From company inception until at least Minimum Viable Traction, there’s only one right way to fundraise. The moment you close a funding round, give yourself that much-needed four-day weekend to rest and recuperate. Then, on your first day back to work, start planning your next funding round.

This approach is all too rare. The biggest funding mistake made by early stage company CEOs is to think of funding as an inconvenient, disruptive necessity — one that impinges upon your primary work priority, which is the product and the revenue engine. CEOs of this mindset will try to cut funding corners. They will delay until cash is short, then rush the process, resulting in sloppy execution, loss of negotiation leverage, and existential risk.

Make time your friend. Begin at least six months ahead of your cash-out date. This will give you the time to do it properly.

Here are the steps from inception to term sheet:

- Identify the value inflection point you must next achieve to be fundable and mobilize the entire company towards achieving it

- Determine your funding objectives

- Create your funding team

- Select lead investor prospects

- Understand the investor mindset

- Define your traction story

- Define your opportunity story

- Organize your claims

- Create your story assets

- Build the data room

- Prepare your negotiation strategy

- Practice, practice, practice

- Line up investor meetings

- Execute and learn

Plan for the Next Value Inflection Point

Shortly after you close a funding event, you must look out towards the next one. Needless to say, your next financing round will be much smoother and more successful if it is anchored by the traction of having achieved the next value inflection point.

As CEO, your job is to subordinate everything to this goal. Actions in product, revenue engine, people, and workflows must ultimately yield achievement of the next value inflection point. This is your traction story.

Achieving the next value inflection point requires two things: direction clarity and sharp execution disciplines. The “Objectives and Key Results” (OKR) planning document is a powerful tool for this purpose. It aligns key strategic objectives with specific, time based results targets. In turn, these results targets are broken into weekly tasks that are tracked to ensure steady progress is made. When reviewed weekly in an executive staff meeting, you ensure all are rowing in the same direction.

Never let the tyranny of the urgent impede the achievement of your next value inflection point.

Determine Funding Objectives

How much do you want to raise? This is a simple but important question. Never propose a range of funding (such as “we’re raising $5M — $8M in funding”). The investor will conclude that either you don’t understand your funding requirements, or you aren’t confident about your capacity to raise what you need. Neither impression is positive. Determine what it will take to reach the next value inflection point with six months of cash to spare. That’s the number. Don’t raise less, and don’t raise more: you’d only cause needless dilution. Targeting a higher amount than needed might even squeeze out an otherwise perfect VC fit if the required check size exceeds fund guidelines.

So, pick the number you need and raise that — no less, no more. And be decisive about it. “We are raising $8M in this round. We invite you to participate in this opportunity.”

Create the Funding Team

Your funding team is comprised of your VP Finance or CFO (or for early stage companies, your temp CFO), your board and / or early angel investors, and your lawyer. Your head of finance will help you build the financial projections for your business. If she is good, she will play a significant role in challenging the growth assumptions. She will model the linkage between traction history and projections, and point out any discontinuities (such as a 30% month-over-month growth in sales when there is no historical evidence that such growth is achievable).

If you have managed relationships well and your company has progressed in a positive direction, your board and early investors will be on your side. Lean on them. First, to help you create a compelling traction and opportunity story, and then to win introductions to targeted investors.

Your lawyer is a key member of the team. It is important to find a lawyer with significant experience negotiating financings at your funding stage. The more pattern recognition, the better. A good lawyer will know what terms matter most, and what points to fight hardest on. A bad lawyer will burn through many high-cost hours fighting for deal terms that don’t matter, either because he doesn’t have experience or he wants to run up the fees. The result is a damaged relationship with your investor, a big legal bill, and a higher risk the entire deal will blow up.

The time to confirm you have the right lawyer is at the beginning of your fundraise process, not at the end.

Select Lead Investor Prospects

It is an all-too-common sin to seek out investors whose investment theses are inconsistent with your company’s story. Don’t do that. Make sure that the investors you arrange to meet are stage relevant and invest in companies like yours. Some investors focus only on certain verticals. Others focus just on certain business models. Still others require geographic proximity to the companies in which they invest. To protect both your time and your investor’s time, make sure to seek out only those investors who are a fit.

