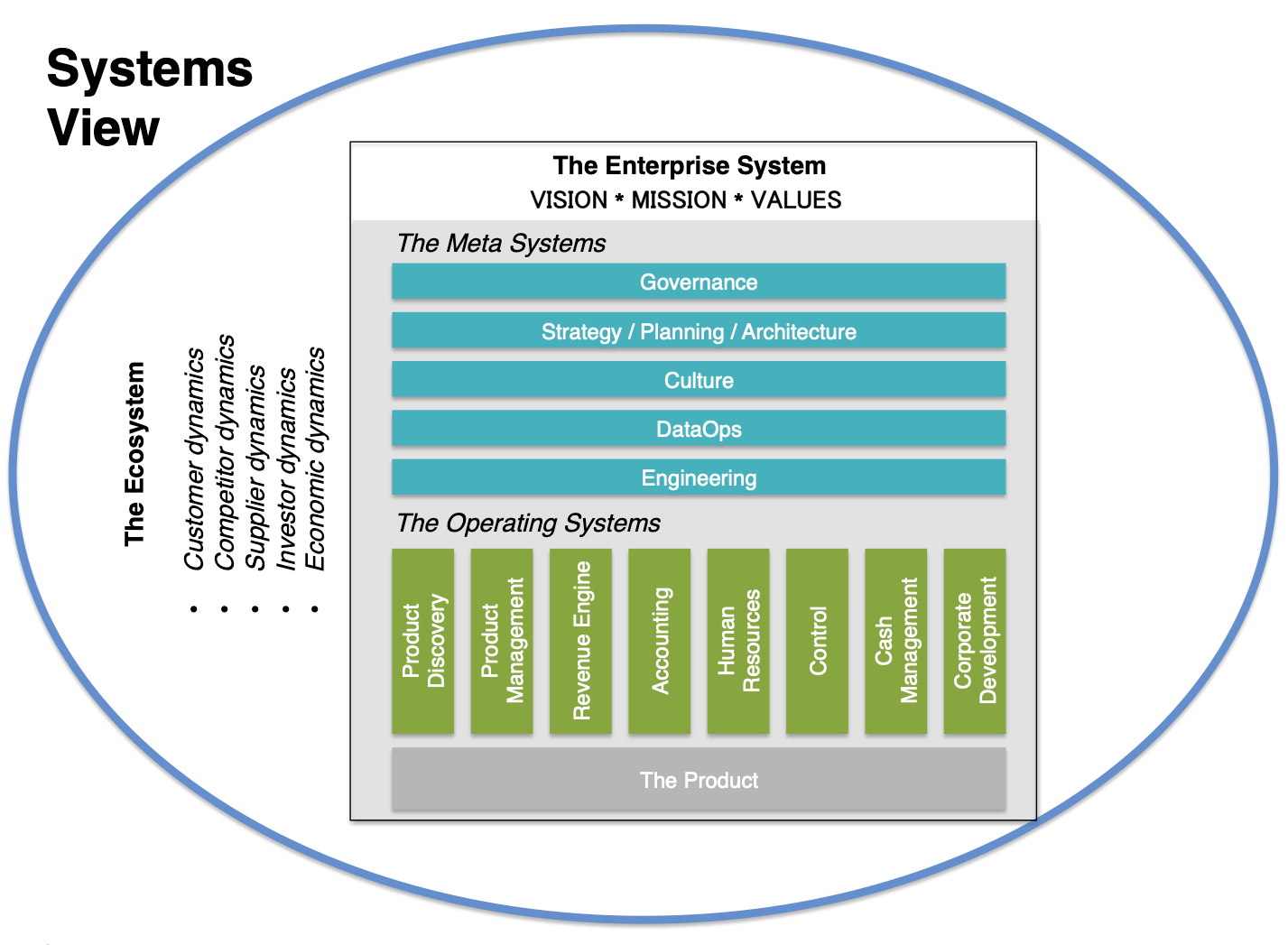

The governance system is a meta system.

A recent Googlegeist survey became a hot news topic.

