Tien Tzuo grew up in Brooklyn, New York. Early on, he showed a penchant for bold ideas and entrepreneurial ventures. So it was perhaps not surprising that after graduating from Stanford’s MBA program in 1998, he became the eleventh employee at an early stage startup. He chose well. The startup’s name was Salesforce.

At Salesforce, Tzuo quickly rose to become its chief marketing officer, and then its chief operating officer. From this perch, he witnessed the birth of a brand new business model: “software as a service.” Unlike the classic software licensing model, Salesforce’s software was delivered on the cloud, and presented to the customer as a service. It freed customers from big purchases of new hardware and complex on-premise installations. The whole business relationship was different. Instead of a one-time licensing fee in which the customer purchased the right to use the software, Salesforce sold its software as a service inside a subscription-based pricing model.

His position in Salesforce also gave him visibility into its scaling problems. A big impediment to growth was its financial and accounting infrastructure. Quoting and billing a subscription-based offering required workflows and technical systems that existing third-party financial and accounting tools couldn’t support. Management was beginning to realize they would need to build a homegrown solution, stealing product and engineering resources away from other (more customer-facing) development priorities.

One day in 2007, Marc Benioff was holding a meeting with two engineers from WebEx (K.V. Rao and Cheng Zou). It turns out they had been working on a similar billing and accounting problem. Part way through, Benioff asked Tzuo to join the meeting. Zou from WebEx began elaborating on the size of the problem. “We have a team of forty to fifty people on it,” he said. Benioff acknowledged the same was going on at Salesforce. On the way out of the meeting Rao said, “Gosh. If Salesforce and WebEx are both having this problem, maybe this is a good business to start¹.”

That chance meeting was the spark that ignited Zuora. With Benioff’s blessing, Tzuo soon peeled away to work with these same two WebEx engineers on building the new company. The company’s name was derived from bits of the last names of the three co-founders — Tzuo, Rao and Zou. Zuora was founded to build a cloud-based billings platform that could serve subscription-based businesses.

As CEO of the new company, Tzuo sensed that the rise of cloud computing would make the subscription-based business model the dominant means by which software was sold. But he also sensed something bigger: the business model wasn’t limited to software. Any industry might benefit from a shift towards subscription pricing.

Newspapers were subscription based. Why not retailers, health care providers, tractor companies, automobile companies and airlines? Why not razors? The subscription-based business model has many benefits. On average, it retains customers longer. When you buy something every two or three months or years, you are making a whole new purchase decision. But when you renew a subscription, you’re just continuing what you already have.

And for the subscription-based company, a recurring revenue model delivers the kind of revenue stability and sustainable growth that investors love. In the period from January 2012 to December 2018, subscription-based companies tracked by Zuora grew revenue an average of 18.1%, per year, compared to the average S&P 500 company, for which revenues grew 3.6%. Subscription-based business models beat the baseline by a factor of five².

It wasn’t long before Tzuo had coined a phrase that has since become synonymous with Tzuo and his company: “The Subscription Economy.” In that three-word phrase, he succeeded in naming a large and fast-growing new category (subscription-based businesses) — a category his company was uniquely positioned to serve.

With the category defined, Tzuo embarked on a thought leadership campaign to evangelize the “Subscription Economy” idea. The campaign was and is so varied, multi-dimensional and relentless it brings to mind the Eveready Bunny (“it keeps going and going and going”). Years later, these efforts have paid off. Zuora is a well known global brand in no small part because of the success of the “Subscription Economy” campaign. It’s hard to think of any company CEO in the world today who has done a more effective job of enterprise thought leadership than Tzuo.

Of course, every step on the journey of company building at Zuora has been hard won. The product has come together, piece by piece, by translating market and customer needs into wave after wave of product development work. And on the revenue engine side, as the company has scaled Tzuo and his team have refactored the customer segmentation scheme ever more granularly so as to serve pockets of opportunity with greater precision.