If you are a private company seeking venture investment, an important factor in the selection process is to identify VCs that have a history of leading, not following. You may want to secure a round that includes multiple VCs, called a syndicate, but every syndicate has a lead investor. The lead sends you the term sheet. The lead catalyzes the round. Followers are fine — they participate, and add cash to the pile so that you achieve your funding target, but in a fundraise process, your priority is to find the lead. As you research VCs that are a fit in terms of vertical, business model, and stage, check also to determine the percentage of their portfolio companies where they have led at least one round. You need leaders more than followers.

Understand Investor Mindset

An investor’s mindset is dominated by one overriding question: “does this investment opportunity compare to all the other investment alternatives available to me, given my investment thesis?”

It’s not enough to be fundable. You must be more fundable than all other companies available to your prospective investor. For each investor, it’s a competition with only one winner (or, with larger VC firms, perhaps a handful) in any given quarter.

Not only must you make a credible case that your company will make a lot of money someday, you must go further and spin such a compelling story that your company rises and rises up the pyramid in your investor’s mind, until it has reached the pinnacle — above all the other stories that investor has recently heard.

Define Your Traction Story

As noted in Chapter 2, each value inflection point is a milestone. Investors want to see progress at every funding event. Are you stuck on the same value inflection point you were at during your previous funding event? Or have you leapfrogged forward? Momentum in your business creates momentum in your fundraising. This is true at every stage of the funding continuum, all the way to the public markets.

If you are stuck or have progressed slowly, fundraising will be much harder. You will be forced to emphasize opportunity without the credibility that comes with a traction story. There are three implications. First, your opportunity story will need to be highly compelling, specific, and credible. Second, you need to be flexible about pre-money valuation, because you are likely to face a down round. And third, the investor will seek their proof of traction and future opportunity in you, the CEO. Your resume and your presentation will be even more important if company traction is lacking.

Define Your Opportunity Story

Companies win in the marketplace because they gain competitive advantage. This may occur because of a unique insight into the psychology of the customer. Or it may be due to a technical or workflow breakthrough no one else has achieved. Or it may be because of a price advantage. Or a superior go to market execution strategy. Or because of unique access to channel partners. Or a mix of all of these.

As CEO, you have perceived these openings in the market and have built sharp plans to exploit them. Opportunity comes packed in vision and plans. Your vision and your plans are powerful only inasmuch as they exploit a latent market truth. The smart investor will scrutinize your vision and plans with much diligence, seeking to test their power. Investors understand that these plans are also Rorschach tests; they give as much insight into you as they do your company. As the investor listens to your pitch, a set of questions will be floating in their heads: is this vision rational and compelling? Are the plans logically sound and internally consistent? Has the CEO articulated them clearly and concisely? Has the CEO clearly and confidently defended how he will achieve the next investable milestone?

Never forget: you are a big part your opportunity story.

Let’s say you’re an early stage company seeking angel funding. The only traction you can show an investor is the concept you have created. By definition, at this stage most of the story is future focused — it’s an opportunity story. Your job is to explain the fissure in the market’s bedrock that you have discovered. You must show the investor how you will exploit it.

What facts and assumptions anchor your belief about that crack in the market? How extensively have you researched this opportunity? How authoritatively have you confirmed the pain point? How authoritatively have you confirmed the competitive set and your advantage? How sure are you that the prospect will buy? Can you prove it? Here’s a big secret: the best way to tell an opportunity story is to match every key point with traction evidence.

At every stage of a company, all the way through to public company status, your opportunity story will be important. It will include one or more key strategic insights (the cracks in the market). But it must also include substantiating evidence that the insights are accurate and exploitable. As you prepare your story, gather and organize these facts and assumptions. Each will be critically assessed; make sure you have validated everything. As you scale, the traction story will become more heavily weighted than the opportunity story — but both are important.