“The annual internal poll, known as Googlegeist, asked workers whether (Google CEO Sundar) Pichai’s vision of what the company can achieve inspires them. In response, 78 percent indicated yes, down 10 percentage points from the previous year. Another question asked if employees have confidence in Pichai and his management team to effectively lead Google in the future. Positive responses represented 74 percent of the total, an 18 point decline from a year earlier.”¹

In the article, there was much hand-wringing about the state of leadership at Google, given the year-over-year declines. But perhaps what is most notable is the fact that this survey exists at all. The survey is a feedback loop, one surely leveraged by Google’s CEO, board and executive team to take stock. It provides essential data from a key stakeholder group. To my way of thinking, it is evidence of a healthy governance system.

Governance system membership includes the board, the CEO and the executive team. One could argue that membership should stop at board and CEO. But a system’s boundary has integrity when a preponderance of work occurs inside its edges, pursuing a unique purpose. The governance system’s purpose is to direct and control the operation and strategic direction of the enterprise. The entire executive team is integral to the enterprise’s operation and strategic direction; as such it should be included within the governance system boundary. The governance system is a meta system. It exists to uplift the operating systems and other meta systems.

A healthy governance system is rich with feedback loops. Ecosystem to board. Board to CEO. CEO to board. Exec team to CEO. CEO to exec team, exec team to workers, workers to exec team, customers to workers…. these diverse feedback loops weave resilience into the enterprise. In the board’s relationship with the CEO and executive team it balances autonomy and alignment — just as executives do with domain teams. The effective board, it has been said, is strategically engaged and operationally distant.

To do their jobs, In The Loop board members need to understand current state and weigh in on strategic direction. They closely review reports from management. They receive and challenge strategic and financial plans. At board meetings, they seek to hear presentations not just from the CEO, but also from other members of the executive team. They attend cocktail parties that bring together board members and executive team members, where informal conversations provide subtle opportunities to better understand executive motivations and competencies.

They attend trade shows. At these, they converse with customers and prospects and visit the booths of competitors. They review social media and read business news, seeking to understand the company’s brand equity and the ecosystem context. All of these are feedback loops.

Collectively, these feedback loops prepare board members to properly execute their duties of care. The executive team will always have a deeper understanding of the enterprise than the board. It is closest to the most important challenges and opportunities. But board members need to gain the best understanding they can, within the constraints of their roles, of the enterprise’s health and position in the ecosystem. It has been said that in effective boards, board members are strategically engaged and operationally distant. Their job is to see the forest for the trees, and to impart key insights to the CEO and top team.

The executive team, of course, is operationally engaged. It understands current realities and has a sense for what is possible. The executive team often finds itself pushed by the board towards commitments that are more aggressive than it might sign up for on its own. Executive teams need to provide feedback on current state, to help shape proposed strategic direction, to be challenged, and to align with and sign onto board-approved plans.

As CEO, you are the leader of the enterprise, and the fulcrum of the governance system. As the leader of the enterprise, it is your job to chart the future. Your executive team and your board are key sources of feedback, but it’s on you to conceive of and articulate the company’s vision and strategy.

In the governance system, the CEO is like a fulcrum. Sometimes, your leverage point must move so as to increase board influence, at the cost of the executive team’s perspective — such as in accepting a board challenge to make a proposed financial plan more aggressive. At other times, your leverage point may need to slide the other way — such as when you need to hold your ground on a key hire questioned by your board, or when you face pushback on a strategic direction you determine is key to the company’s future. Most of the time, successful CEOs seek to keep the governance system in a dynamic balance, drawing upon board and executive team feedback in a continuous search for truth. Just as in physical fitness, balancing on a fulcrum strengthens your core.

The Board

Let’s start with the basics of board leadership:

- Duties

- Rules, practices and processes

- Points of impact

Duties

At minimum, a board member is required to bring proper purpose to her exercise of powers. Proper purpose requires that a board member’s discretion be unfettered — meaning that she can’t bind herself to vote in a certain way at a future board meeting, even if the motivation is pure. Conflicts of interest must be transparently exposed, and proper steps taken to avoid their impact on decisions. In situations where a conflict of interest is significant, a board member may need to recuse himself from the vote. A board must always balance the interests of shareholders, investors, management, customers, partners, government and the community.