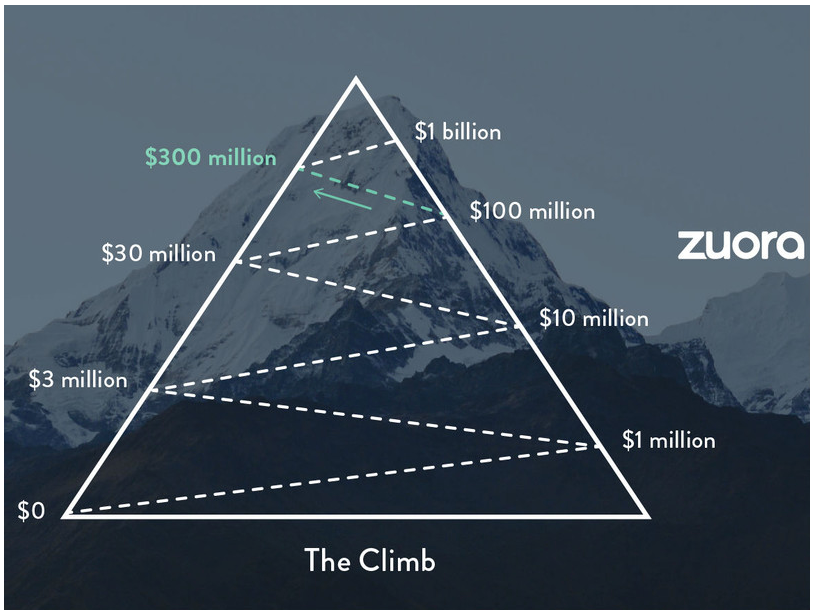

Tzuo described this company building journey in a presentation to Index Ventures back in 2015. He made the case that the type of leadership it takes to get from $0 in revenue to $1M in revenue is fundamentally different than what’s needed from $1M to $3M, or $3M to $10M, or beyond. The first step is to prove the idea. Then you need to prove the product. Then you need to prove the market, then prove the business model, then prove the vision, then prove the industry. Each “proof” step requires a unique approach to leadership. Each stage requires a pivot, much as a climber will zig and zag up the mountain from switchback to switchback.

The story of Zuora is a zig zag journey towards the top. On April 12, 2018 Zuora was listed on the NYSE under the symbol ZUO. It was valued at $1.4B on opening day. Today, a little over a year after going public, Zuora continues its journey of company building. The ride has been bumpy, but Zuora continues to grow in a massive category. Tzuo has put focus on key initiatives to drive long term growth. The company’s future is bright.

Let’s consider how the eight core ideas in this book relate to Zuora:

1. In the face of continuous change, the fit systems enterprise relentlessly pursues a customer centric, world-improving Virtuous Vision

I must first disclose that Tien Tzuo is a friend. I have had the privilege to meet with him at various points over a ten year period on his company building journey, all the way from the company’s early days (2009) on past its 2018 IPO. These periodic meetings have given me a bird’s eye view into his approach to leadership at various stages of company growth. I’ve seen how he has traversed the growth journey, overcoming challenges along the way.

Since the beginning, Tien Tzuo has exhibited a deep commitment to his customers. The company was barely two years old when at my own startup, then called ResponseLogix, we adopted Zuora as our billing solution. We were a B2B SaaS business facing all kinds of billing challenges, and needed Zuora to help us fix the problem. Right after we signed up, I received a call from Tien. He wanted to get together, to thank me for my business and to find out how the implementation went. I actually was super busy at the time, and didn’t immediately take him up on his offer to meet. He emailed me three times in search of a time for us to get together.

That was impressive to me, because at that point in time, we weren’t a very large Zuora customer. In fact we were probably one of their smallest. Nonetheless, Tzuo wanted to meet me, thank me and learn from my experiences with his product. That’s customer centricity.

I met Tien again in 2013, when I launched CEO Quest (where we provide advisory support to tech company CEOs). I was seeking to refine the core concepts that would guide my approach to CEO coaching. I talked with him about the various company building domains — product development, revenue engine development, systems development and people development — and the importance of funding. At one point he said to me, “Hey wait a minute. Where’s the customer in your framework?” For Tien, the customer is always front and center.

On one of my visits, Tien walked me around Zuora’s Foster City office — which was rapidly expanding. We were talking about how to achieve organizational alignment at scale across the critical dimensions of vision, mission, values and strategy. He stopped and turned to a worker sitting at a desk nearby. “Can you show our visitor your Zuora card?” This young sales development representative proudly pulled out a laminated card that showed the company’s vision statement, mission statement, core values and four strategic imperatives. When asked, the young man was able to state the company’s core values without looking at the card. “That’s how you maintain alignment,” Tien said.

Zuora’s vision statement is “to enable businesses around the world to launch and monetize any subscription products and services.” It is a customer centric, virtuous vision.

2. To do this, the enterprise must advance two imperatives: to be Generative, and to be Adaptive. Being generative (continuously creating new value) is always the first priority; being adaptive (increasing resilience, scalability and efficiency) is second

Solving market and customer problems is a generative act. At Zuora, its product line evolved from a billing solution into a comprehensive suite of subscription-related services by identifying and addressing customer needs one feature at a time.