Organize your Claims

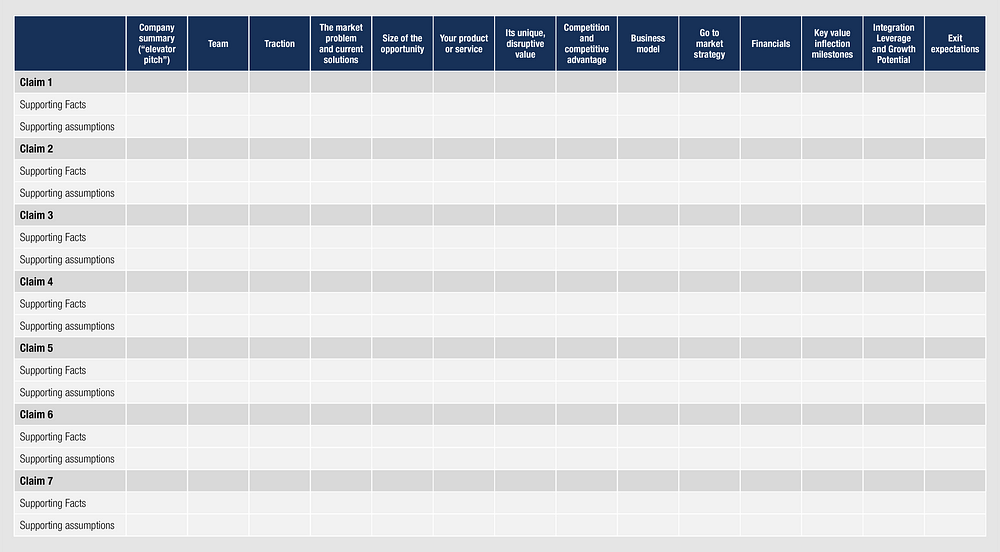

You must sell your investor the best story your facts allow. It’s helpful to inventory your claims, supporting facts, and annotated assumptions. Put them into a spreadsheet that looks something like this — your Claims Matrix:

Once you’ve entered the data, you can color code the cells “Green / Yellow / Red” — green for the strongest, most substantiated claims; red for the weakest or least substantiated parts of your argument. The Claims Matrix is a heat map of your story; the strongest and weakest components become crystal clear. As you mobilize the story for investors, you can simultaneously work on the business itself. You can attack the reds, seeking to turn them into yellows, or even greens.

Create Your Story Assets

There are six storytelling assets that must be created:

- The elevator pitch

- The executive summary

- The full spoken narrative

- The pitch deck

- The Q&A talking points

- The product demo

Leveraging your claims matrix, organize your claims in the order most likely to spark interest and create momentum. The details will vary depending on the storytelling asset, but the basic story structure remains the same.

Of course, the larger your company, the more documentation is required. For instance, later stage private companies seeking hedge fund investments may need investment bankers to prepare private placement memorandums. And of course, on the path towards IPO, the documentation requirements explode. Just remember that every document is simply story support. It’s the story that counts.

Each storytelling situation has a different purpose, requiring different assets. If you are on stage at an accelerator demo day for an eight minute pitch to 200 investors, your deck is short and your purpose is business cards. If you meet a VC at a cocktail party, your elevator pitch is brief and your purpose is a request for the executive summary. For the VC you already know, your conversation is informal and your purpose is honest feedback. For the VC you don’t know, the half-hour pitch will be deck supported and formal, and your purpose will be a follow-up meeting or full partner meeting. For a full partner team pitch, you’ll have a full deck, a product demo, Q&A talking points, and a narrative you’ve mastered; your purpose will be to move into pre-term sheet diligence.

Your storytelling assets arm you with the right tools for every presentation situation.

Build the Data Room

The state of your data room and the quality of your data will speak loudly. Depending on company stage (the further along, the more detail), the data room may include:

- The cap table

- Sales, bookings, revenue, retention history by month

- Expense history by line item by month

- Historical financial transaction detail (ideally all financial transactions, since inception, as recorded in the general ledger)

- Employment, consulting and advisory contracts

- Important non-financial metrics (visitors, number of subscribers, time on site, etc.) by month

- Sales pipeline: prospects at the top, mid and bottom funnel

- Customer and supplier agreements

- The product road map

- Competitive analysis

- Top executive biographies

- Organization chart

- Roster of all employees, with job description, and base and bonus compensation details

- All at-risk pay plans (bonus and commission plans)

- Proprietary Information and Invention Agreements signed by all employees

- Employee handbook signed by all employees

- All other policy statements, payroll and personnel practices

- Any employee or former employee disputes (wrongful termination, harassment, occupational safety, civil rights), correspondence, and documents

- Any confidentiality agreements with employees

- Documentation of tax liabilities and disputes

- Schedule of any pending legal or arbitration proceedings

- List of key regulatory compliance requirements

- Business insurance policies

- All other contracts and agreements (indemnification, leasing, licensing, real estate, government permits, data processing, channel partner, services, etc.)

- Intellectual property: schedule of patents, trademarks, service marks, copyright

- Technical diligence materials — the code base, architectural schema, documentation, testing plan, recovery plan

It could take a couple of months to gather, cleanse, and organize all the data in a data room. Make sure it’s comprehensive, and that where needed, it provides detailed validation of all of your claims.