Once the basic requirements of membership have been satisfied, board duties include:

- To develop board structure, roles and responsibilities

- To understand the scope of its authority

- To ensure advancement of the vision, mission and values of the enterprise

- To advise on and approve executive team structure, roles, responsibilities and authority

- To assess executive leadership performance and capability

- To assess collective board performance

- To advise on and approve strategy and plans

- To ensure the enterprise has the financial capacity to pursue its strategy

- To provide fiscal oversight

- To execute board decisions consistent with its authority and rules

- To ensure compliance with regulatory and accounting requirements

Rules, Practices and Processes

Rules emerge from the company’s articles of incorporation, bylaws, agreements associated with financing events, the cap table and regulatory or accounting requirements.

For public companies, rules also include regulations (such as Sarbanes Oxley) and the listing requirements of stock exchanges (such as NYSE and NASDAQ). These rules stipulate board structure, corporate reporting requirements and how different types of decisions will be made — based on the relative authority of different actors. Practices and processes are developed collaboratively by board and CEO, consistent with these rules. For a public company, certain rules are in place that guide the election of officers, rights of common shareholders, Class A vs. Class B stock, preferred share rights and so forth.

For private companies, rules are different. Financing agreements often include provisions requiring preferred shareholder approval of certain actions. Since with high growth startups management might hold a majority of total outstanding shares, such provisions ensure that management actions can be vetoed if the percentage of preferred shareholders voting for the action is insufficient.

Decisions often covered by such provisions include:

- A sale of the company

- Changes in the total number of authorized shares (either preferred or common)

- Changes to the articles of incorporation or bylaws

- The issuance of new preferred shares

- The purchase or sale of preferred or common shares

- Increasing or decreasing the size of the board

- Declaring a dividend

- Significant changes to the company’s product offerings

- Compensation changes for top management

- Incurring loans over a certain threshold

- Acquisition of another company

Boards self-organize into committees (such as an audit committee or compensation committee) to conduct certain types of work. They decide how frequently they will meet, and how a typical Board meeting agenda will flow. They stipulate the metrics they want to track. They identify who may attend a board meeting, and determine when they may want to meet in private without the CEO, to discuss her performance.

The annual strategic planning cycle is part of the governance system. While it emerges with the executive team, strategic plans are presented to the board along with the financial plan. At times this can occur over two or more board meetings as iterations are discussed and finalized.

Healthy boards also conduct self-reviews. They may even poll the CEO and executive team in a confidential survey, and openly discuss with the CEO and executive team the survey’s results.

Points of Impact

The governance system’s purpose is to direct and control. Its job is to ensure the enterprise’s generative and adaptive imperatives are being effectively pursued across time: now, near and far. Effective boards make a positive impact in eight areas:

- External context and domain expertise

- Strategy

- Financial plans

- Funding

- Connections

- Leadership competency judgments

- Company culture

- Executive team motivation and energy

The impact of governance cannot be overstated. Companies with healthy governance systems survive and thrive. Companies with dysfunctional governance systems wither and die.

The Tech Startup Board and Governance System

Over the past twelve years I have held just two jobs. For the first six years I was CEO of a VC backed tech startup. Then in 2013 I started CEO Quest, where I coach tech company CEOs. Over the past six years I have worked with many dozens of CEOs, observing their interactions with executive teams and boards. As a result I’ve gained some insight into the characteristics of a healthy tech startup board and governance system.

The Board: A Hard-to-Change, High Variation Domain

The fit systems enterprise is made up of domain teams. Domains can range from high variation (the job to be done continuously changes) to low variation (the job to be done doesn’t change much over time). Your board is the quintessential high variation domain. Its work is constantly changing. In high variation domains, complex problems require smart systems thinkers. Like other high variation domains, the goal is to maximize the density of “10Xers” on your board. Steve Blank, author of The Startup Owner’s Manual and Five Steps to the Epiphany, writes: “A veteran board can bring 50–100x more experience into a board meetingthan a first time founder.”²

In startups, most boards are comprised of investors (plus you, the CEO). Too often when raising money, CEOs focus just on economic terms. Which VC has given you the best pre-money valuation? Which VC has the least burdensome preferred share rights? The question of board member fit doesn’t even come to mind. But it’s the most important thing of all!