The Zuora product line starts with Zuora Central (which keeps track of subscription payments, billing, collections, pricing, product catalogs and accounting). But there other product lines as well. These include Zuora Billing, for recurring billing operations; Zuora RevPro, for revenue automation; Zuora CPQ, for sales quoting; Zuora Collect, for payments; and Subscription Order Management, for renewals and complex deal management. Zuora also has developed an app marketplace called Zuora Connect, allowing partners to develop and list apps that can sit on the Zuora Central platform. Together, these create a rich array of revenue engine and accounting system solutions for subscription-based businesses.

In revenue engine design, Zuora has had to balance differences in verticals, business size and regions. Tzuo’s sales organization has gone through multiple reorganizations as it has scaled, creating ever-more targeted sales domains to maintain sales focus at scale. Company infrastructure has needed to keep up with business growth. And along the way, product managers and engineers have had to build a growing array of applications.

Resilience is accomplished when teams throughout the enterprise are responsible for clearly defined domains in which they can “do one thing and one thing well,” and in which they have feedback loops available to them to understand their current state and the progress they are making. Particularly as it pertains to its revenue engine, Zuora has built a highly accountable, data driven, domain-based organization.

Scalability is accomplished when obstacles to growth are removed. A key challenge for any fast scaling technology company is its technical systems. As a startup scampers up the ragged scaling path, it’s hard to devote any time to refactoring technical systems. The need to get the next product feature out the door is too pressing. Over time, the result is a technical monolith — which can become an ever-increasing drag on growth. Tzuo is well aware of that risk. In 2015 he brought in new technical leaders charged with the responsibility to attack the monolith and refactor it into a microservices architecture, component by component. This was an important adaptive act. For all too many CEOs, it is one that is all too easy to ignore or delay. Not Tzuo.

3. When conceiving of the enterprise, the Systems View is primary; the functional view must be secondary

To scale a company successfully, you must be able to perceive the integrated nature of things. What you do now will influence what you can do in the near term and the long term. Actions you take in one part of the business will impact other parts of the business. The way you build technology will impact how you can organize people and workflows down the road. Attacking symptoms without attacking root causes may provide incremental short term benefits, but are sure to cause long term problems. Systems tend to exhibit dynamics such as these. The leader who wants to build a fit systems enterprise must view the enterprise as a system, comprised of subsystems and domains. The leader who is a systems thinker interacts carefully with the socio-technical systems inside the enterprise.

Evidence of a systems view at the top can be seen in Zuora’s approach to refactoring its technical systems. Early on, Tzuo recognized the need to shift the company’s technical systems into a more modular, microservices based architecture. In 2015 he brought in Brent Cromley, SVP Technology at Zuora, and Henning Schmiedehausen, Chief Architect, to lead the transformation initiative. These leaders worked with other executives such as Tiago Nodari, lead product architect, to mobilize a domain driven design approach to the problem.

It took time to build shared commitment to the refactoring initiative. The pressure to continue to innovate is strong; a refactoring project sucks up resources that could otherwise be used for new innovation initiatives. But from Tzuo on down, the project was given the air cover it needed to take hold. Today, in Cromley’s estimate, the recode is about ⅓ done. But because the pace of change has steadily increased, he believes the overall digital transformation is now more than half done. He expects the refactoring to be largely complete within two years. There is now a broad recognition across all technical teams that the short term pain of refactoring will be rewarded with long term scalability and systems resilience.

That’s an example of the payoff that comes from leaders who hold a systems view of the enterprise.

4. The enterprise is comprised of Operating Systems (such as the revenue engine system and the product management system) that create results; and Meta Systems (such as the governance system and culture system) that exist to elevate the performance of operating systems

One of Zuora’s most effective operating systems — measured by results — is its cash management system. Zuora was founded in 2007. By the end of that year, the company had raised an A round — a $6M funding event. Less than a year later, it raised a $15M series B. Two years after that, it raised another $20M in a Series C, and then another $36M just a year after that. A $50M Series E round followed in September of 2013, followed by a $115M Series F less than two years later, in 2015. The company’s 2018 IPO generated for the company another $150M in funding — an impressive $400M in funding in just 12 years.

Zuora’s funding success speaks to the visionary leadership of its CEO, Tien Tzuo. Investors buy stories. A winning story has just the right mix of “opportunity” (potential for future growth) and “traction” (proof of past and current growth), told with vision and conviction. Tzuo is a world class storyteller, as the record shows. And he delivers on his promises.