Prepare the Negotiation Strategy

The more you have thought through all steps in the fundraise process from inception to close, the better. This allows you to be one step ahead of your investor.

There are many points of negotiation to consider along the journey, including:

- How much diligence to accept prior to a term sheet

- What pre-money valuation expectations do you have

- In return for the cash, what downside protections are you willing to provide the investor?

- What control are you willing to give the investor?

Some diligence before a term sheet is appropriate. Your investor will want to validate revenue and bookings growth, and may want to talk with some existing (and possibly former) customers. This is normal. It isn’t normal to conduct deep financial records analysis, or to look at your code base, or to explore the details of your product road map, or to hold extensive conversations with multiple members of your team. If you are asked, respectfully tell the investor that after you have received a term sheet, you are happy to provide more due diligence.

Sit down with your lawyer and go through financing terms that may crop up in a term sheet. If you can think through your position and develop a negotiating strategy regarding the most common terms before you begin investor meetings, you’ll be a more efficient and effective negotiator when the term sheet arrives. Armed with an understanding of common terms, you’ll be able to smoke out the VC who is proposing non-standard, inappropriate terms. You can walk away faster.

Practice, Practice, Practice

In his race for a second term of office, President George W. Bush came into the first presidential debate unprepared. Hit with a tough question from Jim Lehrer, he stumbled and wandered. Had there been only one presidential debate, it could have cost him the presidency. Luckily for him, in the two subsequent debates he came in much better prepared and ultimately won the day.

You don’t get three presidential debates. You only get one. So practice, practice, practice. With enough practice, you can effectively handle anything that comes your way.

Line Up Investor Meetings

It’s not enough to target the right VC firm. You need to identify the general partner or managing director with the most relevant investment background given your stage, business model, and vertical focus. Now that you have identified a target investor list of 50 or more managing directors, it’s time to secure meetings. VCs are busy people and are constantly pursued. Most VCs are selective and only take meetings when they have been approached by someone they trust. So once you have identified your targets, your next step is to identify, for each target, who you know that knows them. You must then convince this person to introduce you to the VC.

If you find yourself pointed to an associate at a VC firm, be careful. Your time is your most important asset in fundraising; it’s important to know that associates have limited clout. You can and should pitch to associates — associates can expand your reach, and you’ll only have access to so many managing directors and general partners — but make clear your goal is to meet with a managing director. An associate filters deals. Provide only as much information as is needed to secure that meeting with an MD or partner.

Execute and Learn

Every investor pitch is a learning opportunity. After each, critique yourself. Sit down in a coffee shop and write down all the points in your argument that fell flat, or were ill-supported by facts. What questions caught you off guard?

If a pitch meeting elicits a request for more information, follow up immediately. A quick turnaround on requested information provides the investor a sense that you have done it before — in other words, it’s a hot deal. After the second meeting with an investor, ask what their process is — both the steps and the timing.

If an investor doesn’t invest, be sure to ask why. This is a perfectly fair and appropriate question, and the considerate investor will answer. In all likelihood, you will pitch to dozens of investors every time you raise funding. So, be sure to squeeze lemonade out of each prospective investor, especially the ones that say no.

Assuming you are fundable, your efforts will catch traction. Even before the term sheet, you may begin to receive solid financial commitments: “We will do $1M”. Or, “We are interested in making a $500K investment, assuming we like the terms.” If you don’t yet have a lead investor, these “soft circle” commitments become momentum builders. A lead investor will be happy to know that you have “soft circled” $2.5M for your $6M round. In that example, if the lead puts in $2M, there’s only $1.5M left to find. Of course, your soft circle isn’t legally binding, but usually soft circles firm up once the lead steps forward.

If you’re lucky, multiple firms might express interest in leading the round. If that’s the case, once the first term sheet arrives in your inbox, be sure to immediately connect with the others. This will spark deal competition. If you’re in this situation, be careful how you manage information. Everything you share must be true — avoid the wild exaggeration. And be careful what you do share: you don’t want multiple VCs collaborating with each other until one of them has sent you a term sheet.

. . .

To view all chapters go here.

If you would like more CEO insights into scaling your revenue engine and building a high-growth tech company, please visit us at CEOQuest.com, and follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter, and YouTube.