Effective board members bring skill and diligence to their roles, uplifting the performance of the companies they serve. The effective board draws in data from multiple feedback loops, and works hard to discern the most important things. It then works with the CEO and executive team to deepen shared understanding of current reality and top priorities. In fulfilling its advisory role, the board must:

- Understand the most critical opportunities, threats and limits to growth (from within and outside)

- Determine how to respond to emerging market factors, technologies and business models

- Strike the balance between the generative and adaptive imperatives

- Strike the balance between now, near and far

- Determine how much focus to place on securing new funding, given cash constraints

- Ascertain competency gaps in the enterprise

- Assess the CEO’s performance, and by extension, that of the top team

- Advise, not manage (avoid translating insight into micromanagement)

In an early stage startup, a board member needs to be a competent participant in helping the company scale. Let’s say you have a five person board, comprised of three investors, your co-founder and you, the founding CEO. Amongst the three investor board members, try to ensure that:

- At least one has been a founding CEO of a tech company that successfully scaled and exited

- At least one has experience in finding product / market fit

- At least one has experience in scaling a revenue engine

- At least one has experience on both sides of VC financing events

- At least one has domain expertise and is highly connected to key actors in the market you serve

It is hard to scale a company. The board of an early stage startup is likely to confront multiple crises on the journey. Every board member needs to be an activist, coaxing the company into viability. Here are some of the typical challenges boards face:

- The company is three months away from running out of cash and the CEO has failed to find new investors. Do we execute an internal financing round to keep going, or let the company fail?

- The company has hit a plateau. We’ll need to raise more money in six months, but without growth we won’t be able to raise external money. The CEO has proposed to pivot the company into a new product and business model. It will require a $2M internal financing round. Shall we support the pivot? Keep on the current path? Try to sell? Or should we shut down and sweep the bank account?

- Performance has lagged and company morale is low. Top talent is walking out the door. Do we need to replace the CEO?

Effective board members are able to see the forest for the trees, are comfortable with ambiguity and are calm in the storm. They are respected within their VC funds and can get support for a new financing round if they believe in it themselves. They focus conversations on the important things — such as proof of product / market fit and traction. They look for ways to personally contribute. They can set aside their personal investment interests and advise on behalf of the company overall. They exhibit wisdom and good judgment. They can act decisively when necessary, but prefer to advise and coach.

Choose board members wisely. You hire employees but you marry board members.

You and Your Executive Team — The Rest of the Governance System

If you’re the CEO, you must live within the boundaries of authority granted to you by the board. You balance leadership and followership. You convey the facts on the ground. You are transparent, at the right level of abstraction given the context. As events occur that might materially change the board’s key assumptions about current state, you give timely updates. You articulate the path forward via strategy and plans. But your advocacy is followed by inquiry. You genuinely want board counsel.

You understand that the board’s responsibility is to stress test your thinking and plans. Its job is to assess you and your team. No amount of preparation will free you from the stress testing and the critical assessments. They are part of the process. Time and again I have seen good teams put good plans in front of good boards. The result is always a better plan. It’s a stressful but helpful step.

From time to time, exec team members are asked to lead a board discussion. These are moments of truth for executives. The board has few opportunities to assess executives, so the smart exec will prepare well for these occasions.

Optimization vs. Maximization

The pressures of scaling at every stage make for complex decision making inside the governance system. It is easy for any actor to try to maximize her short term position. The investor wants to avoid putting in more money until the future is more clear. The executive team member wants to avoid signing on to an aggressive financial plan, so the chance for a bonus is higher. The CEO wants to avoid sharing with the board some inconvenient truths, so as to feel more secure in his position. Investors, excited by last year’s growth, want a super aggressive financial plan they can boast about to fellow VC partners.

These are maximization behaviors. In a healthy governance system, actors engage in optimization behaviors. They balance now, near and far. They balance the needs of all stakeholders. They are aggressive but realistic. They confront the inconvenient truths and make the tough decisions.

