeze play” regarding an employee’s ultimate equity exit value.

Similarly, equity grants decline sharply as you move from leadership positions to individual contributor roles. For example, if a non-founding, new CEO of a $8M revenue SaaS startup receives an equity grant representing 6% of outstanding shares, you might expect a critical, newly hired VP at the same company to receive around 2%. A senior director might be brought in at 0.75%. A director might come in at 0.25%, a manager at 0.08%, and individual contributor employees at 0.005%. Grants tend to be “four-year vesting/one year cliff.” This means that the grant does not vest at all until completion of the first year, and then vesting occurs pro rata over the remaining thirty-six months.

Often, the startup growth path is ragged. There are “down rounds” and recapitalizations. Common shares may get crushed by low valuations, reducing percentage holdings and introducing liquidation preferences that must be met before common is “in the money.” These factors also impact the exit value of employee options.

If you have a transparent culture, you will educate new hires and employees on these facts. Too often, it is only when employees choose to leave that they discover they must exercise their options within three months — often requiring a significant cash payment to the company. Or they find the exit price was under the liquidation preferences, and their options are worthless. In a high-trust, transparent culture, you are straightforward about these risks and realities in advance.

Formal process, regular checks

Because compensation is usually decided through negotiation, there is a great risk that a carefully designed compensation system will fall victim to expedient decisions. To recruit an essential new hire, you may agree to a cash and equity compensation above the established pay range, out of sync with peers. Title inflation may creep into the culture. Louder, more aggressive employees may win more substantial pay increases than less aggressive employees. Such decisions create management debt and indicate moral failures.

A formal process for approving compensation decisions helps to avoid such risks. At Google, compensation (and hiring) decisions are made by a committee, and the hiring manager is not directly involved.¹⁰ More generally, it is best practice for compensation decisions (title, equity, and cash) to have independent formal review before approval. Beware of vesting hiring managers with too much power for these decisions: they are most at risk of choosing the expedient path.

Periodic audits also make sense. Unintended bias (race, gender, age, orientation, or otherwise) can easily slip in like a software bug. It’s critical to detect these bugs quickly, so that you can fix them. The fairness and internal consistency of a company’s compensation system is a reliable indicator of the moral voice of CEO leadership.

. . .

As winter turned into spring, green shoots emerged. Bill’s efforts to win back customer trust were heroic. The moment the platform went down, he jumped into action confronting a massive spike in churn. Every customer received a one-on-one call. Within a month, Bill initiated a weekly email update to all customers to communicate progress on security steps. He chartered a Customer Reassurance Team to develop more long-term recommendations. He described the steady improvement in SparkAction CRM’s security status with transparency and specificity.

The return began as a trickle.

About six weeks after the outage, a handful of canceled dealers reached out, asking to return. These dealers longed to regain the capacity to respond with initial price quotes and to manage a transparent, consumer-centric communications process with their sales and service customers.

Soon, the trickle became a stream. Sensing opportunity, Bill and Victor co-developed a communications plan for recently canceled dealers. The “We’ve Missed You” campaign rolled out to surprising effect. Of the fifty stores that withdrew in the wake of the system outage, thirty-five returned by May.

Meanwhile, Victor and Serena worked hard to reboot the sales effort. With a smaller sales staff, marketing needed to generate quality leads. Email and digital marketing campaigns developed that addressed the security question head-on, while extolling the promises of the SparkAction CRM brand. Serena arranged for Joe to be a featured convention speaker at the National Auto Dealer Association. In front of 1,000 dealers, he shared lessons from the system hack, what SparkLight did to address it, and why all dealer technology vendors needed to learn from the experience. At the booth, dealers had many sharp questions. But SparkLight Digital finished the conference with forty-five new contracts in hand.

The product and engineering teams got back to the original product road map after executing the last significant steps to shore up security. The teams lost six months, but order finally returned.

With all other executives hard at work on the business recovery plan, you turn your attention to the funding problem. Just in time, there’s traction — which means there’s a traction story. But cash is tight, and you’re not sure you have time to find new VCs. You might be looking at an inside round.

The funding round can’t happen too soon. You are concerned about employee retention. The pay cuts you implemented put fifteen people well below their market pay level. And based on your analysis of all company positions, they are not alone. Many job roles are out of sync with the market. You decide it’s time to develop a full set of compensation ranges for all roles in the company. When the money comes in, you’ll use these guidelines to update pay for all employees.

Furthermore, you plan to share these ranges and the philosophy behind them to everyone. The days of shoot-from-the-hip compensation decisions are over. The compensation system must be principles-based and transparent to be consistent with SparkLight Digital culture. That’s the SparkLight Digital Way.

Once the money comes in.

. . .

Please visit us at CEOQuest.com to see how we are helping tech founders and CEOs of startups and growth-stage companies achieve $10m+ exit valuation.

. . .

Notes:

- Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, “Does Money Really Affect Motivation? A Review of the Research,” Harvard Business Review, April 10, 2013, https://www.rug.nl/gmw/psychology/research/onderzoek_summerschool/firststep/content/papers/4.4.pdf.

- Frederick Herzberg, “One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?” Harvard Business Review, January 2003, https://hbr.org/2003/01/one-more-time-how-do-you-motivate-employees.

- Laszlo Bock, Work Rules!: Insights from Inside Google That Will Transform How You Live and Lead, (n.p.: Twelve, April 7, 2015).

- Edward L. Deci, Richard Koestner, and Richard M. Ryan, “A Meta-Analytic Review of Experiments Examining the Effects of Extrinsic Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation,” Psychological Bulletin 125, no. 6, (1999): 627, https://www.rug.nl/gmw/psychology/research/onderzoek_summerschool/firststep/content/papers/4.4.pdf.

- Chidiebere Ogbonnaya, Kevin Daniels, and Karina Nielsen, “Research: How Incentive Pay Affects Employee Engagement, Satisfaction, and Trust,” Harvard Business Review, March 15, 2017, https://hbr.org/2017/03/research-how-incentive-pay-affects-employee-engagement-satisfaction-and-trust.

- Tomasz Tunguz, “The Theory and Data Underpinning Sales Commission Plans,” tomtunguz.com (blog), http://tomtunguz.com/theory-data-sales-commission-plans/.

- “Research from Salary.com Finds Improved Compensation Communications Drive Employee Engagement,” CompAnalyst.com (blog), November 15, 2016, https://www.companalyst.com/news-and-events/research-salary-com-finds-improved-compensation-communications-drive-employee-engagement/.

- Block, Work Rules!.

- Joel and Leo, Buffer Co-founders, “Introducing the New Buffer Salary Formula, Calculate-Your-Salary App and The Whole Team’s New Salaries,” open.buffer.com, November 24th, 2015, https://open.buffer.com/transparent-salaries/.

- Block, Work Rules!.