The other operating systems, such as the product management system and the revenue engine system, are all steadily maturing. These have been uplifted by Tzuo’s focus on its meta systems (governance, strategy / planning / architecture, culture, DataOps and engineering).

As to culture, Tzuo has devoted himself to socializing company values at scale. He instituted the “Z-Awesome” award, given each quarter to the employee who most exemplifies company values (as nominated by peers). He has allocated money to make work fun, such as throwing celebrations for various holidays such as Chinese New Year, Diwali and Valentine’s Day. He has worked hard to hire diverse candidates. He has launched Z-Leadership workshops to support career growth.

In April 2019 it was announced that for the second year in a row Silicon Valley Business Journal had named Zuora on of the best Bay Area companies to work for³. One of the responses from the Business Journal’s employee survey read: “Our CEO is a visionary who also cares about the people. He knows people’s names and he knows what they do. He is the person driving the actions to do more for our people, and he holds his exec team accountable for doing the same.”

5. The fit systems enterprise features Domain Driven Design — both in its technology design and in its organizational design. All systems in the enterprise are made up of domains; these domains integrate people, workflows, technology and money flows to achieve business outcome objectives.

The digital transformation initiative at Zuora is anchored in domain driven design. The first job the technical leadership team took on was to define every domain in the business that required technical systems support. They needed to expose the tightly coupled dependencies that already existed in the company’s current technical systems — especially those that crossed domains.

Given the nature of Zuora’s product, customers consider Zuora mission critical infrastructure. This fact required the technical teams to address existing customer integrations with extreme care. The team has had to figure out how to refactor into microservices while still ensuring 100% backward compatibility. That’s a complex technical problem.

Domain driven design does not just apply to technical systems. It is relevant to the organization design of the entire enterprise. At Zuora, domain driven design principles are exhibited in its revenue engine design. Sales teams are broken out by company size, region and verticals. Marketing, sales development and account executive sales functions collaborate to achieve business outcome objectives inside these domains.

6. In the fit systems enterprise, data access is democratized; there are Feedback Loops Everywhere

At Zuora, OKRs and KPIs cascade from the executive level on down to every team and individual in the enterprise. Dashboards proliferate, providing real-time performance tracking. Zuora is a data driven company. It’s a top priority to ensure every team throughout the company has access to the data it needs to do its job.

7. The fit systems enterprise exhibits rising Digital Leverage: its systems are built via reactive microservices architecture; its data infrastructure is modern and cloud-based; and its technical domain teams pursue disciplined agile delivery methods to build powerful solutions

When Cromley and Schmiedehausen joined Zuora three and a half years ago, they were given the job to transform Zuora’s technical systems into a modern microservices architecture. Today the transformation to microservices architecture is half done, and the entire technical organization is mobilized to finish the job. But it wasn’t always that way.

Cromley’s first job was to build alignment amongst key technical leaders that the mission to refactor the monolith was the right choice for Zuora. In an August 2017 article posted on InformationWeek.com, Cromley made the case for change:

“Technology companies are at such a moment of inflection now. Even as they have invested in monolithic applications, they have had to shoulder the limitations imposed by the size of their code and their inability to handle independent scaling. Many now understand that they will need to transition from a monolithic application to a microservices architecture in order to better position themselves for future growth and product development. A microservices architecture offers greater global accessibility and enhanced functionality for customers. It makes it possible to iterate new features and improvements as they naturally occur and creates a flexible platform for the integration of future products and features⁴.”

With microservices, you have to start with the business: what are the natural domains, and how can they be more cleanly separated with fewer dependencies? You must define domain boundaries — the bounded context — and identify the transformations that must occur inside each domain.

Cromley argued that microservices architecture enables engineers to innovate on a service as required without worrying about the impact on other adjacent services. This increases the speed of innovation, and reduces the cost of mistakes. In the same article, he continued:

“Transforming to a microservices architecture requires a transformation across all disciplines: engineering, QA, program management, operations and product management, as well as customer support. It will not be easy work, but a shift to a microservices architecture will provide ancillary benefits well beyond primary goals because it brings consumer-level scale and architecture into the enterprise and makes it easier to take advantage of changes in the computing and technology landscape. It also allows each microservices product team to act as a mini-startup company within the organization that owns its own destiny, innovates at the speed of its brightest minds and maps its own journey…⁵”

Cromley admits that he had to overcome some organizational resistance. No one disagreed with the theory that a shift to microservices would eventually be required, but there were disagreements about priority, the level of resource commitment and pace. For some, it took time to embrace the required role changes. Microservices architecture changes how you organize people. This affects how you lead, and it changes the role of engineers and product managers. It’s not just a technical shift — it’s an organizational and cultural shift.