Stories: How Dysfunctional Can a Board Be?

Over the years I have seen boards make staggeringly bad decisions. I’ve seen a solid CEO facing headwinds let go, then watched as his replacement ran the business into the ground. I’ve seen an executive chairman put in place “to advise” the CEO, causing a confusion in leadership authority that undercut the CEO. I’ve seen a necessary pivot resisted because its new business model is inconsistent with the investor’s original investment thesis.

Board decisions such as these are all too common.

For some boards it’s worse. They have degenerated into perpetual dysfunction, incapable of making sound decisions. In the worst examples, board members act solely on selfish interest; they have lost the ability to seek the greater good. A single board member might block a critical funding round or derail a planned sale. The latter happened in one situation I know well, costing the company its only chance at an exit. Six years later it remains a zombie, making just enough money to survive while being too unattractive to sell.

But no story of board dysfunction can beat the story of Hewlett Packard.

In January 2005, HP’s board forced Carly Fiorina to resign her role as chairman and CEO. She had overseen the disastrous merger of HP and Compaq; the result had been a divided culture and a company adrift.

Mark Hurd was named the new CEO. He was appointed to the HP board, but was not initially named board chairman. Around the time of Hurd’s hiring, the business press buzzed with rumors of conflict within the HP board about the future direction of the company. The chairman at the time, Patricia Dunn, went so far as to mobilize an investigation into press leaks. She hired a private investigator to entrap board members by assuming false identities through “pretexting”. The goal was to reveal who the leaker was.

Dunn resigned in humiliation after her ruse was discovered. Hurd went on to set things right at HP. He cut costs while building competitive business units. Under his leadership HP became the leader in desktop and laptop computer sales. The market share of the printers business unit approached fifty percent. He beat Wall Street expectations in twenty-one out of twenty two quarters. Revenue rose sixty three percent, and the stock price doubled.

Despite that success, the board continued to thrash around in open conflict. In 2010, when a charge came forward that Hurd had engaged in an inappropriate relationship with an employee, the board initiated an investigation. The two board members assigned to conduct the investigation found no evidence of sexual harassment, but did discover a few thousand dollars of expense reporting irregularities. For context, the previous year Mark Hurd’s compensation had been $24M. These two board members pressed for Hurd to be dismissed due to a violation of the HP employee code of ethics. Others on the board were astounded that termination was on the table and fiercely resisted it. Despite these protestations, in August 2010 Mark Hurd resigned under pressure.

Because Hurd had been terminated without a replacement, the board was forced to conduct an accelerated CEO search. Many qualified candidates declined interest, concerned about board dysfunction. When the search committee of the board settled on Leo Apotheker, a little known European executive from SAP, most board members didn’t even meet with him. Shockingly, sight unseen, the board voted him into the CEO role.

Apotheker then went on to make a series of ill-fated decisions. He discontinued the webOS device business. He bought the British company Autonomy for $11B, only to write it down by $8.8B less than a year later. He announced plans to divest the PC division. During Apotheker’s tenure HP stock dropped forty percent. Eleven months after his hiring, he was terminated by the same board that had so briskly and blithely hired him.

In a New York Times article published at the time, former HP director and Silicon Valley legend Tom Perkins said, “It’s got to be the worst board in the history of business.”³

A governance system’s health starts with the board. A bad board trumps a strong CEO and executive team every day of the week. Do everything you can do to build a solid board. It’s the single most important step in creating a healthy governance system.

To view all chapters go here.

If you would like more CEO insights into scaling your revenue engine and building a high-growth tech company, please visit us at CEOQuest.com, and follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter, and YouTube.

Notes

- Huet, Ellen, and Bergen, Mark. “More Google Employees Are Losing Faith in Their CEO’s Vision”. Bloomberg.com, February 1, 2019.

- Blank, Steve. “What’s Wrong with Board Meetings”. FastCompany.com, June 2011. https://www.fastcompany.com/1756758/whats-wrong-board-meetings

- Stewart, James B. “Voting to Hire a Chief Without Meeting Him”. The New York Times, September 21, 2011. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/22/business/voting-to-hire-a-chief-without-meeting-him.html.