With microservices, authority relationships are realigned. You can’t operate in functional silos. For instance, the “all knowing senior engineer” who has been at the company since forever and knows every dependency in the monolith becomes less mission critical when technical systems have been refactored into microservices.

Henning Schmiedehausen, Zuora’s chief architect, emphasizes that in digital transformation, everything is a tradeoff. You need to design a system made up of loosely coupled services, but you also need to make sure the overall system works reliably. You want to build for the future, but you need to be backward compatible with the past. For Zuora’s customers, billing is critical. You have to execute the surgery with precision. Schmiedehausen emphasized that the shift to microservices must be executed with deep understanding of the pragmatic tradeoffs involved. It’s a pragmatic and purpose-driven technical conversion, not a religious conversion.

Schmiedehausen goes on to argue that domain driven design isn’t just about defining the business boundaries of a domain. You also have to define its data boundaries. Even more, you have to identify the dependencies between domains. Then you need to establish a contract between domains that defines how information will be shared between them. Then you need to build asynchronous APIs that fulfill the contract. All of this requires more than just human alignment. It also requires an array of tools — such as for continuous integration, continuous delivery, deployment, metrics, monitoring auditing and more.

As the transformation initiative has progressed, the Zuora’s technical capabilities have kept pace. Now the company is exploring how to leverage AI and other solutions requiring cloud-based fast data capabilities. That’s the power of digital leverage.

8. The fit systems enterprise exhibits a key foundational asset: “In The Loop Leaders”. They are ethically grounded, digitally literate systems thinkers. These leaders focus most of their attention on advancing a virtuous vision, improving the meta systems, ensuring domain team autonomy and increasing the density of 10Xers in high variation domains

Tzuo has spoken honestly about his own lessons of leadership along the company building journey. A few years after starting Zuora, he decided to bring in an organizational psychologist to conduct a 360 degree review with his direct reports. The review was eye opening. He learned that he was perceived by many to be an intense but remote leader. A tool-based assessment exercise revealed that he ranked high as a visionary evangelist, but low as a relationship builder.

This insight led Tzuo to make some changes. He began to work harder at his coaching role. He began to seek ways to recognize the achievements of others. His response to feedback exhibited two key hallmarks of an In The Loop leader: self-awareness and the ability to self-improve. Once a quarter, Tzuo holds a retreat for the executive team. And he invites his extended management team out to dinner once a week. These direct connections keep him close to the action, and strengthen the bonds between himself and his team.

Tzuo’s commitment to continuous product innovation is obvious, revealed in the company’s steady stream of product enhancements. Less obvious is his work under the hood. His own systems thinking approach has led to the maturation of all Zuora operating systems. Specifically, his hand can be seen in the maturity of the product management, product discovery, revenue engine and cash management systems. So too with all the meta systems: governance, strategy / planning / architecture, culture, DataOps and Engineering. His own digital literacy is proven in his commitment to digital transformation — the move to microservices.

Zuora is where it is today because Tien Tzuo is an In The Loop leader: an ethically grounded, digitally literate systems thinker.

Summary

Zuora has been a public company for just over a year. It didn’t even exist thirteen years ago. Since its inception, Tien Tzuo has led his company on a climb up the company building mountain, one switchback at a time. Like any company, the scaling path has not been easy. The journey of the fit systems enterprise is never over. This is as true for Zuora as it is for any other company. But when you consider, over the course of its existence, the emergence, growth and current dominance of Zuora’s thought leadership position — the degree to which Zuora has emphasized creating new product value — the intelligence with which it has scaled its revenue engine — and its commitment to transform its technical systems into a modern microservices architecture — it’s not to call Zuora a fit systems enterprise.

Notes

- Tzuo, Tien. Subscribed: Why the Subscription Model Will Be Your Company’s Future — and What to Do About It. New York, NY: Penguin Random House, 2018.

- Zuora. “The Subscription Economy Index Report.” The Subscription Economy Index Report, 2019.

- “Zuora Does It Again: Best Place to Work.” Zuora, April 25, 2019. https://www.zuora.com/2019/04/25/zuora-best-place-work/.

- “Why I Gave My Engineering Team a Chance for a Do-Over.” InformationWeek, August 22, 2017. https://www.informationweek.com/devops/why-i-gave-my-engineering-team-a-chance-for-a-do-over/a/d-id/1329686.

- Ibid.

To view all chapters go here.

If you would like more CEO insights into scaling your revenue engine and building a high-growth tech company, please visit us at CEOQuest.com, and follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter, and YouTube.